A year after Hurricane Sandy, a Columbia University graduate student named Shannon Geiss came to Red Hook to record conversations with neighborhood residents for her thesis project, “Ambiguous Borders: Defining Community in Red Hook, Brooklyn,” an audio walking tour that would earn her a master’s degree in oral history in 2014. Her work found its final interview subject in a 19-year-old, Rasheed Johnson, who had moved to the Red Hook Houses eight years earlier.

“Are there any things that have changed since you’ve been here?” Gneiss asks.

Johnson’s tone is melancholy. “Just hangout spots, basically. Like I told you, my favorite spot when I was younger was the graffiti spot by IKEA. IKEA moved there, tore down the whole graffiti spot. The only hangout spot that’s actually left is the pier, is Valentino Pier, and I don’t think they knocking that down any time soon.”

Gneiss presses further: “I’m wondering about – I don’t know how to put this. Do you spend very much time over on Van Brunt Street, or are there are certain parts of the neighborhood that you spend more time in?”

“Now, I spend more time at home than anywhere else,” Johnson says. “If I were to go outside, I’d walk straight to Valentino Pier because that’s the only thing left of what I came to Red Hook with. I have a spot on Valentino Pier – it’s where you see the Red Hook blocks. I’ll go right across there and sit right on those rocks and just watch the waves. That’s the only thing I’ll do.”

At the time of the interview, Johnson worked as an assistant to the executive coordinator at the Red Hook Initiative, the local community center, social services provider, and youth empowerment organization at 767 Hicks Street. Gneiss notes that Johnson was “proud of his job. For Rasheed, whose apartment was without power for at least a month after the storm, it was one of the only things that kept him going. Red Hook Initiative got him through the struggles of Hurricane Sandy and has continued to inspire him to do whatever he wants with his life.”

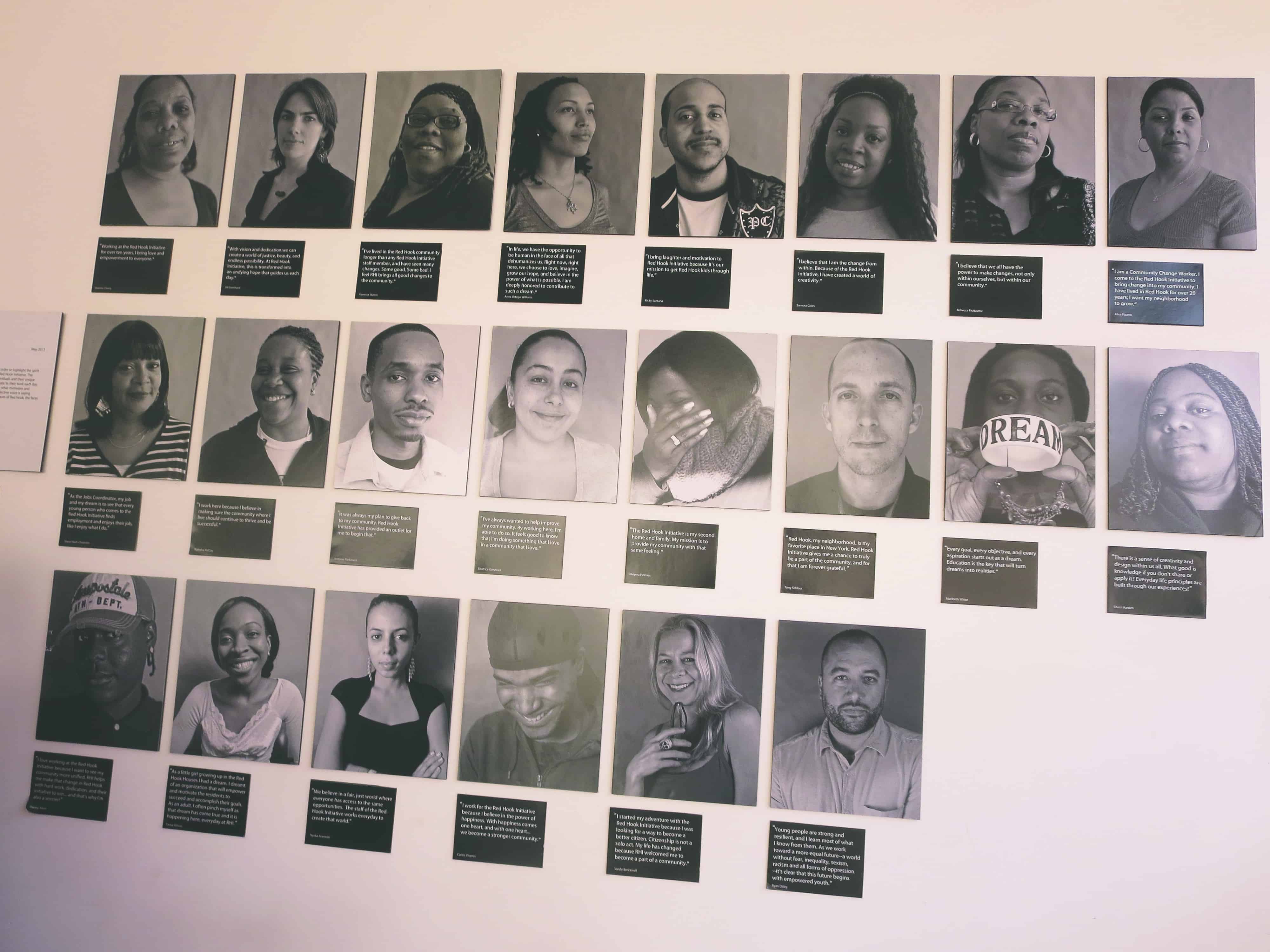

Founded in 2002, the Red Hook Initiative offers a wealth of after-school programming and community building endeavors for youth between the ages of 12 and 24. From homework help and photography classes to mental health screenings and vocational training, RHI’s programs, organized primarily within a three-phased pipeline that takes kids from middle school to college (with additional classes and events for their elders), touch more than 5,000 Red Hook residents annually by the organization’s own calculation. And because of its commitment to community hiring, residents – who account for 93 percent of the staff – also lead many of the activities.

