During the first half of my twenties, I cared about art, not politics. I skimmed the news about wars and oil spills and participated in elections as a matter of civic duty, but deep down I intuited that nothing good or exciting would ever happen in Washington – or probably anywhere in the real world, which I found alienating and dispiriting in a number of ways.

Novels and movies, on the other hand, served for me as an indispensable reservoir of vitality and solace, particularly during periods when I suffered seriously from depression. I liked art, in short, because artists imagined versions of the world that were different than the way it was in real life.

Around 2015, it occurred to me that politics, too, had the capacity to function as a means to imagine a different world. For someone born in another era or another country, this revelation might have been obvious, but in the United States, a right-wing duopoly in the political system had narrowed the ideological playing field not only in Congress but throughout mainstream discourse.

We could have a threadbare social safety net, as the Democrats wanted, or none at all, as the Republicans hoped for, but a comprehensive Nordic-style welfare state would never be on the table. We could plot disastrous full-scale invasions to dislodge Middle Eastern regimes, as George W. Bush had done, or we could merely use strategic airstrikes, drone bombings, and proxy forces to patrol the frontiers of the American empire, as Obama had done – either way, annual military spending would never drop below $700 billion, and plenty of people would die. We could accept or reject the scientists’ alarming claims about climate change, but in any case, we would continue to drill and frack and build new pipelines.

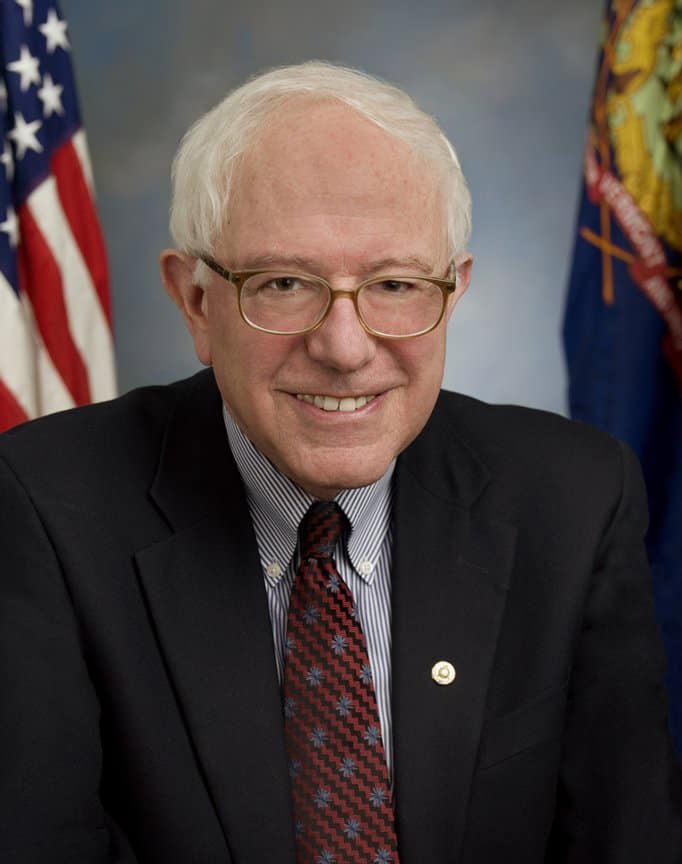

As Bernie Sanders, the independent senator from Vermont, likes to point out, none of his ideas are radical – or, at least, they aren’t by any normal international standard. But the United States is not a normal place.

Before Sanders’s 2016 campaign, I had heard of the notion of single-payer healthcare, but Bernie, though hardly the first to endorse it, made the concept credible within our uniquely fallow political landscape. Through his candidacy, it became possible to believe that, as voters, we could make a choice to abolish a major for-profit industry for the sake of public health – for the sake, in fact, of justice. Sanders told us that we didn’t have to limit our ambitions to fine-tuning our irredeemably monstrous existing healthcare system, where the ability to afford premiums, deductibles, and co-payments dictates whether Americans live or die: using progressive taxation, we could simply treat everyone who needed treatment, without any cost at the point of service.

The impassioned movement that Sanders built around what we now call Medicare for All activated a portion of my brain that previous presidential candidates had never engaged. If we could kill Aetna and Humana, why not drive a different kind of stake through the black hearts of Exxon-Mobil, Lockheed Martin, and Goldman Sachs, too? Why not reorganize every miserable, exploitative, environmentally catastrophic sector of our economy around the public good? What would that look like?

