No plan survives contact with reality. At the start of this summer, energized by recent listening, I started to dig into my library of books on free jazz, titles like Val Wilmer’s As Serious As Your LIfe, Freedom Is, Freedom Ain’t by Scott Saul, Michael Heller’s Loft Jazz, and Ekkehard Jost’s im-portant study, Free Jazz. I was jazzed.

But then Bloomsbury put out a new batch of 33-1/3 books, including Computerworld by Ste-ve Tupai Francis, a book on one of my all-time favorite albums by one of the most important bands ever in the history of popular music, and I got sidetracked by the seductive sonic utopias of Kraft-werk, and began reading all the books there are on them.

Somehow, though, Greil Marcus drew my attention away from all that. I don’t remember how that happened, I think I was browsing one weekend afternoon at Freebird Books on Columbia Steet, and The Old, Weird America caught my eye. So I dipped back in to Lipstick Traces, sampled a couple of his collections, and started reading his book on The Doors. That’s when something that had been dormant in my thinking resurfaced, the connection through process of experience and production: take things in things, make them part of one’s personal existence, and then mine that as material for words and sounds and images and movement. It was The Doors book that did it. I don’t particularly enjoy that band; Jim Morrison’s expressive charisma was very real, but musically they often seem to be casting about for an identity to put on and don’t have the musical chops to con-vincingly handle the blues, jazzy rock, stage music, Beetles-like baroque touches. Their big hits like “Light My Fire” are rhythmically awkward, they phase the blues and Kurt Weil all wrong, it’s very white, very clunky, very suburban. “The End” is what works for me, the moment when they shed everything else and realize that they are a psychedelic stoner band with a substantial appreciation for beautiful inner worlds.

That’s not the point though. Rather, it’s that Marcus’ book is so interesting because his experi-ence draws together listening to the band with seeing movies, reading Leslie Fiedler, remembering family moments. An older literary anthology is titled The Critic As Artist (after the Oscar Wilde es-say), and Marcus is a real artist, responding to stimulus, taking in experience, and making some-thing new through criticism.

What this has to do with jazz is an extension of what I discussed in last month’s column, which was the effect of professional music schooling on jazz, how the music has been losing variety in the mainstream and how that makes the margins, music that can’t be folded into an institutional setting, more vital than ever. Institutions develop a consensus about what they value, and joining that insti-tution means accepting those values. In the political economy of non-commercial music in America, institutions that succeed are the ones that best raise money. And funding in America rewards suc-cess, regardless of quality or need (this is why the Metropolitan Opera regularly gets more grant money than any other music organization in New York City, and venues at the margins regularly vanish). Nothing breeds imitation like success, so other institutions follow the same consensus that hauls in the most money.

What we end up with—in a culture where there’s a credentialism arms race fueled by another consensus that an advanced degree is necessary for every “professional” endeavor, which in turn has engorged the administrative budgets of universities as they chase more students who they sad-dle with ruinous debt that only the jobs that damage society, like investment banker, contracts law-yer, and management consultant, can ever satisfy—is the consensus that what makes a jazz musi-cian is a certain set of rhythmic ideas and harmonic knowledge, scales and the Great American Songbook, and so a huge amount of new jazz that comes out expresses that consensus, and the margin get pushed away.

That consensus in and of itself is not a bad thing, and in fact it’s useful. Jazz is too young to yet be fully defined, and so shifting ideas add to the pot of what the music might be. Shifting, complex meters and a post-Micheal Brecker harmonic sense, straight eighth notes and funk pulses often sound great. But when that’s most of what’s played, that’s homogeneity and not healthy for the music. Looking at the past, the movement from traditional jazz to swing to bebop to cool to hard bop to modal and beyond, massive revolutions in the idea of just what was possible in jazz, all hap-pened in a 40 year span—and this without the fuel of the internet’s antiphonal immediacy. Yet one huge, deleterious effect of the internet is that it actually produces stagnation, as influencers of all sorts chase the same thing, then each other. The stagnation in jazz is smilier to the stagnation in in-die-classical music, and that is a manifestation of people seeking the safety in numbers that protects from criticism and failure.