In a neighborhood whose unemployment rate doubles that of Brooklyn at large, RHI has, over the past year alone, paid over $1.26 million in wages, stipends, and contracts to the people of Red Hook, including teenagers, whom RHI seeks to position as “co-creators of their lives, community and society,” and of RHI itself. In a 2016 interview at TechCrunch, RHI executive director Jill Eisenhard described the philosophy behind her nonprofit when she stated that “it is the people who live in a community who can create the change that is necessary for that community.”

This notion that, with the right attitude and methodology, it’s possible for a well-funded, professionalized 501(c)(3) to bypass the paternalism that can plague well-meaning nonprofits whose broad objectives and day-to-day procedures are determined outside the populations they serve has consistently guided RHI’s self-presentation and, by most accounts, has deeply informed the nature of its outreach. The role of RHI, as it conceives of itself, is not merely to treat a predetermined set of social ills but to create a safe, welcoming space for the creativity and open-ended growth of young people, who, with the help of instructors, social workers, and their own neighbors, may, for example, design workshops on topics like sexual health or dating violence and present them to their peers, or decide on their own that they would like to plant more trees in their neighborhood, with RHI providing the means for them to do so. According to Dr. Anna Ortega-Williams, a professor of social work at Hunter College who previously worked at RHI for 14 years, the organization has made its “deepest impact” by offering “unconditional love. That’s not something that’s written into a grant. It’s part of everything; it’s atmospheric. Love is atmospheric at RHI.”

Even so, the fact remains that Red Hook did not create the Red Hook Initiative. The bulk of its funding does not come from Red Hook. Its board of directors, which contains no Red Hook natives, resembles that of any flashy, well-connected New York City nonprofit, with the usual roll of app developers, film producers, magazine editors, political strategists, financial analysts, and people whose names, when Googled, yield Vogue articles about their storybook weddings in 12th-century French castles. Taken literally, Eisenhard’s statement that “it is the people who live in a community who can create the change that is necessary for that community” produces an obvious question: why, then, does the Red Hook Initiative exist?

An easy way to answer this somewhat abstract query would be to remove it from the realm of abstraction, by simply pointing to the countless lives that RHI has improved by setting up shop adjacent to the second-largest New York City Housing Authority complex, where public services are lacking and opportunities hard to find. Young people in the area can tell important stories attesting to the quality of their personal experiences at RHI. But over the course of its 16 years in Red Hook, RHI has also become bound up in a larger story of a neighborhood marked by the large-scale destruction wreaked by a natural disaster, the acceleration of gentrification, and the decline of an increasingly mismanaged and scandal-plagued NYCHA, whose arguably criminal failures under Trump’s defunded HUD to meet the basic needs of its tenants have by now fully undermined its longstanding reputation as America’s most successful big-city housing authority. In Red Hook, most people would say that, since 2002, some things have changed a lot, and other things haven’t changed at all. It’s in the context of the community’s wider history, and of the prospective futures and non-futures that seem to issue from it, that an inquiry into the nature of the Red Hook Initiative and what it aims to build begins to make sense.

Charity Navigator, a website that evaluates the efficiency and transparency of nonprofits, rates RHI four stars out of four. Locally, its reputation is just as strong. Each year, nearly every restaurant in Red Hook jumps at the chance to help volunteer-cater its annual fundraiser, Taste of Red Hook. Pierre Alexandre, co-owner of Dolce Brooklyn, called the organization’s work “amazing” and “very helpful,” and Jo Goldfarb, the director of communications at the private school Basis Independent Brooklyn, affirmed that RHI “has spearheaded meaningful, needed programs for the youth of the neighborhood.”

Judith Dailey, a retiree who operated a play therapy program at P.S. 27 until 2008, recalled that children under her care regarded RHI as a “place where they could go and talk about anything and everything.” Today, “they’re doing the same self-esteem building, the same motivation, so it’s continued, and it’s really helped a lot of young people,” she observed. “And many of the children that have gone to Red Hook Initiative have gone on to college, and they come back and pay it forward.” She identified her own granddaughter, now a college student, as one of the beneficiaries.

Raised in the Red Hook Houses, Tedron Cuevas came to RHI in 2009. “I was 15, and I wanted to maybe start working, and I was getting my thoughts together to get a job, and the Red Hook Initiative had this program called the Youth Leaders,” he recounted. “Over time, after I did the Youth Leader program, I just fell in love with the rest of the programs that was there.”

While the Youth Leaders gave Cuevas “job readiness skills” (and a reasonable stipend) and helped him get his “résumé started,” the Peer Counselors had a more profound effect. At the start of the program, “we sat down for about six hours, and we talked about peer counseling, the everyday problems that our peers go through, how it affects us, how it affects them, how does it affect their family, how does it affect their future, and how we can help.” Learning how to talk about these problems, “instead of just cursing at each other and throwing foul language at each other,” was “a big, important thing.”

Also a founding member of the Red Hook Art Project under the tutor Deirdre Swords, who began creating art alongside Red Hook students on Saturdays in Coffey Park in 2006, Cuevas went directly to Jill Eisenhard at RHI when RHAP needed a new indoor space to hold its art-making sessions. Because RHI was less busy on weekends than on weekdays, Eisenhard was able to make room for RHAP inside the Hicks Street building.

Eventually, Cuevas found another outlet for his creativity in food, and he joined RHI’s Teen Chefs, which “made me understand why I wanted to join the food industry, what I wanted to do in the food industry, and how I wanted my food to affect people.” The program “was a little bit of how to cook, because a lot of us teens didn’t really know how to cook, but it was also about the food industry, so you got to talk to a lot of local chefs, a lot of local business owners. You got to try out a lot of local foods. But the main thing was really understanding that a lot of the people we met were just like us. They were artists, they were – I don’t want to say poor, but they were from low-income communities, and they found their way to make their dreams. Whether it was a small restaurant or a big restaurant, they found a way to make it happen.”

