Hearing someone tell you about a dream they had can make your eyes glaze over. It could be because dreams follow their own logic, unique to each of us. Dreams can feel specific, urgent and compelling after we’ve experienced them, but vague, meandering and uninteresting in the retelling.

Cartoonist Roz Chast understands this completely—but she still wants to tell you about her dreams anyway. Her latest book, “I Must Be Dreaming,” mines her lifelong interest. She writes, “I’m fascinated and thrilled by that moment when one’s thoughts stop being everyday thoughts and…fly away.”

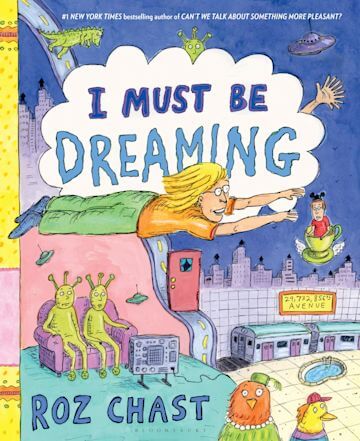

The beloved New Yorker magazine cartoonist and New York Times-bestselling author has made a name for herself with her crabby, neurotic and anxiety-ridden observations about what’s weird, wonderful and ridiculous about urban life. In “I Must Be Dreaming,” she tackles the surreal inner world we all uniquely experience with her signature kooky humor.

What are dreams? Chast wonders. A way for our unconscious to convey important messages to our waking selves? A chance to tap into the collective unconscious, the hive mind? Or something disturbing we try to rationalize as nonsense? (Think of how, in Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol,” Ebeneezer Scrooge, visited by the ghost of his old business partner, Jacob Marley, tried to dismiss him as a bad dream: “You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of an underdone potato. There’s more of gravy than of grave about you, whatever you are!”) Are dreams messages from the beyond, predictors of the future, or just a way for us to creatively solve problems?

Chast doesn’t have the answer—she doesn’t think anyone does. Here’s what she does know: None of us has ever had a dream in which we didn’t appear or weren’t central to what was happening. (Even as an observer in dreamland, we’re less narrator, more main character.)

Chast has a near-lifelong habit of keeping a legal pad and pen beside her bed to jot down her dreams. Sometimes, she gets “a very specific, yet very idiotic, cartoon idea” (which The New Yorker has sometimes rejected). Yet Chast continues to scribble.

Chast illustrates all this in her signature scratchy style, depicting herself in glasses and a bob haircut, frumpily dressed. Throughout the full-colored illustrations, longtime fans will recognize familiar Chast motifs: wallpapered rooms, rotary telephones, printed aprons, and hats with flowers sprouting out of them.

Chast grounds the flightiness in “I Must Be Dreaming” with the wisdom of philosophers and poets. “A Brief Tour Through Dream-Theory Land” enlists the insights of psychologists Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, the mystic teachings of the Kabbalah (which Chast says indicates that dreams refresh the soul), and science. She tacks this section on to the end, but I would’ve put it at the beginning because it gives people more points of entry into the subject beyond the rectangular shape of Chast’s pillow. (If you get this book, trust me: Read this part first.)

Do dreams serve a purpose? Who cares? Chast seems to say. Dreams are free, everyone can have them, and if not always entertaining, they are always surprising. That said, you just might want to keep yours to yourself.