I was introduced to George “Crime79” Ibañez by my friend, and George’s fellow graffiti legend, Louie “KR.ONE” Gasparro.

George and I spoke on the phone and then agreed to meet in Long Island City, near where I grew up. When I stopped by his office on 23rd street, under the 7 Train truss, I couldn’t believe how much that area of Long Island City has changed. When I was a kid, there were prostitutes, pimps and drug dealers trafficking those blocks. With sometimes only a single factory on a street, there was literally nothing else going on there after dark. If you killed someone and dumped their body there, it wouldn’t be found out until the next day.

But 23rd street is fancy now. The storefronts are polished. Across from George’s office entrance is a majestic skyline, second only to Manhattan in NYC.

I sat down with George in his office to talk about his career and work.

[slideshow_deploy id=’14756′]

Where did you grow up?

East New York, Brooklyn.

You call yourself a painter? Other graffiti artists, like Al Diaz “SAMO@”, call themselves writers.

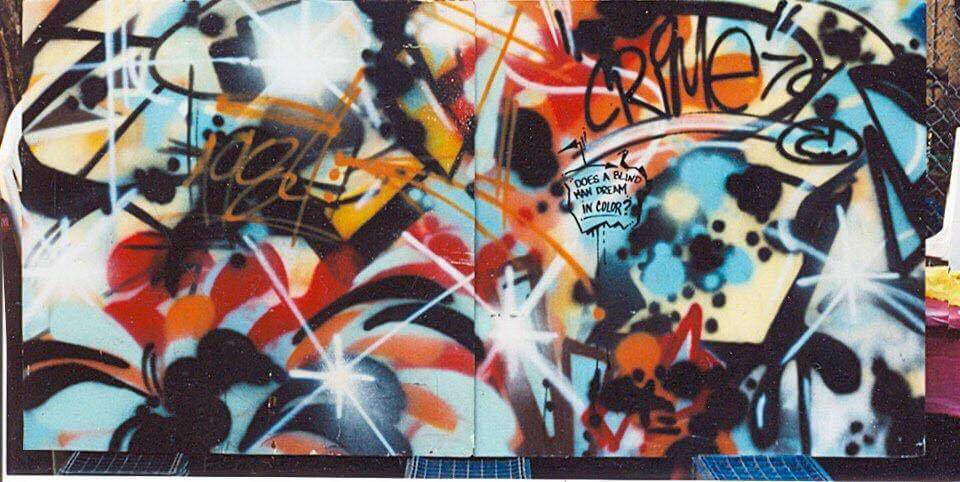

There are about four to five generations of graffiti artists. Al Diaz was a first-generation graffiti artist. Back then, they were wall writers, and subway writers. As graffiti evolved, the paintings became more elaborate. During my era, 79-85, was what some have called the golden era of graffiti. The images were stylistic and colorful. During this time, we started being more involved in the art gallery scene.

What kind of pieces did people paint?

There are three kinds of things you could do. With Subway art, you can do inside: writing on the inside of the train. Or you can paint on the outside and do throw-ups, bubble like tags of your graffiti name which are done quickly, thus giving you the opportunity to do many of them and get your name noticed a lot. If you get a train in the trainyard you have more time and can create stylistic pieces on the outside – more elaborate.

Is that in one night?

Yes, one day, or night. One session. In the trainyard or in the tunnel. You learn the schedules. Between 6AM-9AM all the trains are out. It’s rush hour. Then trains get put in the trainyard during the day. From 4PM-7PM all trains are out again. After 7PM they start parking trains. Graffiti artists knew where they were parked. During weekends, most trains are parked. Once you learn the schedules, you keep the details to yourself. If you found a tunnel, you never told anyone where you painted. We used to say they’ll make it hot for you. Maybe the cops will scour it now. Not to mention that you could get your ass kicked in the train yards. I went in, did my business, and went out. Some of the guys went in and vandalized or robbed you. They’d take your paint, your money. Whatever they could get. You had to paint in your approved area. I couldn’t walk into places like Woodhaven, Queens. Not just the trainyard, but the neighborhoods themselves. I used to paint on Metropolitan Avenue on the M line. That yard was controlled by Siko, an Italian American kid. I couldn’t have just waltzed into that yard. There were a lot of other kids from the neighborhood that would stroll into the yard. You needed to have cover. Graffiti artists weren’t necessarily racist. The question was: do you write? If you do, we can hang out.

How did you meet Siko?

I got to meet him through another graffiti writer called Risco. I met Risco on the train platform, while I was benching. Benching is when graffiti artists sit on benches and watch the trains go by. You watch your own work on the trains, check out other people’s work, scope things out, take pictures. Just like Risco took me around where I wouldn’t have been allowed, I took him to places deep in Brooklyn, where he wouldn’t have been allowed.

When did you start writing on trains?

I started writing graffiti in 1977. I wrote around the neighborhood on walls, handball courts and a lot of paper. Every graffiti writer starts earlier, begins practicing before they hit the subways. Then someone says wanna go paint trains?

Why the name Crime79?