Before long, Cuevas was employed as a prep cook, dishwasher, and busser at Narcissa, the restaurant at the Standard hotel in the East Village. He now works at the Brooklyn Moon Cafe and hopes one day to own his own restaurant. “RHI kept me constantly employed – just going there, using the computer, and then they always had jobs on the board when you first walked in. I would always go up to the board and just check to see what jobs are available,” he remembered.

Cuevas knows plenty of other kids who profited from their years at RHI, including his younger siblings, one of whom took a robotics course there. “All the people that go there, I’m pretty sure they appreciate the quality of people that works there. When you meet one person that really cares for something that you care for, or one person that really wants to help you move forward in life, that’s cool, but when you meet a group of people that’s working in this nonprofit organization that really wants the best for the whole neighborhood, that really wants the best for everybody and wants to help them as much as they can, it’s almost shocking. It’s like this is the first time you’ve seen kindness being put to another human.”

He continued: “I know kids that was selling drugs and doing stuff that they shouldn’t be doing, and going to the RHI has helped a lot of these kids get out of that path, pushed them away from that path. And it’s not like they wanted to be on that path, but the way life gave them these cards they was dealt, they had nothing to do but play them.” As Cuevas put it, RHI managed to “get them a whole new set of cards, a whole new dealer, and get them away from the streets.”

Eisenhard’s personal involvement set an example that still inspires him. “It really grew on me to want to help people – just help them realize how much they’re worth and how much they can really accomplish in their own life and how they can be, truly, honestly, whatever they want to be,” he said. Asked whether he could think of any negative aspects of RHI’s operations, Cuevas paused to think for a moment and then gave a succinct reply: “No.”

If, for whatever reason, one does want to hear something negative about the Red Hook Initiative, the easiest place to go may be the Red Hook Houses West Tenants Association. Bea Byrd, who served as TA president from 1995 to 2000 and remained involved thereafter, provided some historical background to an animus that still exists, in some form, to this day.

As president, Byrd’s “first task was to establish that the tenant association was an inviolable organization in the community that represented the tenants of public housing.” At the time, the larger political structure in Brooklyn had marginalized Red Hook on the whole and the Red Hook Houses in particular. At Community Board 6, until Byrd earned a seat, “Park Slope was recognized, Carroll Gardens was recognized,” but if someone from Red Hook “stood up to say something, you were sort of written off.” NYCHA tenants “had no vote on the community board.”

Later on, Byrd found that, in a way, the Red Hook Initiative had co-opted her mission to give her neighborhood a voice. “They would have things like, ‘Let’s go out into the community and find all the problems that the residents are having that the tenant association is not taking care of,’” she described. “I’ve never had any real connection with Jill. I would see her – she would know who I was; I would know who she was. But there was never any feeling of ‘let’s form a partnership, and let’s work collectively.’ It was: ‘Red Hook Initiative is doing everything in the community, and the tenant association is not.’”

Besides bringing public housing concerns to CB6, Byrd’s priority was “helping people to get jobs. The businesses around the neighborhood didn’t hire locally. All of the people would come to their jobs from out of the community, and I’d argue that we had people here who were qualified – just give us a chance to place them.” RHI has played a similar role more recently, and Byrd acknowledged that the two organizations’ “goals, of course, were pretty much the same, if you’re looking to uplift people in the community and help them have a better quality of life. So I never had any problem with their goals and aspirations.” But RHI was “funded by the mayor’s office. They had their fundraiser where they would raise millions and millions of dollars. The tenant association had nothing like that; we only had volunteer people. Only on one occasion, we got a grant, and I was able to hire someone to be in the office during the daytime hours, because I always had to work for a living.”

Byrd herself, as TA president, acted as a volunteer. “But recognizing leadership, whether you are the leadership of Red Hook Initiative or leadership of the tenant association or the leadership of other organizations in the community – certainly one leader should recognize another, and I just don’t think that was reciprocal.”

Lillie Marshall, the current TA president, who succeeded Byrd, was blunter: “Personally, I call it disrespect, because I was here before [Eisenhard] came here. She never once tried to reach out to me, so I have no reason to reach out to her, because I was already here.” In Marshall’s view, Eisenhard “does not serve anyone in Red Hook. A few kids go there and work for her periodically. I personally feel she’s done nothing. Red Hook was here before she came here, and Red Hook will be here when she’s gone.”

Red Hook stalwart Wally Bazemore attributed the apparent feud to a simple cause: the TA presidents are “jealous. And I spoke to them before – at least Lillie – about, hey, look, you got your own 501(c)(3): you need to put in a program where we could do some holistic stuff for the youth, because it’s not a one-shoe-fit-all.” But Marshall “has to focus on the kids and not how much money is going to RHI. She could get the same grant. There’s plenty of money in this city. There’s a pipeline of money, but you have to find that pipeline and write a proposal. She could do exactly what Jill does. Stop backbiting.”

Bazemore approves of RHI. “I always thank the executive director every time I see her for the things that she’s doing for the kids in the community, giving them a stipend, giving them another outlet, showing them a specific direction. They’re the only ones doing it, so we could all criticize what they’re not doing, and it’s obvious, but if we’re not doing anything, we should just shut up and allow them to do something.”

The most recent public records show $4 million in annual revenue and $2.5 million in assets for the Red Hook Initiative, whereas NYCHA allocated $19,519 for the West Tenants Association in 2018, to add to $61,086 in held-over funds. The question as to whether a facility for fundraising should determine community leadership is a complicated one, but there can be complications, too, in the role of the tenants association within a public housing community. It may appear as a more organic model of self-organization and self-determination than RHI’s system of supervised empowerment, and indeed it may be, but to assume so automatically ignores a history of occasional complicity, in American cities, between tenant leadership and public housing authorities, where the former can sometimes function as a puppet regime, working to quell dissent on behalf of an inadequate state or city agency.

