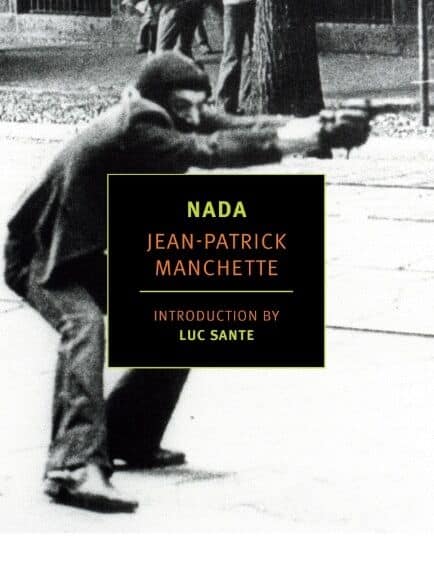

The cheapest type of movie you can make is a movie that takes place on paper – that is, a novel. Cinema and prose fiction are different art forms with different strengths, but don’t tell that to Jean-Patrick Manchette (1942-1995), the French crime novelist whose 1972 literary sensation Nada recently appeared in English for the first time, thanks to New York Review Books Classics, which previously published three of his other works.

Nada reads like a Jean-Pierre Melville screenplay with a political twist. Manchette’s career in fiction – which led him to a career in screenwriting – began in the years after the civil unrest of May 1968 in Paris, and as a former activist, he incorporated the revolutionary fervor of his era into the typically fatalistic genre of the hard boiled thriller. Nada tells the story of a gang of anarchists who set out to kidnap the American ambassador in Paris.

The author invokes a certain structural fatalism of his own: he lets us know from page one that the police have won and the anarchists have lost. We can only stick around to find out how the plot went wrong.

Readers may associate NYRB Classics with highbrow obscurities from the world of international belles-lettres – even an earlier foray into 20th-century francophone pulp, in a pair of republished novels by Georges Simenon, turned up works of serious psychological inquiry – but Nada is fully a product of commercial art: short and fast with flat characters and plenty of action. Manchette stages his scenes – in cafes, in shabby apartments, and finally in a country hideaway–in the fashion of a workmanlike cinematographer, hoping to convey the events of the story as clearly and quickly as possible.

Inspired by the stylish terseness of Dashiell Hammett, Manchette’s prose, as translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith, is primarily informational – as when, amid the pain of a character stung by tear gas, the narration nonetheless finds time to identify the weapon, for the reader, as “a green and white cloud of chlorobenzalmalononitrile, also known as CS gas.” But the writing perks up in moments of more gruesome violence, like the aftermath of a shotgun blast: “Fragments of bone and brains and tufts of hair hurtled through the air like the grand finale of a fireworks display,” Manchette rhapsodizes (sorry for the image).

Why do the anarchists want to kidnap the U.S. Ambassador to France, specifically? We don’t know. As in Bertrand Bonello’s Nocturama, we see the planning of the crime from the outside looking in, with a limited frame of reference. The people responsible have names, but Manchette prefers to describe them by shorthand: the Catalan, the alcoholic, and so on.

The ideal reader of Nada arrives with a detailed knowledge of French left politics: the difference, for example, between the FTP (Francs-Tireurs et Partisans) and the PSU (Parti Socialiste Unifié). I’m not that reader, but the most striking aspect of the novel remains its suggestion of the intensity of France’s political culture in the early ‘70s. It’s in the rabble-rousing graffiti that Manchette observes, in the fictional riots that he reports, and in his conversations where self-identified libertarian communists scornfully accuse one another of succumbing to Marxism or Maoism. There are even squabbling partisan factions within French law enforcement, which pursues our protagonists in a spirit of unceasing recklessness, brutality, and stupidity.

Most of all, one gets a sense of the climate from the sheer number of political actors that populate Nada’s periphery: the author notes that Le Monde’s article about the kidnapping, within the universe of the novel, includes “a special sidebar for the points of view of fifteen leftist groups.” I’m a leftist, and I can’t name 15 leftist groups in the whole United States.

In Nada, Manchette never tries to articulate the substance of his own leftism, either implicitly (through story) or explicitly (by editorializing). Even so, he captured the interest of like-minded readers who craved stories about radicals: representation is so important, as the kids now say. “Manchette essentially launched an industry of left-wing thrillers, ranging from a historically minded stylist such as Daeninckx to the brew of crime, porn, and agitprop served up by Editions de la Brigandine in their quickies,” according to Luc Sante’s introduction in the NYRB Classics edition.

No such industry has ever existed in the United States, where, if a reader wants a thriller with apolitical backdrop, they have no choice but to hear about the brave exploits of an FBI or CIA agent–or perhaps about the heroic escape of a kidnapped American diplomat (from the diplomat’s point of view). This is the culture that made a hero of Robert Mueller.

Which is not to say that the anarchists of Nada are heroes, either. Too late, Manchette’s creations realize (out of nowhere – character development isn’t his strong suit) that terrorism principally serves to legitimate the authoritarianism of the state: it must only ever be a last resort. Naturally, this lesson – a dialing-back of the characters’ earlier position – is unimaginable as the conservative moral of an American story.