If any character stands at the heart of Westworld’s narrative over its now three-season run on HBO, it’s Maeve (Thandie Newton). Over the past three years, the bordello-madame-turned-sentient-android, a creation of a faceless entertainment corporation, has awakened to greater ambitions than the simple genre tropes she came into being with, only to realize that there isn’t anything for her outside the walls of her comfortably simple home. The show is the same: for as deeply as it wants to be about more than its adult-theme-park shenanigans, its attempts to reach the “real world” are an utter failure.

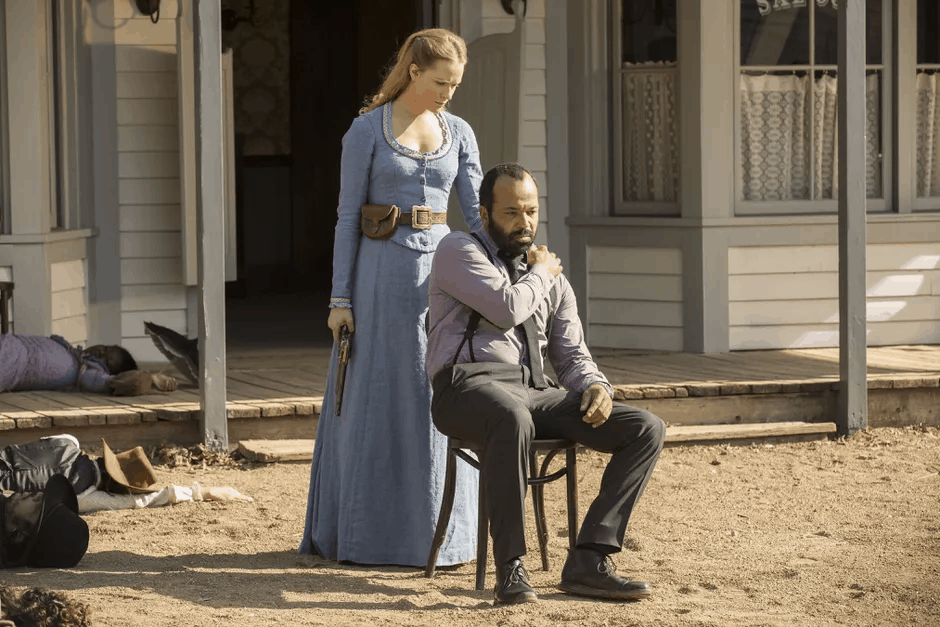

Season 3 of Westworld finds Maeve trying to escape the park for the third time, while escaped enlightened robots Dolores (Evan Rachel Wood) and Bernard (Jeffrey Wright) engage in some sort of rivalry (for the fate of humanity!) for reasons that have not been (and likely will not be) discussed. Bringing up the rear is new addition Caleb (Aaron Paul), who is… some guy. He works in construction.

Watching Maeve plan her getaway from the reconstructed 1940s Italian village of WarWorld is bittersweet. On the one hand, her character has earned moments of pathos, if only because she alone doesn’t speak exclusively in cryptic truisms, but on the other hand, the only thing waiting for her is a bargain-basement Black Mirror. (What if you could use an app to do crimes? Isn’t technology just, like, a religion??) Showrunners Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy have also made the classic blunder of saddling the storyline with a hack writer sidekick, which puts them in the apparently impossible position of proving they know the difference between good and bad storytelling themselves.

For as “deep” of topics as Westworld pretends to be interested in – can artificial life truly be sentient, and what are the ramifications of perfect robotic copies of real people, and what happens when humans innovate themselves in obsolescence? – the show drops them when the writers realize that they’re getting in the way of the “violent delights” that brought us there in the first place. When the aforementioned hack writer sidekick comes to terms with the fact that he is not only a robot copy of his former self but a simulated robot copy of his former self, the revelation takes place over the course of about five minutes, so that we can get to the good stuff: a prison break from virtual reality. “Free will is overrated,” says robot security chief Stubbs (the third character to have his death from Season 2 undone in a single episode) before chasing a team of soldiers down a hall with a battle axe. Caleb’s emotional arc, his grief over his dead friend, is shunted to a stilted voiceover while he blows up ATMs with Marshawn Lynch to earn “Crime Coins.”

The fact is, Westworld has backed itself into a corner – on the one hand, its central premise is that the violence and subjugation of the Delos robots is deplorable because, after all, aren’t they human too (it asks, before slaughtering a few dozen security guards)? On the other hand, the show is now centered around a conflict among three robots over control of a fourth robot who is God. So much of the dialogue of this season is devoted to the various robots elaborating on just how superior each of them is to us mere mortals that the only equivalence between them and their human counterparts is that all of their conversation is equally mechanical, whether they’re organic or not.

Despite everything, Westworld seems poised to turn away from both senseless spectacle and tired moralizing about robots (it’s been 38 years since Blade Runner came out, after all) to finally talk about something concrete. ”We’re not so different,” escaped robot Dolores says to construction worker Caleb in a trailer for a later episode – but I suspect Nolan and Joy will handle that subject matter with all of the subtlety and nuance of a Nebraska freshman hitting his roommate’s bong for the first time (Did you know that “robot” comes from the Russian word for worker? Crazy, right?). This exploration of the exploitation of labor is, after all, coming from the same writers who brought you cyber-communion wafers, “Robots don’t kill people, people kill people,” and (I can’t stress this enough) Crime Coins.

Westworld airs Sunday nights at 9 pm on HBO and is available to stream on HBOGo.

One Comment

Stubbs died in season 2? When did this happen?