According to Red Hook Houses resident Karen Blondel, Marshall’s monthly TA meetings regularly ignore the established bylaws that are supposed to govern the structure of such meetings, and the resulting chaos makes it difficult for residents to organize effectively around problems in the development or the deficiencies of NYCHA. Blondel claimed that, when she tried to run against Marshall in TA elections, she found herself subject to police intimidation and the threat of eviction.

She believes that NYCHA keeps Marshall in power, despite impeachable derelictions of duty, because “they know how far she’ll go. They’re more comfortable sticking with the status quo.” By contrast, “when organizations like the Red Hook Initiative come out here and embrace our children, it’s a threat to the powers that be. No, it doesn’t work perfectly, but they have programming. What programming does [Marshall] have?” Blondel alleged that the bulk of Marshall’s TA excursions have exclusively served the members of her own church. “She wants to be a dictator over Red Hook forever, and it can’t happen anymore. Conditions have deteriorated. Rents are high. It’s unacceptable.”

In Blondel’s view, one of NYCHA’s worst offenses during her time in public housing has been its refusal to uphold the mandates of Section 3 of the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968, which “requires that recipients of HUD funds, to the greatest extent feasible, provide job training, employment, and contracting opportunities for low- or moderate-income residents in connection with projects and activities in their neighborhoods.” Although the purpose of the law was to force HUD contractors to employ public housing tenants for construction and maintenance projects in the complexes where they live, in New York City it technically allows for the hiring of anyone who makes less than $48,000 a year in the five boroughs. Blondel thinks that NYCHA permitted its contractors to practice employment discrimination in Red Hook (and elsewhere), by which they deliberately ignored local candidates and filled out their positions instead with new high school graduates from less impoverished areas. In part, this neglect on the part of NYCHA created the need for a nonprofit employment and job training center like RHI to enter the neighborhood.

In Blondel’s view, one of NYCHA’s worst offenses during her time in public housing has been its refusal to uphold the mandates of Section 3 of the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968, which “requires that recipients of HUD funds, to the greatest extent feasible, provide job training, employment, and contracting opportunities for low- or moderate-income residents in connection with projects and activities in their neighborhoods.” Although the purpose of the law was to force HUD contractors to employ public housing tenants for construction and maintenance projects in the complexes where they live, in New York City it technically allows for the hiring of anyone who makes less than $48,000 a year in the five boroughs. Blondel thinks that NYCHA permitted its contractors to practice employment discrimination in Red Hook (and elsewhere), by which they deliberately ignored local candidates and filled out their positions instead with new high school graduates from less impoverished areas. In part, this neglect on the part of NYCHA created the need for a nonprofit employment and job training center like RHI to enter the neighborhood.

Nationwide, the rise of the nonprofit sector can be traced alongside the neoliberalization of the United States’ political economy and the erosion of the New Deal. Between 1980 and 2008, the number of registered 501(c) organizations doubled. In 1985, Governor Mario Cuomo echoed the prevailing wisdom of the Reagan era when he declared, “It is not government’s obligation to provide services, but to see that they’re provided.” This included social services. Instead of directly addressing the needs of the public, the government began to channel a portion of the funds that had once powered large-scale social programs, now dismantled, into a competitive marketplace of tiny nonprofits, which jockeyed for grants from other sources to fill out the rest of their budgets. Entrusting the social welfare to a patchwork of small, private entities – each of them relatively powerless in comparison to government itself – helped not only to save money but to ween Americans off the idea that the state had an obligation to provide a minimum standard of living for all its citizens, who thenceforth could expect only charitably disbursed scraps.

In the absence of a guaranteed, taxpayer-supplied budget, these nonprofits had to function, in some ways, as pragmatically as for-profit corporations. Writing in 2017, the activist Andrea Smith describes how, “after being forced to frame everything we do as a ‘success,’ [nonprofits] become stuck in having to repeat the same strategies because we insisted to funders they were successful, even if they were not. Consequently, we become inflexible rather than fluid and ever changing in our strategies, which is what a movement for social transformation really requires.” Stephanie Guilloud and William Cordery of the Atlanta-based nonprofit Project South elaborate (circa 2007): “Our work becomes compartmentalized products, desired or undesired by the foundation market, rated by trends or political relationships rather than depth of work. How often do we hear that ‘youth work is hot right now’?”

By Ortega-Williams’ account, the Red Hook Initiative, which began under the auspices of Long Island College Hospital as a temporary public health program for adult women, came to youth work naturally. “The first program was Community Health Educators, so they were women in the community, leaders in the community, who wanted to learn about reproductive health and share this information with their peers. For the second program, after these women brought in their children or their neighbors, which were young people, we decided to design a Peer Health Educator program for 14- and 15-year-olds. And that was our first adolescent program. After we trained this fantastic cohort of young people, we wanted to continue their growth and development within the organization, so I designed a Peer Counselors program as their second level of training.” From there, “we started to think about where we wanted our focus to be and where we could have the most impact and what our strengths were.”

Incidentally, however, RHI’s youth focus also reflects a preference in philanthropy for an opportunity-based model of social change. Whereas any demand for decent wages for the uneducated and the working class or a guarantee of material comfort even for the unemployed would amount to no less than a call for revolution in the United States of the 21st century, the language of “opportunity” can countenance vast inequality in the class structure, as long as accessible pathways exist for ascent from the bottom to the top. These pathways are designed for the bright, ambitious youngsters of underprivileged communities, not for their parents or grandparents, who have already missed their chance.

