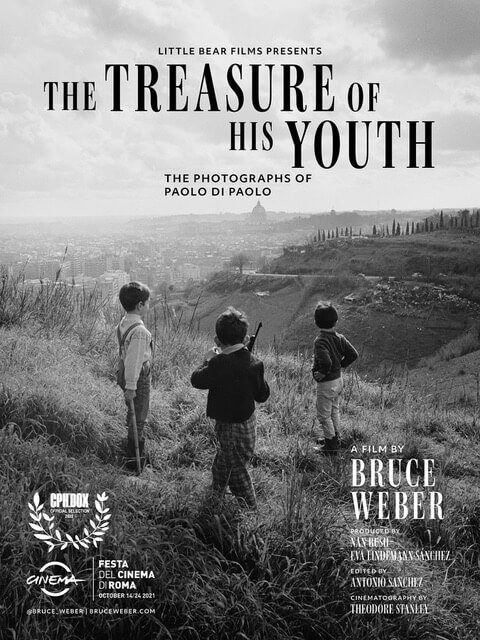

What compels a master of his craft — at the height of his powers — to walk away, to say “finito”? That question haunts Bruce Weber’s documentary The Treasure of His Youth: The Photographs of Paolo Di Paolo, and it’s one the filmmaker spends 105 minutes not answering.

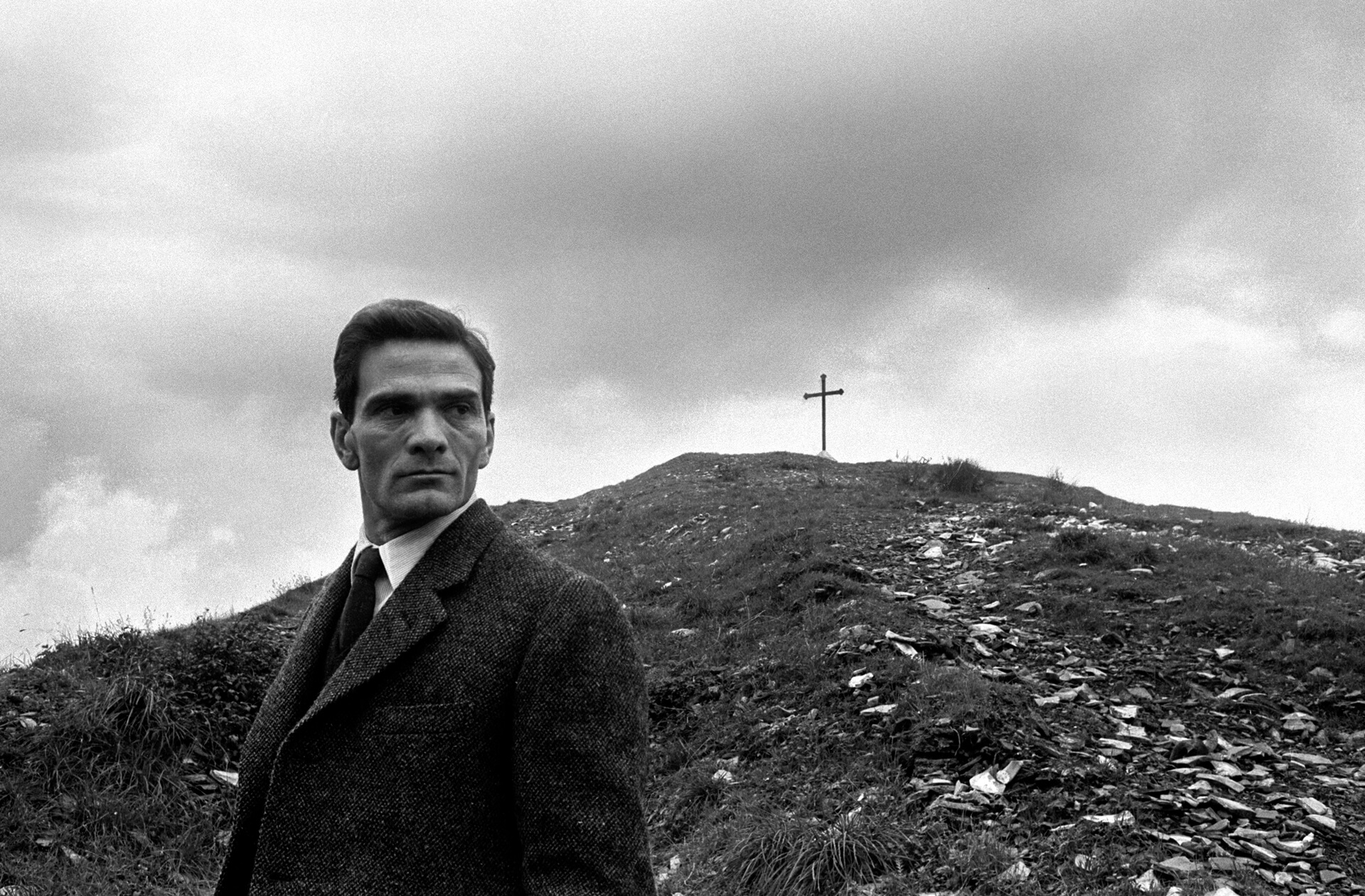

It’s easy to be taken in by the film because it’s so gorgeous. Di Paolo spent 15 years shooting strikingly beautiful and achingly empathetic neorealist images of postwar Italy and the dolce vita film scene of the 1950s and ‘60s. His photos of rural communities and urban destitution are documentaries unto themselves, testifying that the people in his frame were here, that they existed. Likewise, shots of stars like Marcello Mastroianni and Anna Magnani and directors like Pier Paolo Pasolini are more vivacious and humane than candid behind-the-scenes snaps. They’re evidence of the mutual trust and intimacy between photographer and subject, the former granted entry not into their trailers or dressing rooms but their homes and interior selves. One image in particular, of Mastroianni sitting alone in a smoky, shadowy cafe, is breathtaking, shattering the celebrity myth and while confronting the postwar existentialism that gripped everyone from cinema megastars to anonymous farmers.