Failure, my friends, is where it’s at. Failure is a success in and of itself because it creates inval-uable lessons and creates accidents that contain revelatons. Failure, failing better, is an ethos, and that ethos connects across the simple act of making jazz to literature and poetry, fine arts, and more. The most interesting music in jazz is, still, being made by artists who are musicians but who come at their work from other contexts and ideas, including Tyshawn Sorey and his post-Morton Feld-man composing, Jason Moran and his attempts to capture aesthetic and social history in music, Henry Threadgill and his continuing reinvention of contrapuntal systems.

These artists succeed because they are willing to fail. Not every Sorey composition has fully worked, but each has brought him to new classical and jazz ideas. Moran can fall in love with his subjects and treat them too kindly, when he’s at his best taking things apart and reassembling them. Threadgill’s latest album, Poof (Pi Recordings) is fine but nowhere near his best, but it seems to consolidate past ideas and set new transitions in motion—that’s invaluable.

Meanwhile, Brad Mehldau has been overdoing his mainstream success to the point of putting out his appalling take on prog-rock, Jacob’s Ladder (Nonesuch), a perfect example of safety and self-satisfaction leading to nihilism. And dozens of other musician put out albums that are polished like a telescope’s mirror and vanish into the air like a breeze.

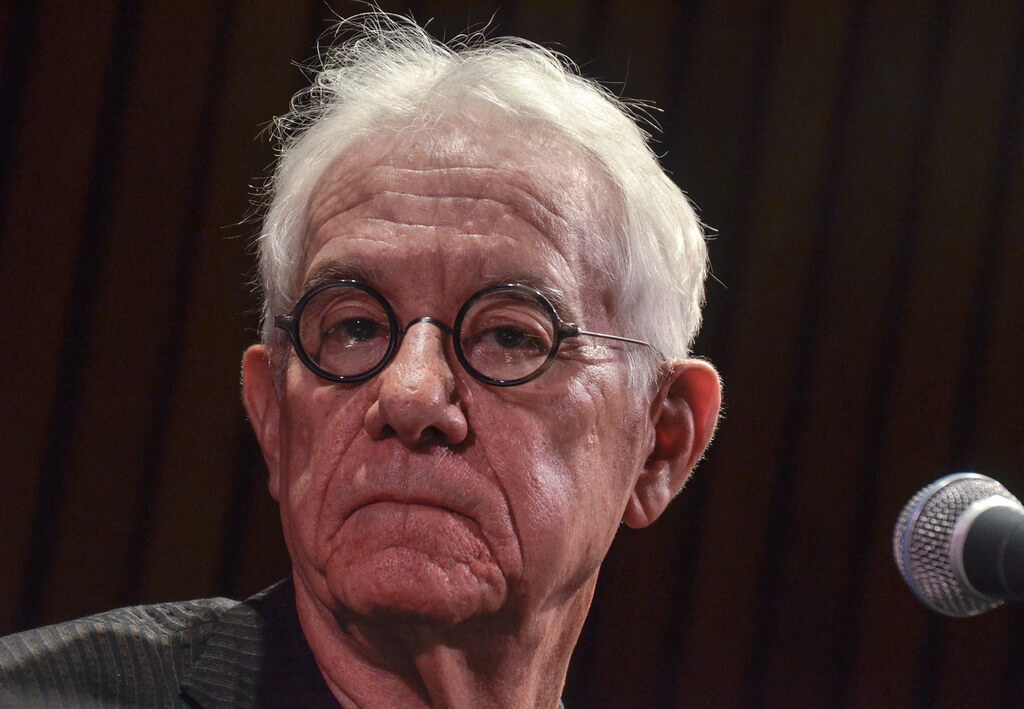

And here’s where I get back to Greil Marcus. The “Top 10” lists he put together for decades are great. That’s usually the laziest kind of writing, but in his hands he brings together the mun-dane, the profound, and the awful. The lists include music, of course, but also books, commercial jingles, flyers for punk shows, even the notice of the discover of the few existing photographs of Robert Johnson—anything that had an effect on him. He chronicles success and failures, the latter often more interesting. But the main thing is that it’s more than music, it’s a critical mind at work, experienced but also capricious, taking things in. Marcus has his values, but no consensus, because that’s both a project and a process, and one that no individual artist should ever think is complete.

Author

-

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/

View all posts

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/