Bang! – The Unstoppable Force Meets the Immovable Object

From Oil City Confidential

I’m listening to the latest Wilko Johnson record called Blow Your Mind. A few years before that, I listened a lot to his previous album Going Back Home, a joint venture with Roger Daltrey, The Who singer. And way before that, I listened to his various Wilko Johnson Band efforts, the records made when he was a member of Ian Drury’s Blockheads, and his own outfit called The Solid Senders, going all the way back to 1977. But I started my Wilko listening journey before that even with the band Dr. Feelgood. So that’s where I’ll begin.

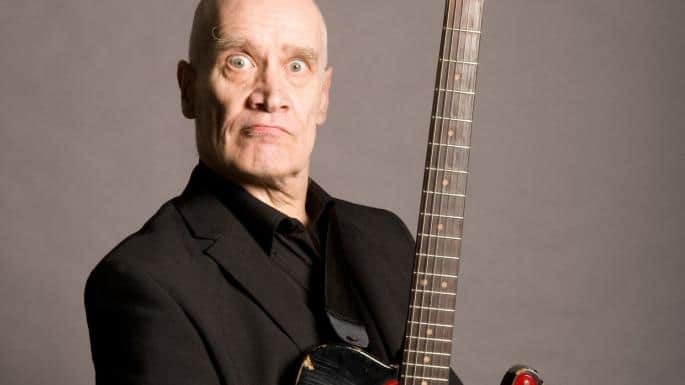

Wilko Johnson is an English electric guitarist and a singer. He performs edgy rock and roll. Most of his songs are his own creations. He plays his instrument without a pick. Wilko’s major influences musicianship-wise were Bo Diddley and Mick Green. You probably know who the former is. The latter was the guitar player for a British band called Johnny Kidd and the Pirates. They had a hit song called “Shakin’ All Over.”

Around 1971, Wilko Johnson teamed up with some neighborhood pals who were toying with the idea of forming a musical group. That neighborhood is Canvey Island, Essex. It is on the Thames River estuary, an off-the-beaten track wasteland then, southeast of London. Canvey Island was a holiday resort popular in the 1950s amongst London’s East Enders, mostly working people, the proverbial have-nots. It was a Redneck Riviera of sorts. It suffered a devastating flood in 1953. During Wilko’s formative years, Canvey Island was all busted up and broken, reminiscent of Bruce Springsteen’s Asbury Park after its demise as a carnival seaside town. Large oceangoing freighters and tanker ships were piloted up and down the channel. A still functioning oil and gas refinery with storage tanks stood across the creek. Its flare stacks burned night and day. If you would carry on walking east through the mud flats and they miraculously formed a bridge, you would wind up in Belgium. This is where Wilko and his bandmates grew up.

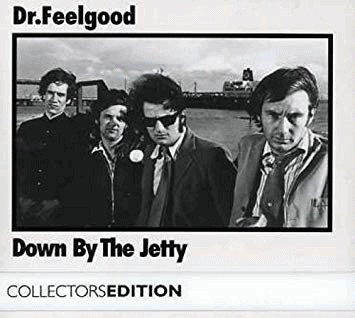

They called themselves Dr. Feelgood. They played a hybrid brand of rhythm and blues with mucho gusto, replete with songs from the likes of Chuck Berry, Lieber and Stoller (especially Riot in Cell Bock Number Nine), Muddy Waters, Rufus Thomas, and their own Wilko-penned songbooks. Dr. Feelgood arrived at the time of the Pub Rock movement, an up-from-the-bottom reaction to prog rock and the over-excessive production afforded bands whose members usually had double-barreled names like St. John. The original Dr. Feelgood lineup was Lee Brilleaux, the Big Figure, John B. Sparks and Wilko Johnson. The band all wore suits, the kind that locals referred to as “bastard suits” (wide lapels and flared trousers). One commentator of that period described them as a bunch of characters who might have come from “an unsavory faction of the army.” They could have easily been mistaken for English gangsters, stick-up artists or smash and grabbers, genuine spivs. But instead they were rock and rollers.

Dr. Feelgood was a mesmerizing band and they took the London club and pub circuit by storm. Joe Strummer of the Clash recalls them as “like a fucking machine.” They sweated their way into the hearts of a disaffected young hungry audience, one that felt abandoned by the sheer pomposity and non-accessibility of what surrounded them. No future indeed. Without Dr. Feelgood, there might not have been the Punks, who came soon thereafter and made a living out of rejecting the usual. The first three Dr. Feelgood albums, Down by the Jetty, Malpractice and Stupidity are gems that belong in any serious collection. Dr. Feelgood were gangsters all right, but of the Johnny Guitar Watson variety. They were Gangsters of Love.

Julien Temple, the English documentary filmmaker, made a trilogy of movies about British rock and roll, namely The Filth and the Fury (about The Sex Pistols), The Future is Unwritten (about Joe Strummer and the Clash), and the final one Oil City Confidential (about Dr. Feelgood). Canvey Island features prominently in Oil City Confidential. I recently watched it again to brush up for this article. What stands out in the film, which is a vivid portrayal of that time, of those particular individuals, and of that place, is how much Canvey Island then resembled the Red Hook, Brooklyn, that I first laid eyes upon in the late 1970s.

That was during the lengthy in-between period for Red Hook, when the working harbor and dockside industry had turned into a rust belt. This was before a new generation with seemingly loads of money saw Red Hook as a real estate investment and an opportunity to transform the neighborhood to better serve their interests. It was before IKEA, Fairway, ferry boats to and from Manhattan, and the cruise ship terminal. Red Hook was pretty much a commercially derelict area then, with corner bars, diners and the odd bodega hanging on. Residents were longtime homeowners who lived where their parents used to live, some bohemians and, of course, the people in the housing projects. They are still there. The mud channels were all churned up, abandoned boats lay high and dry atop them, and empty warehouses and old railway bogey wagons spoke of a different era, one that had gone the way of the buffalo. To borrow from Julien Temple, “there was an underlying sense of violence and a lot of alcohol.” He might as well have been talking about Red Hook, not Canvey Island. Like Canvey Island, Red Hook had one way in. You had to use the same way in to get out.

In Oil City Confidential, Wilko and the other band members fondly refer to Canvey Island as the Thames Delta, a clever play on the Mississippi Delta, showing respect for the music created in that part of America. This is why I wanted to write briefly about Wilko Johnson and Dr. Feelgood. Out of the most unlikely circumstances, a force can be unleashed that can capture the mood and light a spark of hope amid some desperation. Bruce Springsteen proved this, so did Muddy Waters, and so did Dr. Feelgood. Red Hook might not have produced its own Dr. Feelgood but it sure used to look like it should have.

Finally, Wilko Johnson is not going away in a hurry. About seven years ago, he was diagnosed with a near fatal form of stomach cancer. He had an almost three-kilogram tumor removed, survived, and is still hammering away. And while my knowledge of Game of Thrones can be written on the head of a pin with ample room left over for the Lord’s Prayer, I have been told that he acted the role of the executioner early on in the television series. Treat yourselves and give Wilko Johnson a listen. He’s earned it and you will not feel shortchanged but rather enriched instead. After all, he could have hailed from Red Hook.

All of the seminal Dr. Feelgood records and the most recent Wilko Johnson ones too are available for purchase on the internet, as well as the film Oil City Confidential.