After living under Mussolini’s suffocating Fascist regime, where “we couldn’t see anything beyond this cloud,” as Di Paolo describes it, the fall of the regime sent the then-18-year-old striver, like others of his generation, to see what existed beyond the limits of Larino, his hometown in the south of Italy. “We went everywhere with our imaginations,” he says, and it shows in his images, which were published in illustrated magazines Il Mondo and Tempo Illustrato. But when the publications shifted in the mid-’60s with the rise of television, they deemphasized photography — or at least the kind he practiced; they started looking for more gossipy paparazzi-style material — and Di Paolo chose to retire. He was barely 40, but, he says, “I preferred stopping rather than observing my own demise.”

That’s an easy explanation, and one that makes some kind of surface sense. But Di Paolo didn’t just retire. He stopped taking photos. He boxed up and sent to the basement his negatives, prints, and camera. He never discussed his career as a photographer, with his daughter or anyone else. He fashioned himself into a local historian of the carabinieri. His legacy, lying dormant, was forgotten. It was only after crossing paths at a flea market and making friends with a photo dealer decades later that he began opening up about his previous life.

That dealer is how Weber found Di Paolo, serendipitously discovering his photographs at the dealer’s shop while strolling through Rome “a couple years ago.” He was instantly smitten — “It was like falling into a forgotten world,” Weber says — and it’s easy to see why. And thus we have The Treasure of His Youth, tracking Di Paolo’s journey, which includes a long-overdue retrospective, his first, in 2019 and, miraculously, a commission to shoot a Valentino couture show in 2020. (Designer Pierpaolo Piccioli created a collection inspired by a fashion image taken by Di Paolo in the ‘60s.) We spend a lot of time with Di Paolo and his daughter, the caretaker of his legacy and a driving force behind the film, and being in his presence is warm and uncanny. He tells great stories — the one about being cured of a childhood illness with regular red-wine baths is incredible — and he practices the elegant precision of a worldly nonagenarian who’s constantly bemused by his second brush with fame. But he’s also undeniably Italian of the kind familiar to so many Italian Americans. Looking at Di Paolo in his younger days, it’s impossible not to see flecks of my grandfather, father, uncle, myself. (My family is from Pizzoferrato, close enough to Larino that the similarities feel more than coincidental.) It makes the experience of being with Di Paolo and hearing his memories so powerful — more than even the images.

It’s also why The Treasure of His Youth is so frustrating. For some reason, Weber lays down a parallel story of his infatuation with and love of Italy, which is neither interesting nor all that relevant. He tries to be cute in the construction of the film, presenting everything in black-and-white except for interstitial footage shot to look like it’s on 8mm film and then manipulated to be washed out and seemingly jumping out of the projector gate. (It’s all digital.) He drops in a montage, about halfway through as a kind of intermission, of scenes from Italian movies of the ‘50s and ’60s set to the Barry White track “Volare” — an embarrassing, inexplicable diversion that makes clear he’d rather be making a movie about la dolce vita cinema.

Worst of all, Weber is incurious. After the majestic coda of the Valentino show, Weber can’t let Di Paolo and his family have the last word. With only a couple minutes left in the film, he pops in with his languid, monotonous voiceover asking what everyone watching the film has been wondering: Artists lose confidence, but they rarely just quit. So why did Paolo Di Paolo? Great question! It’s really too bad he couldn’t find time over the course of this enterprise to tug at that thread.

Though, maybe he can’t — or, at least, not anymore. Weber, a photographer, dips into documentaries from time to time, and his 1988 Chet Baker film, Let’s Get Lost, has a fairly good reputation. So what went wrong here? He doesn’t speak Italian, relying instead on a friend to be his translator, so it could be that this lingual gap swallowed introspection and investigation. We see one moment of his translator friend getting deep with Di Paolo about a photograph, in Italian, so if we’re giving Weber the benefit of the doubt, there’s evidence that he was just in over his head. A less generous reading is that it’s a self-centered film about one man’s love of Italy and Italian cinema with a short-film celebration of this exquisite photographer peppered throughout.

In either case, that The Treasure of His Youth isn’t structured around getting at an answer to the core mystery of Di Paolo’s art is insurmountable. Yes, the images are gorgeous. It was love at first sight for me, too, just seeing the film advertised by Film Forum, where it screened in December. (It’s currently not streaming anywhere, but that may change in the months ahead.) But there is a story here, one that’s nodded at as we pass it by. Di Paolo’s experiences, memories, and photographs are wonderful — and important to telling that story fully. But without a true interrogation of why he quit at the center, everything shoots off in a million directions, tearing the veneer off the documentary to reveal little beneath the photography.

But, oh, what photography! In that, I suppose, Weber deserves credit. He’s bringing Paolo Di Paolo’s images and career to wider attention — particularly in the U.S., and more than likely in Italy, too — and the photographer and his work make the film worth the time. It’s just too bad someone like Weber, who knows the value of making every shot count, wastes this one.