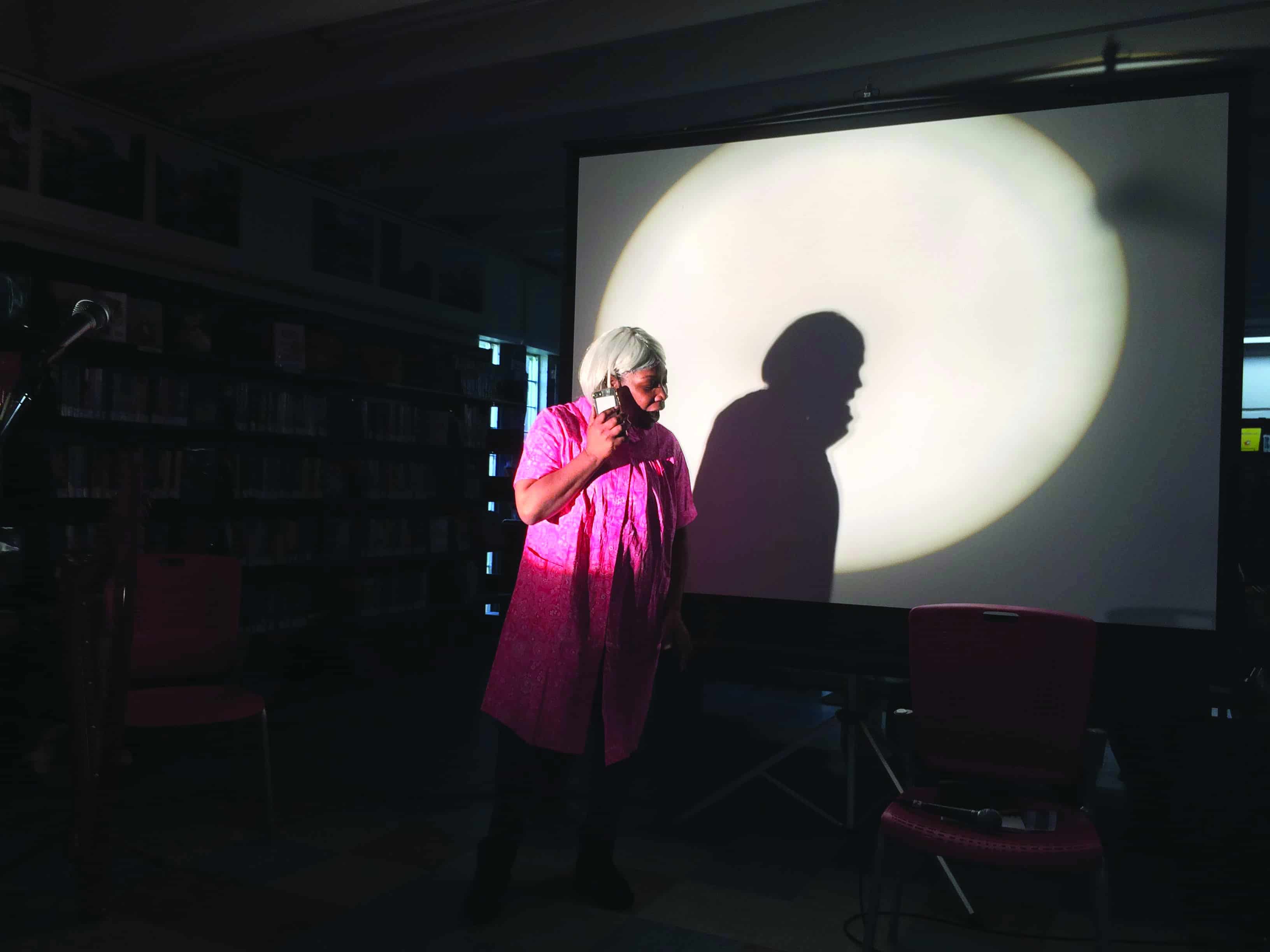

On October 20, the Red Hook Library hosted a free performance of “Soft” by the Theater of the Liberated. Directed by Carolyn Ferguson, a resident of the Gowanus Houses, the play dramatized the administrative labyrinth that NYCHA tenants have to navigate when they request repairs for their apartments.

Last year, the nonprofit Hester Street organized an arts forum called Making Gowanus, and out of this grew the Theater of the Liberated, which artist-activist Imani Gayle Gillison created as a means to promote the grassroots movement to reopen the Gowanus Houses Community Center, closed for more than a decade. “Soft,” which Gayle Gillison wrote, premiered on August 30, 2017, at Fort Greene’s BRIC House following rehearsals that took place at the aforementioned community center despite its official closure; that October, Mayor de Blasio promised publicly to reopen the center permanently, though, so far, it remains shuttered. For its second production, the Theater of the Liberated plans to parcel out the show across New York City, staging portions of the play in various communities. “When you do the performance, you don’t have to do it exactly as it’s written because the parts are more tailored toward the individual,” Ferguson said.

For Red Hook, she chose a segment titled “Gotta Put in a Ticket,” in which, under Gayle Gillison’s direction, she starred last year, after starting out as a production assistant. As Ferguson recounts it, the Theater of the Liberated was “always a group project, and we were brainstorming on how we’re going to tell our stories, and [Gayle Gillison] asked us to name something you don’t like about NYCHA, so I said I don’t like when you call the call center and you say I need a repair done, and they send someone who just looks at the repair and then asks you to sign a ticket. It’s a whole big bureaucracy with that.” Gayle Gillison insisted that Ferguson take the lead role in the two-character sketch that followed, since she’d inspired the story.

