When everyone is making it up on the spot, who’s the composer? This is a question every time an album track has a composer credit, or when a musician on the bandstand announces that “this was written/composed by” so-and-so.

If you listen to jazz at all, you’ve heard one or more musicians play a tune (usually a song form of some kind, whether it’s 12-bar blues or something from George Gershwin), improvise based on the form of that tune, then bring it all back home by repeating the original material (getting back to the “head”). Or you’ve heard a record where the musicians play an entirely free improvisation, music making preserved because it’s captured on tape or hard drive and given a composer credit even though it’s something that can never be repeated, only reproduced by playing the recording.

In between are figures like Cecil Taylor and Butch Morris who, when working with other musicians, used some combination of musical material and guidance, the musicians improvising in an aesthetic direction shaped by the leader. Who’s the composer there?

The question matters in the most basic material sense because the composer gets the copyright and the fees. But sticking only with the art, it matters because jazz has a unique relationship with the idea of the composer, and that relationship can be ambiguous.

In practice, composing has a lot to do with documentation, setting an idea in an at least semi-permanent format so that it can be shared far and wide. Notating music on paper means that composer and performer can connect across time and space without ever meeting – that’s what happens every time a pianist plays a Beethoven sonata. There’s a document there, a record, a way to transmit information from one point to the next, from past to present to future.

Here in the west, we love documentation; we need it to cement something as real and reliable. It’s all pictures-or-gtfoh, or replay confirming officially that guy scored the touchdown which we all saw him do in real time, or historians not believing Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemmings had children because gosh darn it Jefferson didn’t write down how many kids he begat via his slave mistress so watchagonnado? Reality in America isn’t real until it can be replayed on video, or mirrored by an official document (maybe a longform birth certificate?).

The Hemmings/Jefferson case is an egregious and acutely relevant example of why documentation matters even if it can’t show, or even obscures, the truth – some “truths” are in the hands of de facto and de jure institutions. Jazz is an oral tradition, which is what music was for 50,000 years, globally, until the symbolic language of music rotation, and printing, developed in the west. The history of documents in music is barely a sliver on that timeline, yet the document, rather than the music itself, has come to be the thing that matters.

Since Beethoven, the primary figure in art music has been the composer. In jazz, it’s been the musician, the soloist and improviser. This is the document/oral tradition divide. There have been extraordinary composers in jazz, Duke Ellington of course but also Jelly Roll Morton, Thelonious Monk, and Charles Mingus. But for decades they weren’t seen as legit, somehow not doing the notes-on-paper thing in the right way. Even Gershwin, like Ellington an extraordinary composer who was essential to the sound of jazz, was not seen as a legitimate classical composer, because classical music wasn’t supposed to be bluesy or swinging or sexy.

There were issues of social status and prestige involved when the Third Stream movement started in the late ’40s and early ’50s, people like John Lewis and Stan Kenton and Gunther Schuller trying to achieve “legit” status by using classical compositional techniques like counterpoint and fugal structures. A lot of this music is awkward, worst of all when it uses Schoenberg’s atonal 12-tone method – history has shown this to be an oddity and a dead end, but for many years the classical establishment saw atonality as the only acceptable practice, and so composers thought they had to write music like that in order to be taken seriously. Unfortunately some still do.

The earth is round but the cultural world is flat. High culture, low culture, and in between are distinctions that have nothing to do with content and everything to do with the social status and attitudes of consumers – Mozart, who wrote some intentionally vulgar music, and Gershwin aren’t low because the people who listen to them think themselves high. They are high because their music is wonderful.

Mozart wrote sonatas, Ellington wrote songs. And as I bring up at every opportunity, it’s harder to write a song than a sonata; the latter has fairly specific structural guidelines in which a composer can fit just about anything, while the former must be an impeccable and memorable three-minute encapsulation of mood, outlook, values, and personal history. A sonata is an abstract idea that can be admired for its architecture, a song has to work, it has to tell you something, it has to mean something. And if it’s a song without words, like Ellington’s “Johnny Come Lately” or “Black and Tan Fantasy” or “The Mooche,” it takes mastery to make it work.