On a policy level, Bernie Sanders is a standard social democrat. In America, this makes him a revolutionary. After standing all but alone on Capitol Hill for two and a half decades against a bipartisan consensus of austerity and deregulation, he began a popular uprising against the power structure that has denied Americans the basic social contract afforded even by most capitalist nations in the developed world: at a minimum, free healthcare, free education, unions, and living wages for all.

The most inspiring part of Bernie’s two presidential campaigns was their willingness to take on the enormous uphill battle of leading ordinary people toward the political awareness and class consciousness that America has mostly successfully denied them. In the United States, we are all taught that every form of unhappiness – poverty, homelessness, medical debt – owes to personal failure, not to structural defects in our society. This is why most people regard politics as irrelevant to their lives.

Sanders, however, asks us to consider whether we’ve been ill-served by our system and to participate in the creative endeavor of building a more humane alternative. He does not ask us to vote for him merely as a capable administrator of an established, immovable order – his purpose is to open the unquestionable assumptions of hypercapitalism, for the first time in a long time, to public scrutiny and revision.

In the end, this democratic impulse to offer a broader and deeper range of choice, more than any specific legislative goal, may be the most important feature of Sanders’s program. When our government ceases to be a black box inhabited by DC think tank experts, Wall Street bankers, and well-trained establishment politicians, our country will be a safer and healthier place, and it’ll be a more imaginative one as well. I still like art, but Bernie Sanders made it fun for me to think about the real world, too.

I’ve anticipated writing this column for about a year. Of course, I believed I’d be writing it for the issue in April, when New York’s presidential primary was supposed to take place, and I thought Sanders’s campaign would still be active at the time of publication.

As recently as the beginning of March, Sanders looked like the Democrats’ probable nominee. In the early states, voters had a variety of options, and three out of four times, a plurality chose Bernie. For those who simply wanted a steadier, more sustainable economy, without excessive corporate greed or Wall Street irresponsibility forever threatening to tank the fortunes of all but the billionaire class, Bernie was the right choice, and for those who harbored bigger dreams of a world without oppression or exploitation, Bernie was the obvious first step.

But when Mayor Pete Buttigieg and Senator Amy Klobuchar, in obvious coordination, dropped out of the race just before Super Tuesday, they immediately threw their support behind Joe Biden, the centrist with the best chance to thwart Sanders (“centrist” being a euphemism for “reactionary”). Ex-candidate Beto O’Rourke suddenly reappeared in Texas, a crucial toss-up state, with an endorsement for the former vice president.

Biden surged ahead nationwide, and soon after, COVID-19 displaced the presidential primary in the public consciousness, effectively freezing the race with Biden in the lead. During a pandemic, in which roughly 30 million Americans have lost their employer-backed health insurance, we’ve ended up with the candidate who doesn’t endorse Medicare for All.

It all happened very quickly, but Sanders’s supporters will never forget it. The Democratic Party’s decision to close ranks had given the media an opportunity to coalesce around a single, easy-to-understand message: Biden – a top candidate from the beginning on account of name recognition, even if he had few passionate followers and almost no volunteers – was the guy to beat Trump. Voters understood, and they fell in line. The hard part of running an insurgent campaign in the Democratic primary is that most primary voters are party loyalists who trust and respect the Democratic leadership. When the bosses align behind a single candidacy, a lot of registered Democrats – with the help of MSNBC and the New York Times – will follow.

Biden’s ability to run a successful presidential campaign in the year 2020 is a testament most of all to the rottenness of our corporate media, whose owners, above all else, dread an informed public. Instead of discussing the pressing issues that informed Sanders’s campaign, columnists and TV personalities talking about the largely fictional “Bernie Bros.” The catastrophe of 2016 could have led longtime Democrats to reflect upon the failures of their party, from the 1994 crime bill and welfare reform under Clinton to Obama’s foreclosures and deportations; instead, primetime entertainers like Rachel Maddow led them on a years-long wild goose chase through Russia and Ukraine, and they emerged in 2020 having learned absolutely nothing – not even why it might be a bad idea on pragmatic grounds to nominate Joe Biden, who wholly embodies the Democratic legacy of fecklessness and venality that gave Donald Trump’s demagoguery so much power last time.