What attracted me to graffiti were names like HULK and MURDER1. My mind would be like, what does this guy look like? You see their names all over the place. I wanted to create a name that had shock and awe. The fact is the real reasons I got into graffiti have a lot to do with my father who left Cuba as a young child. My father was a revolutionary and bestowed upon me a revolutionary fever. He believed, as I do, that wealth should be spread. That it shouldn’t just be the rich that get all the benefits. This translated into my work. My paintings weren’t just vandalistic. I did paintings with poems. One of the most famous was in the book Subway Graffiti. You open the first page and there’s my poem dedicated to those who run from the law to express their art. I was always pleased that when a train hit the station during rush hour, they were going to see not only a beautiful image, but they were going to see my poem.

Do you remember the poem?

“Dedicated to those who run from the law to express their art…… Keep Runin.”!!!

How has being from East New York impacted your work?

Looking back at it now, I think that I did graffiti because it was a cry for help. East New York was tough. When I walked out that door, everybody, and I mean everybody, was always looking to challenge you. You had to always watch your back. Seeing murders. Violence. I needed to express myself. Maybe if there was a city or federal program where I was invited to paint, I would have gone that path. Or if the neighborhood had a swimming pool, some kind of social uplift, it would have decreased the crime rate. I had nowhere else to release the energy. We were left to our own devices. All of this impacted me, how I painted, the name that I chose, which, at the time, was a form of armor. But I didn’t know it then.

Have you had to defend your name?

That was the worst thing about the name Crime79. As I painted more and more, people wanted to try me out. In 1982, At the height of my writing career, I tended to paint by myself or with very few people.

What inspired you to become involved in graffiti?

I lived in a neighborhood where I would see writers hanging out when I was a kid. I would look at the way that they would be respected. Even at a time when New York was flourishing with gangs. Gangs would respect the writers for being renegades. Growing up in my neighborhood I would see writers hanging out in Highland Park handball courts. People like DIKE, SID THE KID, JESTER, TO TOP aka MICKEY 729, HULK. I didn’t know them, but they would be pointed out by people. They created somewhat of a secret society that only certain members knew about. I felt that I was part of that secret society when I would look up and see the train rumble by on the el [elevated train] and knew who did that tag.

How has your formal training influenced your work?

When I went to Franklin K. Lane High School in Brooklyn, a few teachers pulled me aside and said, “what you’re doing some adults are not even doing.” They saw that my work involved composition. Some teachers said “you gotta do something with your art. That’s your ticket out of here. Take it to the next level.” A few teachers took me under their wings, took me to places like the Art Students League. Another teacher took me to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Going to the Met really opened my eyes. I started thinking about what I was going to do after high school. On the advice of a guidance counselor, I studied graphic design at the School of Visual Arts. Ironically that was a struggle. Here I am doing murals, typography, shading (darks, highlights) since I’m thirteen or so and now I’m with people that are just starting out. I learned so much doing graffiti. You have to remember that we got our ideas from things like advertising, billboards, and cartoons. Think Batman: BAM ZOOM BANG. Or Brillo ads using traditional graphic design with arrows and cartoons. Teachers would say “do a logo” and mine would have a graffitiesque touch to it. Now this stuff is taught in schools. But we were way before our time. Very few artists are celebrated and collected in their time. I was frustrated and left the School of Visual Arts. In hindsight I should not have left. Although I was talented, the school would have refined me. Taught me how to better use the correct color palette, apply precision, perspective, and so forth. When I was younger, people that had that degree became my boss.

How did you break into the mainstream?

I developed a portfolio – no graffiti – and headed out to Madison Avenue. I pounded doors until I found a job. They paid me peanuts, but it was my foot in the door. I started out doing graphic design. Then I wanted more money. Someone told me that I should get into photography. I started doing special effects, composing images together. This was before photoshop. I did my work in the darkroom. Then the computer came. I learned Quark, Photoshop and, lo and behold, that’s how I built my business. One brick at a time. Today I’m a learner. I deprived myself as a kid, so now I’m thirsty.

What is something people would be surprised to know about you?

Corporate people don’t know about my graffiti background. In the corporate world you wanted to be taken seriously. There are different codes. It’s not that I hide it. I just don’t mix the worlds unless they happen to mix naturally.

Can you tell me about any future projects?

Three years ago, I embarked on the idea of writing a book. There have been a lot of books out there, many are titillating and sensational. Some end with the subjects incarcerated or dead. I wanted to write my story. I knew my story was different. A friend said to me that there’s no one that can write the Crime79 experience. And I thought that if I can reach one person to make a change in their life, that alone would be worth writing the book. After going to fifteen publishers, I decided to create my own self -publishing company. I learned how to use InDesign and other tools in the publishing business. I shot the photos, designed the book, and wrote the book. I’m a printer. That’s what I do. This is just another chapter in my life. I’m looking forward to it.

George “Crime79” Ibañez

https://www.crime79.com/index.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Ibanez

Mike Fiorito

www.mikefiorito.com

www.fallingfromtrees.info

https://www.pw.org/directory/writers/mike_fiorito