RHI board member Brandon Holley extends the ladder of socioeconomic mobility to local kids by hiring them at her startup. “I have employed a number of them, one of whom is [now] with Goldman Sachs, which is kind of cool. She’ll make more money than I ever will,” she remarked. It’s hard to imagine a clearer distillation of the insufficiency of “opportunity” than this invocation of Goldman Sachs, the Wall Street gangsters whose inveterate greed and criminality just a decade ago helped erase $22 trillion of American wealth, with blue-collar families and immigrants footing the bill in one way or another. (Goldman Sachs Gives is an RHI sponsor.) If, in order to get ahead, a kid from a poor, black neighborhood ends up participating in the system of finance capitalism that works to ensure that the majority of black people in America will be poor forever, we might want to envision a society in which getting ahead is no longer quite so essential.

Red Hook Houses resident Henrietta Perkins worries that RHI’s lesson for young people is to “escape from the projects; don’t look back.” In Perkins’s words, RHI is “very informative as far as teaching people things,” but “they’re not checking to see whether whoever they’re giving this information to is improving the neighborhood. They’re improving people, but they’re not improving the community.”

“To garner funding, nonprofits are usually required to develop single-issue campaigns that address some oppressed group, based on age, race, sexuality, disability, or some other identity,” writes College of Staten Island professor John Arena, who postulates in a 2012 book that this fragmented approach is designed not to yield any cohesive mass movement for social justice. For RHI, the focus is young people, but in fact the organization also has an all-ages sideline in emergency preparedness, thanks to the role it played in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy.

When Sandy struck in 2012, the Red Hook Houses lost electricity, heat, and water, but the RHI building remained intact, and the organization quickly opened its doors to provide hot meals, flashlights, and medical assistance, serving as many as 1,200 people a day at 767 Hicks while canvassing NYCHA homes and encouraging volunteers from all over to come to Red Hook to help. In the process, it became the public face of Red Hook’s recovery effort, and the report it issued in 2013 is surprisingly candid about the extent to which the crisis had generated positive publicity for the nonprofit, noting that, soon after the storm, the number of RHI’s Twitter followers jumped from 350 to 3,700 and its Facebook Likes from 150 to 2,760. Its financial documents tell the story even more clearly: in 2011, RHI pulled in $744,144 in revenue, and the next year, that figure rose to $2,471,008. According to Byrd, the “perception was that they were the ones that, when a hurricane comes through – I’ll give credit where credit is due; they were very involved with it, helping people, but so were other organizations,” including neighborhood churches and the Joseph P. Addabbo Family Health Center.

Subsequently, RHI developed a disaster readiness curriculum for Red Hook residents called Local Leaders. Andrea McKnight, who graduated from the program in 2014, values the training she received: she learned CPR; identified potential hazards in her building; took note of elderly and infirm tenants who might need extra assistance in the event of an evacuation; and helped develop an action plan for a future disaster, with five meeting points spread across the neighborhood. “We did a lot of stuff,” she said.

Although the notion of leadership here is not strictly limited to the subject of emergency management, Perkins, also a Local Leader, agreed on the merits of the course but finds it strange that so much of RHI’s limited adult programming remains Sandy-centric six years after the storm. “They keep repeating the same classes we took. . . . How many times can you redo these classes?” she wondered. In a 2015 interview with LinkedIn, Eisenhard admitted to the “potential for mission drift during Sandy,” but RHI managed to stay largely in the business of youth work. Even so, its funding has never come close to dropping to pre-Sandy levels.

The Red Hook Initiative gets 20 percent of its revenue from government sources like the New York City Department of Youth and Community Development and the New York City Human Resources Administration, 13 percent from individuals, 12 percent from corporations, one percent from earned income, and 55 percent from private foundations.

The Red Hook Initiative gets 20 percent of its revenue from government sources like the New York City Department of Youth and Community Development and the New York City Human Resources Administration, 13 percent from individuals, 12 percent from corporations, one percent from earned income, and 55 percent from private foundations.

Faced with the prospect of losing 40 percent of their wealth (or, in the old days under FDR, as much as 77 percent) to the estate tax, aging plutocrats commonly elect instead to funnel huge chunks of their fortunes into tax-exempt private foundations, which, through donations, convey these monies back into services primarily for plutocrats: elite universities; opera houses; and, most crucially, right-wing think tanks that promote anti-welfare policies, supply-side economics, and imperial wars. In order to legitimize these tax havens in the eyes of the public, foundation-based philanthropists sometimes make donations to organizations that meet a more traditional standard of what constitutes a charity, like the Red Hook Initiative.

RHI’s most generous donor, for example, is the Carson Family Charitable Trust, which also gives to Dartmouth College; the Columbia School of Business; charter schools; the free-market Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, which has pushed for Medicaid cuts, advocated against raising the national minimum wage, and championed fracking; and the neoconservative American Enterprise Institute, whose senior fellows have included Trump’s national security advisor John Bolton and former vice president Dick Cheney. In 2016-2017, the Trust gave $1 million to RHI.

The IRS requires private foundations to dispense only five percent of their assets in a given year (administrative costs can account for part of this figure), and while most prefer to grow their endowments than to spend them in full, the wealth of private foundations – half of which have appeared within the last 20 years – nevertheless confers upon them an outsize role in determining America’s prescriptions and solutions for the problems of poverty and social injustice. In his 2018 book Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World, Anand Giridharadas posits that “when elites assume leadership of social change, they are able to reshape what social change is – above all, to present it as something that should never threaten winners. In an age defined by a chasm between those who have power and those who don’t, elites have spread the idea that people must be helped, but only in market-friendly ways that do not upset fundamental power equations.” Giridharadas promotes a more democratic method, noting that “if you are trying to shape the world for the better, you are engaging in a political act, which raises the question of whether you are employing an appropriately political process to guide the shaping.”