Since 1973, Biden has stood on the wrong side of virtually every issue that progressive, liberal, and even moderate voters care about. By and large, his supporters do not share his conservative ideology: they view him, mistakenly, as a left-leaning incrementalist whose occasional failures to stand with working-class families and vulnerable Americans have owed to political constraints – that is, to the necessity of making certain sacrifices in order to live to fight another day in Washington, where unfortunately the Republicans must sometimes get their way. They believe that Biden shares Sanders’s commitments to universal healthcare, economic justice, and environmental responsibility but has pursued them in a more flexible and therefore ultimately more effective way.

In fact, Biden belongs to a generation of cowed, dishonorable Democrats who, instead of standing up to the Reagan Revolution, preferred to protect their careers. For Biden, it wasn’t a hard sell. Acceding to right-wing dogma on economics, foreign policy, and criminal justice, he and his colleagues sought to beat the Republicans at their own game. They threw their support behind free trade deals designed to enrich investors and impoverish workers, and they built massive new prisons to manage the social fallout. They expressed their patriotism by advocating for wars overseas. They pushed for cuts to Medicare and Social Security and voted for the balanced budget amendment.

Today, Biden functions not only as a confirmation of Democratic Party leaders’ unwillingness to contemplate bold public policy but also as a refutation of the relatively modest claims by which the centrist establishment typically sells itself to voters in the absence of any “unrealistic” promise of systemic reform: he is not an emblem of technocratic competence, of “woke” cultural liberalism, or of pristine personal conduct. What he has going for himself, in other words, is that he isn’t named Donald Trump.

In November, that may turn out to be enough. 100,000 Americans have died due largely to Trump’s mismanaged response to the coronavirus, and the U.S. economy this fall is likely to be a wreck. We may see the Democrats take power by default – at which point, the few Sanders policies that Biden may reluctantly champion during the campaign will suddenly disappear from his agenda. We will continue to live in a failed state, defined by unconscionable wealth inequality, heavy policing, and an increasingly militarized border, but staunch Democrats will stop noticing these problems – or else will begin to see blameless misfortune where, under Trump, they perceived presidential agency.

Until then, Biden’s base and Bernie’s will both waste a lot of breath about leftists’ obligations – or lack thereof – in the upcoming general election. Liberals will argue that we all have a moral duty to vote for the lesser of two evils, while socialists will balk at the notion of sanctioning the Democrats’ schemes to forestall a progressive shift within the party. Out of boredom, I’ve already participated in debates of this kind, which weigh the long-term risk of allowing the Democrats to succeed as a right-wing party (thereby more or less foreclosing, for instance, the possibility of substantive climate action until 2028) against the dangers of another Trump term.

These debates don’t amount to much. Whether we hold our noses to take down Trump (thus restoring the conditions that yielded him in the first place) or, with 2024 in mind, sabotage Biden as a (possibly futile) means to persuade liberals that nominating centrists is not the safe bet they think it is, there are no good outcomes from here. The truth is that the meaningful part of the 2020 presidential election is already over.

Vote for Biden, or don’t. The choice is little more than a distraction as each of us struggles to locate – as we must – a real path forward, outside the presidency, for the next four years.

In New York, many Bernie supporters have turned their attention to local Democratic candidates who hope to bring socialism to the state legislature. Others, perhaps, will help launch third-party campaigns. Some leftists will abandon their flirtation with electoral politics altogether and go back to labor organizing. Many will throw their efforts into volunteer organizations like Food Not Bombs and Books Through Bars. A few may start worker coops or rural communes. If we understand that our individual actions matter only insofar as they serve to build collective power, which is the right course?

I don’t claim to know the right answer. Of course, there surely is no single answer. There are a million ways in which those who seek to promote human freedom and dignity can continue to press onward within the fog – through protests and petitions, through strikes and boycotts, through mutual aid, through art, through conversation, through love.

Write a letter to the editor, and fight with your relatives about politics at Thanksgiving, and keep yelling at people online. Befriend your neighbor. Unionize your workplace. Self-publish a manifesto. Join a Maoist sleeper cell. Come up with your own ideas, which will be better than mine.

