Last night I attended what was billed as the first in a series of “Public Planning Meetings for the Long Island College Hospital Site (LICH).” The meeting was a co-production of the Cobble Hill Association (CHA) , local elected officials, and FORTIS, the real estate development company chosen by NY State to redevelop the former LICH properties.

The meeting was held in a large room at the Brooklyn Montessori School, at Bergen and Court. It was standing room only by the time I got there, a little after 7 pm. I saw some people I knew, mostly elected officials and their staffs, including Eric Adams and Diana Reyna (the Borough President’s deputy), Jo Anne Simon, Steve Levin and Daniel Squadron.

The most important politician in the room was Brad Lander. Brad represents Cobble Hill in the NY City Council. He will ultimately be either a community hero or the fall guy in this battle. Brad is highly intelligent, has worked his way up to the number two position in the city council, and presides over a district that includes both the Gowanus and Cobble Hill – two areas with tremendous land use issues. Lander himself comes from a background of affordable housing, beginning his career at the Fifth Avenue Committee, a community development corporation. He is hedging his bets, agreeing with the Cobble Hill audience that they are in a horrible situation, yet at the same time urging the zoning change process (ULURP) sought by FORTIS, calling it the best of a bad situation.

I watched an audience of Cobble Hill homeowners who for the most part sat patiently, listening as the FORTIS architect presented plans for the transformation of the hospital grounds into residential skyscrapers. Dan Kaplan, a senior partner at FXFOWLE, the company chosen to design their LICH project, methodically went through a slideshow similar to the iconoclastic presentation he made last May at a previous CHA meeting – one which stunned the Cobble Hill community as they had no real idea of what they were in for.

This time, having foreknowledge, most everyone sat resignedly, listening as details about square footage and redesigning open space were patiently explained by the grandmotherly Mr. Kaplan, who almost sounded like one of the resigned, local homeowners as he went through his required drill. One might even confuse him for a concerned resident, he seemed to understand both sides – but architects, like lawyers, usually will work for whoever pays, so he dutifully obeyed his paymaster.

You will probably read in other local media about the rest of the meeting, quiet statements from the Cobble Hill Association, pleadings about the need to achieve consensus from the councilman, and some audience participation, in the form of questions, with little anger or passion evident, save from one woman in red.

The Landmarks question

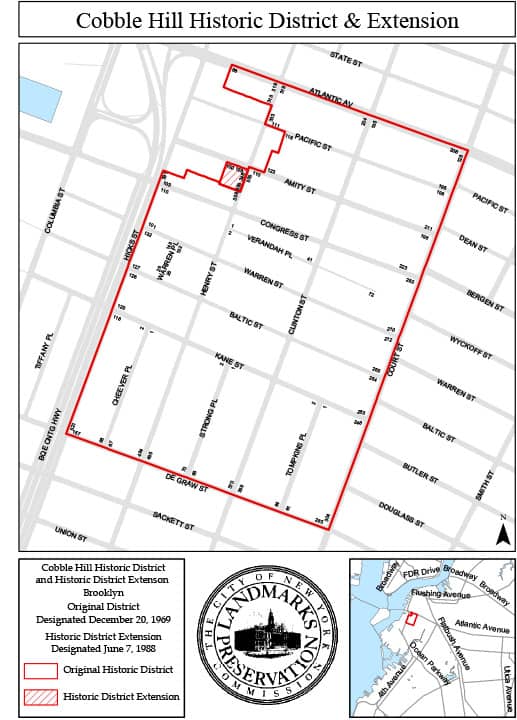

What has been front and center for me – ever since the May meeting – are questions surrounding Cobble Hill’s designation as an Historic District. Roy Sloane, current CHA president, brought this up. He pointed out that the development plan takes advantage of the flexibility offered the hospital by the community – keeping their footprint out of the historic district to allow them to grow as needed. This altruism is now turned around to attack the community.

This newspaper covered the LICH’s demise for two years. We went to protests, we interviewed community and union leaders, and we spoke to doctors, lawyers and politicians to try and convey the story.

The part of the story that we neglected to tell was what could come after. Perhaps we never believed the hospital would really be shut down.