Organizations like RHI operate, in part, as functionaries of the foundation world, whose funding allows them to offer much-needed social services while simultaneously problematizing their relationship to social change. Yet RHI’s mission statement emphasizes “social change to overcome systemic inequities,” and its slogan is “We Are the Change.” While 501(c)(3)s are legally prohibited from advocacy on behalf of candidates for public elective office, RHI has conducted studies and surveys that have helped lead the push to remove dangerous lead and mold from NYCHA apartments. There’s evidence that the RHI environment is conducive to civic-mindedness for its young people, who take part enthusiastically in District 38’s Participatory Budgeting and, some years ago, even initiated a study of their own to demonstrate the large discrepancy in the number of public trash cans between the Front and Back of Red Hook, which, in addition to explaining a litter problem in the underserved Front, pointed usefully to a larger theme of the city’s neglect.

Earlier this year, RHI assembled an Anti-Violence Research Group of eight young people to “investigate the roots of peers’ violent experiences and ways to reduce violence within the neighborhood.” The researchers identified “aggressive policing” as “a major contributor to experiences of violence for young people.” When the Star-Revue glimpsed an early presentation by the Anti-Violence Research Group and published a pro-police response, RHI regarded this press intrusion as an invasion of privacy and an endangerment of its young people and determined to shelve the report indefinitely.

In America’s culture of authoritarianism, anti-police sentiments, no matter how valid, will always attract controversy, and RHI’s reluctance to garner media attention (whether hostile or sympathetic) for its own project prompts the question whether the study was meant to be only an internal exercise in simulated activism, defanged by the private, academicized context into which the findings would be channeled. Left without guidance, adolescents in the Red Hook Houses, whose childhoods witnessed the trauma of the NYPD’s brutal 2006 drug raid, might come to theorize, for example, that – because the presence of the police in black neighborhoods fundamentally amounts to a military occupation, transforming daily community interactions into potentially deadly scenarios in any number of ways; or because the police, as defenders of private property, serve only to contrive social order (violently if necessary) within a system in which poor people are exploited – perhaps the NYPD shouldn’t exist at all. But it’s difficult to picture the Rockefeller Foundation donating to an organization seen promoting such ideas or the direct action that such ideas would compel.

RHI’s official 2018 Impact Report sums up the anti-violence research: “The team developed a report including findings and recommendations, and utilized the findings to fuel advocacy. Over the next year, RHI will support the team’s recommendations to reduce violence by increasing opportunities for youth to imagine, design and lead community activities, events and programs.” In other words, the solution to neighborhood violence is more RHI. The police go unmentioned.

Per Arena, nonprofits can provide a “protective function” for capitalism, “centered on their capacity to undermine, contain, or prevent the emergence of social movements that challenge the power and prerogatives of the ruling class. One key way nonprofits contain movements is through co-optation of leaders or, as Hester Eisenstein puts it, ‘by sopping up the energy of activists.’ . . . Central to the recruiting and co-optive powers of nonprofits and their foundation sponsors is the material rewards they can provide intellectuals – the ‘jobs and benefits for radicals willing to become pragmatic.’ These perks, along with the legitimation that comes with being associated with ‘progressive,’ ‘humanitarian,’ and/or ‘social change’ organizations, can be useful in both peeling away working-class, grassroots, organic intellectuals or preventing others from even dabbling in radical politics.”

Per Arena, nonprofits can provide a “protective function” for capitalism, “centered on their capacity to undermine, contain, or prevent the emergence of social movements that challenge the power and prerogatives of the ruling class. One key way nonprofits contain movements is through co-optation of leaders or, as Hester Eisenstein puts it, ‘by sopping up the energy of activists.’ . . . Central to the recruiting and co-optive powers of nonprofits and their foundation sponsors is the material rewards they can provide intellectuals – the ‘jobs and benefits for radicals willing to become pragmatic.’ These perks, along with the legitimation that comes with being associated with ‘progressive,’ ‘humanitarian,’ and/or ‘social change’ organizations, can be useful in both peeling away working-class, grassroots, organic intellectuals or preventing others from even dabbling in radical politics.”

Arena is loosely describing a concept known as the “nonprofit industrial complex” (NPIC), and UC Riverside professor Dylan Rodríguez, in a 2007 essay, extends the point: “The NPIC is not wholly unlike the institutional apparatus of neocolonialism, in which former and potential anticolonial revolutionaries are ‘professionalized’ and granted opportunities within a labyrinthine state-proctored bureaucracy that ultimately reproduces the essential coherence of the neocolonial relation of power itself.”

For those who believe that, in the modern era, foreign-aid NGOs have replaced colonial governments as a means for the Global North to exercise dominion over the Global South, it may be worth asking whether certain demands for structural decolonization are warranted in the domestic nonprofit sphere. While some may argue, possibly correctly, that Red Hook residents power the internal engine of RHI, with board members primarily in charge of fundraising to support their activities, Holley claimed that RHI board members are “very active. I think we have a really good, almost model board. In fact, a lot of people say that our board is a model for their organizations because we’re actively involved in every aspect of [RHI].”

Byrd believes she could have been a candidate for a board seat if RHI had had more trust in the community it served. “I’ve been a president of the NAACP for the entire borough of Brooklyn. I’ve been on the Community Board. I’ve been on the Housing Authority board. I just recently left the Joseph P. Addabbo board. I know that boards and board members are very important. It’s OK to say, ‘I hired a young person from the community to be an outreach person.’ But who’s sitting on the board of directors of Red Hook Initiative? They could all be wonderful people, but how many of them actually live in the Red Hook Houses where you’re located? When you talk about the body that makes the decisions, who do you have from the Red Hook Houses that’s making those decisions? Probably no one.”

The 2007 anthology The Revolution Will Not Be Funded (South End Press) notes the “immense social division” between “foundations and marginalized social groups,” especially groups of color, whereas, for “the white Left capitalist, foundations are often only a phone call away.” This volume, compiled by the nonprofit INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence after the Ford Foundation withdrew a $100,000 grant in reaction to the group’s support for Palestinian liberation, begins with a simple self-directed question: “Do you think the system is really going to fund you to dismantle it?”