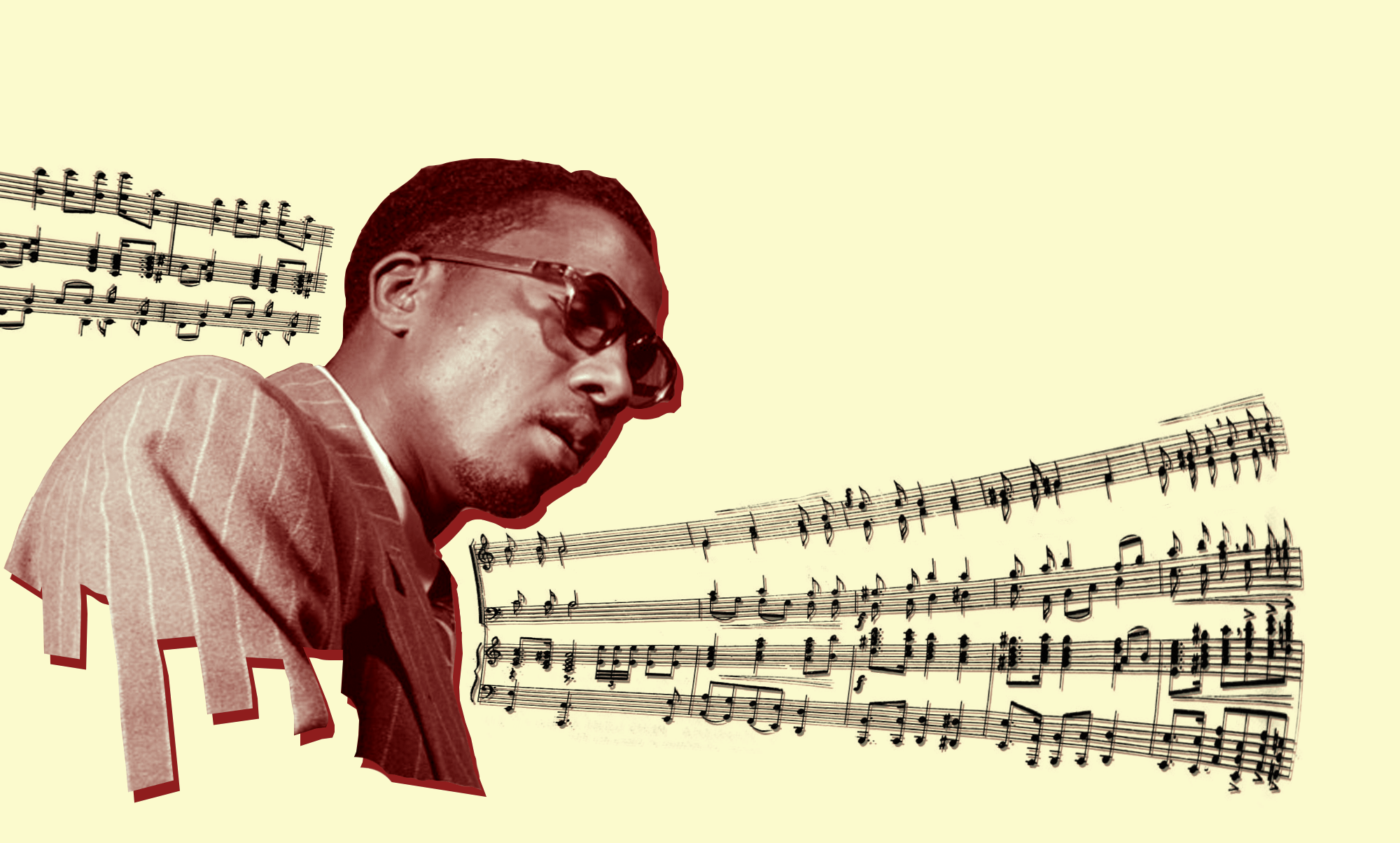

This is all to say that Beethoven’s “Moonlight” Sonata is no higher than Monk’s “‘Round Midnight,” nor is Monk any less a composer. In terms of composing – writing it all out – in the jazz idiom, Monk is one of the greats. And not just a great jazz composer, a great composer.

Monk, in fact, is better seen not in the context of jazz, but in relation to Igor Stravinsky. Their methods were near identical, take a small unit of music like a phrase or a rhythm, and repeat it while opening up fascination by shifting around the pulse and accented downbeats. For the both of them, that produced music with a great physical feeling and perpetual momentum. If anything, Monk might have been even better at this, because since he was working in song form, he had to encapsulate his ideas with greater brevity and stronger logic.

Monk’s example shows that jazz composing can be great composing while never having to bother with appeasing classical convention. Mingus did the same with a different style. He fiddled around with some Third Stream notions – notably with composer and saxophonist Teo Macero, who went on to produce albums like Bitches Brew with Miles Davis, which is a whole other story of composition in the 20th century – but found his genius working with a mix of blues, swing, and hard bop structured into extended, discontinuous forms. “Fables of Faubus” is the great example, the type of piece that takes abstract skill to keep together, and is not only jazz, but reaches all the way back to Jelly Roll Morton for it flavors.

A great jazz composer is a great composer, period. You don’t have to write fourth species Baroque counterpoint like Bach to write great counterpoint, which is what Henry Threadgill is doing with his system that organizes his pieces around intervals that shift their relative positions in the ensemble, while the distances themselves stay constant. You can work with electronics and shards of musical ideas, like composer Steve Lampert does – Lampert’s ideas are ecumenical, but they make great material for jazz musicians like Noah Preminger, who digs deep into them on his recent album Zigsaw: Music of Steve Lampert. Avant-garde superstar John Zorn has, through dedicated work, become an exceptional composer of dense, neo-romantic modern music, including a wise technique where he writes out the part for one instrument and has other musicians improvise around it in that context. For something more conventional, but no less brilliant or important, there is big band leader Darcy James Argue, who crafts great, extended scores that utilize all sorts of ideas about harmony, rhythm, and form – not to mention drama and multi-media narrative – adapted from modern classical music, and it’s all nothing but jazz.

Recommended listening:

- Duke Ellington, Never No Lament: The Blanton-Webster Band

- Duke Ellington, Early Ellington: The Original Decca Recordings

- George Gershwin, Michael Tilson Thomas Conducts Gershwin

- Darcy James Argue’s Secret Society, Infernal Machines

- Darcy James Argue’s Secret Society, Real Enemies

- Noah Preminger, Zigsaw: The Music of Steve Lampert

- Charles Mingus, Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus

- Charles Mingus, Oh Yeah

- Thelonious Monk, Genius Of Modern Music, Volumes 1 & 2

- Butch Morris, Dust to Dust

- Henry Threadgill, Easily Slip Into Another World

- Henry Threadgill, In For a Penny, In For a Pound (2016 Pulitzer Prize in Music)

- John Zorn, The Big Gundown

- John Zorn, Rimbaud.

Author

-

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/

View all posts

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/