This time around, with Ferguson directing, Lanown Faison of the Ingersoll Houses played the public housing tenant, and Lawrence Simmons of the Queensbridge Houses appeared as the maintenance worker. At the start of the play, Faison notices a leaky pipe in her bathroom and phones the NYCHA call center for help, summoning a worker to her door. As it turns out, his job is not to fix the problem but merely to verify its existence, thus allowing Faison to follow up with a second request for a plumber. The delay, however, compounds the problem, which ultimately demands both a wall repair and mold remediation for the floor, each requiring its own separate maintenance ticket. But, alas, not in that order: for safety, ordinary repairmen can’t enter the unit until a specialist has taken care of the mold, even as the tenant is expected to live with it every day. NYCHA residents are typically forced to skip work to wait on undertrained maintenance workers who frequently fail to address the reported issue adequately, and small repair jobs can stretch on for months or even years.

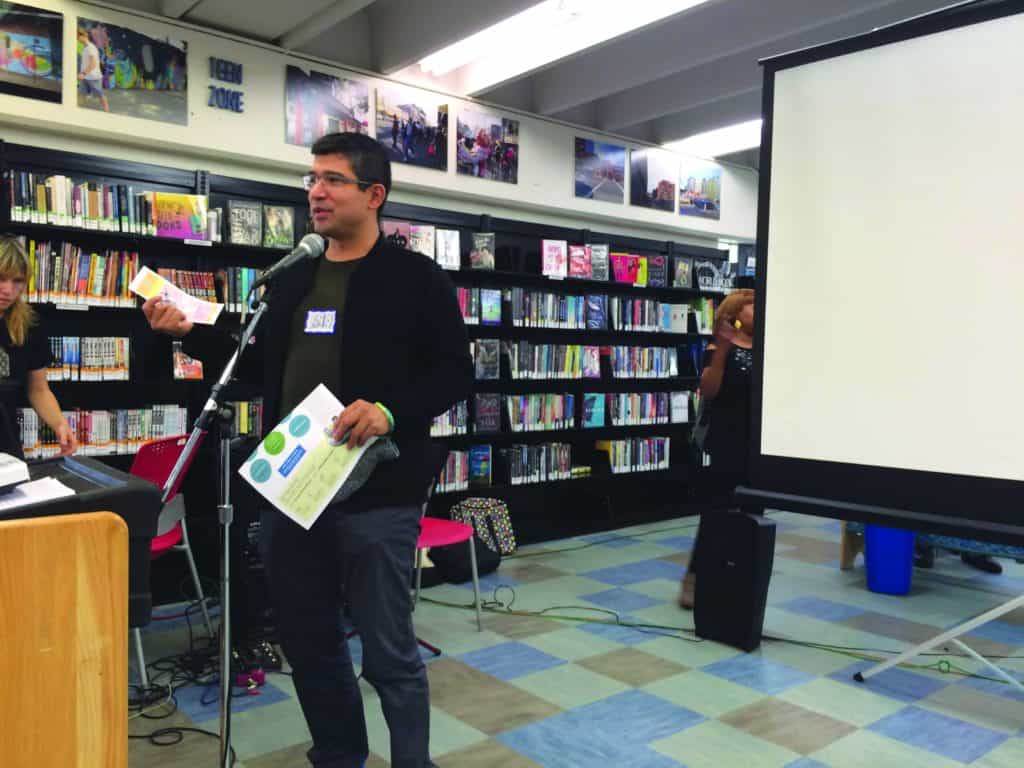

Before the play, City Councilman Carlos Menchaca gave a brief address, in which he acknowledged the “incredible frustration” experienced by NYCHA residents when their maintenance requests go unheard but also celebrated “the empowerment that comes from organizing around that.” Karen Blondel – representing the Fifth Avenue Committee’s environmental initiative Turning the Tide, one of the show’s several sponsors (which also included the Brooklyn Arts Council, the NOCD-NY, Arts Gowanus, and the Gowanus Neighborhood Coalition for Justice) – spoke between acts, advocating for a system in which public housing residents would be able to go outside NYCHA to report their complaints.

Referring to the events of the play, Blondel observed, “Most of you don’t have to experience that if you don’t live in public housing, because you get to call 311. And when you call 311, they send out a certified building inspector to you, and that person writes up violations on your building, and your building owner is then given a specific amount of time to remediate those problems. It’s really unfair that we pay taxes in public housing and we don’t have a right to call 311 like you do.”

After the performance, Blondel offered a short verbal quiz for the audience, covering material from the play and from the Where We Live NYC workshop (part of “a process to promote fair housing, confront segregation, and take action to advance opportunity for all”) that she’d held at the library in the preceding hours for much of the same crowd. She handed out gift cards for correct answers. Red Hook resident Ashley Taylor, who had played the harp as the stage was set up, contributed a voucher for a free movie night at the private, 15-person screening room at RE:GEN:CY, the new event space that she co-owns on Commerce Street, and Jeannine Bardo, co-founder of the climate change awareness project Ark for the Arts, won the ensuing raffle.