While foundation dollars dwarf corporate donations at the Red Hook Initiative, the corporations that contribute to RHI tend to have a greater involvement in the Red Hook community, which invites increased scrutiny. For companies whose philanthropy functions as a public-relations tactic, charitable donations don’t necessarily entail the same expectation of quid pro quo as political contributions: the donation is an advertisement, true or false, of the company’s good will for the community and doesn’t inevitably carry a set of instructions for its recipient. But it does reveal a relationship of some kind between the company and the charity. For example, if the goal of the company were to gentrify Red Hook, it would be unlikely to make its donation to an explicitly anti-gentrification organization – which one might logically assume any organization serving low-income people would be.

Especially prominent among RHI’s sponsors are real estate developers, including Forest City Ratner, Two Trees, the Sitex Group, and the O’Connell Organization. The plans of the real estate interests to change the character of Red Hook in ways unlikely to benefit low-income residents are clear. “Possible upzoning of Red Hook could allow for more FAR [floor area ratio] and might make this ideal for a boutique condo development,” hints a recent Red Hook property listing at Corcoran Real Estate, another RHI sponsor. Local activist Robert Berrios sees it this way: “Their whole idea is to convert Red Hook into another Williamsburg or Chelsea or one of these yuppie neighborhoods.”

In some cases, real estate donations appear nakedly transactional. In 2016, while pursuing plans to build a 1.2-million-square-foot waterfront office complex called the Red Hook Innovation Studios, the Italian company Est4te Four donated to RHI; in 2017, after giving up on the idea and unloading all but one of its Red Hook properties onto the Sitex Group, Est4te Four disappeared from the list of sponsors, replaced by Sitex, whose vice president Zach McHugh now sits on the RHI Associate Board. Meanwhile, in 2016, the engineering juggernaut AECOM released an unabashedly grotesque plan to transform the Red Hook Container Terminal into a shiny, towering wall of 45,000 subway-serviced luxury condominiums. A Thrillist article quoted a subsequent remonstrance by Eisenhard, whose objection related to AECOM’s lack of community outreach, not to the substance of the proposal: “The [correct] process would be engaging residents to ask, ‘What are the needs you see?’ . . . And take that and then develop a plan.” In 2017, AECOM became an RHI sponsor.

Why do real estate developers like RHI? While any suggestion that a well-loved community-based organization could be in a good position to smooth out legitimate local opposition to the sort of massive, disruptive development favored by Forest City Ratner, the company behind Downtown Brooklyn’s unpopular Pacific Park (formerly Atlantic Yards), might carry some tone of a conspiracy theory, Byrd mentioned that she’s been fascinated by New York real estate developers since the emergence of Donald Trump in the 1970s, and in her view, such businessmen “are not doing something for nothing. They’re not giving you money out of the kindness of their heart. They’re giving you money because they expect something in exchange.” Whether or not RHI can sway local opinion, the imprimatur of a nonprofit intimately ensconced in the neighborhood might, for city officials weighing land-use approvals, plausibly stand in for the notion of community support.

So far, Eisenhard’s personal advocacy for the Brooklyn-Queens Connector – a project conceived to boost waterfront property values, pushed by the real estate lobby and adopted by Mayor de Blasio – has yet to convince Red Hook that it’s a good idea. While light rail may not outperform bus service in terms of speed, convenience, or reliability, it does have the advantage of being far more expensive, which allows it to function as a symbol of the overall civic investment bestowed upon wealthy neighborhoods. Rich people don’t ride buses. They may not ride the BQX that much either, but its presence will hearten them because, from it, they’ll know that the city has wrested Red Hook from its former squalor and poured in a bunch of money in anticipation of their own arrival. In short, it tells them that Red Hook belongs to them now.

Supposedly, the city expects a financing model known as “value capture” – which refers to the increased property tax revenue that comes from growth in property values in the wake of improved public services, without an increase on the tax rate – to fund the BQX, but last year a leaked memo from City Hall acknowledged that this mechanism was unlikely to cover the cost. The most recent BQX map has abandoned the plan to run the streetcar down crowded Van Brunt Street, shunting it instead onto Columbia Street and Bay Street, which, since the Red Hook Houses and the Red Hook Recreation Center sit on publicly owned land, would largely invalidate the premise of “value capture,” at least in Red Hook, unless some of that land were privatized.

Berrios said that he knows the BQX isn’t meant for anyone in the Red Hook Houses because de Blasio has yet to secure a guarantee from the MTA for a free transfer between systems, despite promises to do so; by and large, Red Hook natives can’t afford to pay twice for their commute to work. “This is the thing: if [RHI is] supporting this, all these students that they’ve been teaching and helping, they’re all going to be gone because they’ll have to move out of the neighborhood,” Berrios explained. “So they’re saying they’re here to help the community, but they’re supporting this. It doesn’t mix well.”

Berrios’s apparent implication – that the BQX, if it were built, would spell the beginning of the end for public housing in Red Hook – may sound hyperbolic. NYCHA, which owns 328 campuses, has knocked down only one in its 84-year history.

But public housing residents in many other cities have been less fortunate, and for some observers, NYCHA’s recent dysfunction has suddenly made eerily plausible the notion of giving up, on a collective level, on its 178,895 homes. In March, the New York Daily News opined that “New York City is at a crossroads. If its public housing is allowed to deteriorate further, the buildings will soon seem too dilapidated to save. They will become more dangerous, the cost of repairs ever-more insurmountable. Some terrible harm to residents will come to define NYCHA’s cruelty, and the value of the real estate on which the buildings sit will emerge as an irresistible lure. By then, demolition will be hailed as the only solution.”