Maybe if more Cobble Hill residents had an inkling about the prospect of skyscrapers and density, more would have come to the protests. Maybe then the media would have paid more attention to the battle – putting more pressure on Albany to preserve the hospital. But nobody talked about skyscrapers. Most of the rallies were organized by the nurse’s union, and their goal was to preserve jobs, not buildings.

Landmarks law came relatively late to NYC. The Landmarks Commission was established in 1965, spurred on by the destruction of the historic Pennsylvania Station (opposite the 34th Street Morgan Post Office). Their first task was a three year study to designate certain neighborhoods as deserving a historical designation. Cobble Hill was one of the first neighborhoods considered and chosen.

It is pretty easy to find the original report that named Cobble Hill a Historic District. It is a 75 page, typewritten document. It pretty much gives the history of every building in the neighborhood – block by block. It also speaks about the community as a whole:

“Designation of the Cobble Hill Historic District will strengthen the aims of the community by tending to prevent the needless loss of architectural quality by attrition and by controlling future alterations and construction. Designation is a major step to ensure protection and enhancement of the quality and character of the entire neighborhood.”

and

“The fact that apartment houses did not invade the streets in recent years is responsible for the charming, low lying quality of this neighborhood where the skyline is punctuated occasionally only by church spires.”

The original reported, issued December 30, 1969, explains that the designation was strongly encouraged by the Cobble Hill community, and its representative, the Cobble Hill Association. It notes that representatives from Long Island College Hospital attended public hearings to oppose the designation. They, along with a few churches, were the only ones opposing the limits that landmarking would impose. The neighborhood agreed, and left LICH out of the district.

Spirit vs letter

When you google “spirit of the law,” you get this from Wikipedia:

“The letter of the law versus the spirit of the law is an idiomatic antithesis. When one obeys the letter of the law but not the spirit, one is obeying the literal interpretation of the words (the “letter”) of the law, but not necessarily the intent of those who wrote the law. Conversely, when one obeys the spirit of the law but not the letter, one is doing what the authors of the law intended, though not necessarily adhering to the literal wording.”

Based upon an understanding of the intent of the Landmarks Preservation Commission as indicated by the above quotes regarding preservation in Cobble Hill, it is hard to imagine that skyscrapers in or adjacent to the historic district is something they would approve of. Had they imagined, back in 1969, that the hospital would one day be shut, one might strongly believe that they would have imposed restrictions on what could replace it.

They do, in fact, speak of inappropriate development in describing a block nearby the hospital:

“Hicks Street between Degraw and Kane – This is a street of multiple uses such as is often found on the edges of Historic Districts. Near the center of the street a five-story parochial school, built in 1922, rises above its three and four-story older neighbors. In the event of re-development a block front such as this should properly be under architectural controls because it relates so critically to its surroundings. The rest of this block has many charming houses with original ironwork (facing Kane Street and Cheever Place). An inappropriate development of the Hicks Street frontage could be a serious intrusion into the monogenous character of the Historic District.” (boldness added by RHSR for emphasis).

Mention need also be made of the residents of Cobble Hill, many of them who have paid a handsome price for the privilege of living in a landmarked community. They spent their money on their home with the understanding that their community would not be adding huge batches of new families, nor large skyscrapers, and probably not the chain stores that the FORTIS plan would inevitably attract. The State of NY fails the trust of its citizens by exploiting the landmarks loophole.

It seems to me that pushing the neighborhood into a compromise zoning change is not serving the interests of fairness.

Had the Cobble Hill neighborhood never been designated a historic district, there would be no case. But it has been for over forty years, and in the spirit of landmarks law one must believe that there was never any intent for skyscrapers invading this historic neighborhood.

One Comment

Where profits alone count, there can be no thinking about the rhythms of nature, its phases of decay and regeneration, or the complexity of ecosystems which may be gravely upset by human intervention…. It is not enough to balance, in the medium term, the protection of nature with financial gain, or the preservation of the environment with progress.

– Pope Francis, Papal Encyclical “Laudato Si,” June 18, 2015

Make no mistake about it, there is absolutely no philanthropy behind any of the developer give-backs being dangled before the community. The community will have to pay-and-pay in so many ways, while the developer calculates the optimum FAR/density to cover expenses and insure high profits– profits at levels which make billionaires who then buy the presidency.