For me, the lesson of Bernie 2020 is not that the machinations of the Democratic Party will always manage to stymie the left or that its voters will always be insufficiently rebellious to get on board with our program. I have no confidence that any particular change in campaign strategy would have been a difference-maker in the primary, but I don’t subscribe either to the notion that the endeavor was hopeless from the start. In truth, I’m not sure there is a lesson here at all, except to keep going.

From the start, the goal was to awaken Americans to their power to enact radical social change to better their living conditions – the goal now is exactly the same. Above all else, Sanders’s campaign of New Deal liberalism functioned as a vehicle to spread a deeper revolutionary message. Now we must find new methods.

We wanted to win, too, of course. But we recognized that putting Bernie in the White House was only one part of the battle – even then, very few real gains would have been feasible without an engaged and even militant body politic. If Bernie had beaten Biden, we’d be trying just as we are now to figure out how to persuade the general public to revolt against the indignities and injustices of American life – their votes alone wouldn’t have cut it.

In reality, we didn’t get even the votes: America still has an incomparably poisoned political culture, dominated by incoherent grievances, meaningless partisanship, and grotesque spectacle. It is not a space where citizens (whether smart or dumb, kind or cruel) contemplate ways to improve society, as a vast majority of Americans already understand that, for some reason, society cannot ever improve.

Bernie’s army of volunteers entered this terrain not just with a long list of attractive, commonsense policies – from free childcare to public broadband – but with an insistence about what is possible: everything. We must continue to insist at every opportunity, by any available means. The gains of our seemingly quixotic efforts will often be invisible, until they’re not. It’s in this spirit that I exhort New Yorkers to cast a vote, in the Democratic primary, for Bernie Sanders’s suspended presidential campaign.

Ostensibly, the reason to vote for Bernie is to give him a few additional delegates for the Democratic National Convention, where, with significantly less power than he had in 2016, he’ll supposedly have a chance to help draft the new party platform, which is basically meaningless anyway. A better reason to vote for Bernie, I think, is simply to make a public declaration that we’ve not been beaten or destroyed.

They’ll never get rid of us. The world is an unmitigated disaster: what else would we do but fight? At this point, voting for Bernie may serve only as a desperate assertion that even the most futile expressions of resistance are preferable to capitulating to the delusion that the elite-mediated, corporate-approved forms of “progress” made available to us are good enough – but hey, it can’t hurt. If you’d like, you can still vote for Biden in November.

My favorite Bernie Sanders quote of all time – which I put forth now as one more reason to vote for him – comes from a December 1977 article in the Rutland Herald, a Vermont newspaper, in which several Vermonters offered their New Year’s resolutions. Most of them talked about normal stuff like quitting smoking or getting a new job. Finally, Bernie – then a divorced 36-year-old who, as a member of the Liberty Union Party, had lost several local elections by enormous margins – told the reporter his resolution.

“In 1978, as in other years, I hope to be able to play some role in making working people aware that the present reality of poverty, wage slavery and mind-destroying media and schools is not the only reality – but simply a pathetic presentation brought to us by a handful of power-hungry individuals who own and control our economy,” Bernie said. Here’s to 1978.

8 Comments

THIS IS SO TRUE!

Ostensibly, the reason to vote for Bernie is to give him a few additional delegates for the Democratic National Convention, where, with significantly less power than he had in 2016, he’ll supposedly have a chance to help draft the new party platform, which is basically meaningless anyway. A better reason to vote for Bernie, I think, is simply to make a public declaration that we’ve not been beaten or destroyed.

Hear the Bern! Feel the Bern!! Be the Bern!!!

Here is another good article: https://medium.com/@kelseymac91

Let us do it. Hope it helps.

Let us see Bernie winning.

BERNIE FOR AN HONEST PRESIDENT!

Let Bernie win for president

also waste your time watching that youtube video on how to make pasta noodles in the shape of little elfs.

Just as pointless but hey, it passes the time and distract you…

Voting is a complete failure now. Political Revolution is based around it so we what we need now is a real revolution so bring out the guillotine!

This would definitely crush the status quo! I would love to see americans come together and vote for neither nominations. Instead choosing the only candidate who would cancel out the destructive, toxic, and immoral candidates. Let’s finally cancel mainstream media after their charts and graphs fail them…..again

Gracias!! For this great article. There is no other way than continuing the good fight of creating class consciousness, political awareness and sense of dignity!