Arena, in his book Driven from New Orleans: How Nonprofits Betray Public Housing and Promote Privatization, writes, “Central to the gentrification of U.S. cities has been the destruction of public housing,” which is generally seen as “a blight on the neighborhood,” its dilapidated buildings as “physical and social obstacles to economic regeneration.” Published by the University of Minnesota Press, the volume tells the story of the nonprofit organizations that, purporting to represent low-income city-dwellers but compromised by their ties to government and real estate interests, paved the way for the full-scale destruction of the Housing Authority of New Orleans, which at its peak housed 60,000 people and now owns only a few scattered buildings. The rest were demolished in favor of lower-density, mixed-income, privately managed developments – first, slowly, by way of HOPE VI’s promise of superior housing; then, once Hurricane Katrina had given the city an excuse to evacuate the projects (some of which bore only minor damage), more rapidly, in a manner that many regarded as an ethnic cleansing. For public housing residents living on a floodplain during global warming, the history of New Orleans – in which tenants associations and mainstream activist groups gave in to demolition and privatization, believing there was no alternative – puts forth a chilling warning.

The author points out that, after Katrina, nonprofit relief efforts, like Habitat for Humanity and the Make It Right Foundation, helped “foster the illusion that philanthropic efforts could rebuild the city,” ultimately diverting “hundreds of thousands of volunteers into repairing and constructing homes and providing other services rather than incorporating them into a movement to defend public housing and advocate for a public works program to rebuild New Orleans and the gulf.” It can seem cruel to blame private altruism for providing “political cover for the government’s abandonment,” but the idea deserves engagement.

By RHI’s estimation, 50 to 60 percent of families in the Red Hook Houses don’t have internet access in their homes. While the FCC allows for broadband to be priced as a luxury, it’s in fact an essential utility, and those without it face enormous, unfair obstacles not only in finding and holding jobs but in participating in society on a basic level. Outside the logic of neoliberalism, the obvious solution to the “digital divide” in Red Hook would be to demand that NYCHA provide free broadband in every housing unit. Inside neoliberalism, the answer is for the Red Hook Initiative to hire kids (called Digital Stewards) to install a resilient mesh network of antennae on neighborhood rooftops, thus demonstrating the power of local resourcefulness and innovation while also teaching valuable tech skills to young people who, technically, still don’t have internet at home. One can connect to RHI’s Red Hook WIFI in the streets, but it doesn’t penetrate the Red Hook Houses. Even so, it generates reams of feel-good media coverage, and in this way, the problem is psychologically resolved, even if the digital divide remains – society is taking care of the issue (sort of), without any need for us to stand up to governmental austerity.

In October, RHI acquired fellow nonprofit Added Value Farms. Added Value had operated the Red Hook Community Farm on Columbia Street, which grows more than 20,000 pounds of produce annually; and, in partnership with the AmeriCorps program Green City Force, the NYCHA Farm on Wolcott Street, which “engage[s] residents in urban food production and healthy eating.” Urban farming has recently emerged as a trendy solution to the problems of food deserts and unwholesome diets in underserved communities, where, thanks to the efforts of plucky locals (and, now, RHI kids), organic kale and zucchini spring up on formerly abandoned lots. In fact, the United States already produces more food than any nation except China and India – so much, indeed, that 30 to 40 percent of our food ends up in the trash. If any household in America experiences food insecurity, or if anyone is cut off geographically or economically from fresh, healthy produce, it speaks only to a monstrous system of resource distribution, not to a need for individuals to pick up the slack by growing more food.

Whatever environmental or ethical problems may exist within our industrial food system, the limited proliferation of urban farming – conceived more often as a sort of horticultural therapy with edible rewards for a pathologized underclass than as a popular movement for all – doesn’t effectively challenge it. It offers some jobs and a certain skill set, but by more subtly proposing that in the end it may be an act of greater kindness to transition the undernourished bodies of America’s sacrifice zones back to subsistence farming than to let them keep waiting in vain for legitimate local investment within the free market, it abets their marginalization, hinting that – in a country whose citizenry has otherwise largely been liberated from agriculture – they may ultimately have to fend for themselves nutritionally, with the help of a few green-thumbed do-gooders, rather than ever receiving an equal share in the bounty of the nation.

Writing in 1848, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels assert that a “part of the bourgeoisie is desirous of redressing social grievances, in order to secure the continued existence of bourgeois society. To this section belong economists, philanthropists, humanitarians, improvers of the condition of the working class, organizers of charity, members of societies for the prevention of cruelty to animals, temperance fanatics, hole-and-corner reformers of every imaginable kind.”

For her part, Ortega-Williams acknowledged the smallness of an institution like RHI in the face of large-scale injustice. “Even though it’s an organization that would be considered mid-size, it’s small in the face of the historical patterns of violence that people have experienced, the historical patterns of racism,” she said. “You want all the best for people and know that, literally, there are enough resources for everyone to have what they need.” To her, the role of the nonprofit is, in part, “to stand in the gap along with young people and their families who are saying they deserve more. . . . I think RHI does a really great job of seeing people heartened and hopeful and imagining. Having a fueled imagination is important.” (“The logics of the NPIC may structure the work that takes place in any given organization, but it does not fully account for or subsume it,” write Soniya Munshi and Craig Willse in the INCITE! anthology.)

The Red Hook Initiative didn’t invent neoliberalism; it simply does what it can with the model for social aid that’s possible under its dictates of austerity and privatization, and the results, all considered, appear strong. But at a time when it seems increasingly plausible that everything except radical anti-capitalism essentially amounts to climate denial, some kids in Red Hook may, finally, look elsewhere for social change. Soon enough, even Valentino Pier will be privatized, at least in a certain sense – that is, it’ll be claimed by the rising sea levels created by the rapacity of private industry. When that happens, RHI will still be working nobly to raise the high school graduation rate in public housing. The Carson Family Charitable Trust will still be pouring its benevolence into the world it simultaneously seeks to ruin for all but the elite. And in Red Hook, the young people will have to decide for themselves what must be done.