The idea of the “star,” a celebrated and famous performer, isn’t new in and of itself. It goes back at least to the career of pianist Franz Liszt, who in the mid-19th century caused such public sensations during his European tours that he begat a new word, “Lisztomania.” And before Lady Gaga and even Barbra Streisand, there was the first, 1937 version of A Star is Born, starring Janet Gaynor. We’ve had stars in popular culture even before there was anything identifiable as popular culture.

But the meaning and quality of the word has changed through the generations, and certainly stardom in the film/radio era is a very different thing than in Liszt’s, although Lisztomania is a phenomenon that continues. Like stars gradually coalescing and igniting out of scattered gasses, so has the meaning of stardom changed. The ingredients of Billie Holiday, Frank Sinatra, television, Top 40 radio, The Beatles, Andy Warhol, Elvis, Elizabeth Taylor, the Baby Boom, glossy magazines, MTV, Michael Jackson, Madonna, Kim Kardashian, and social media platforms mean that stardom in 2021 is very different from stardom in 1921. That difference is greatest in music, and because the idea of music is dominated by pop music, the stars have mostly been singers, and singers are different these days.

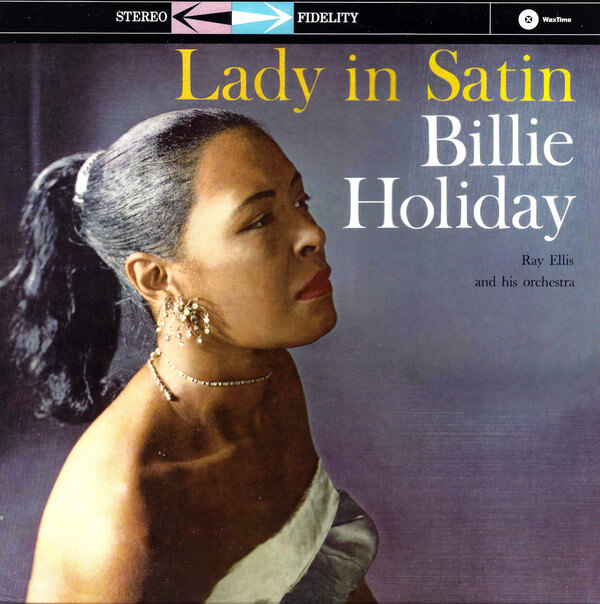

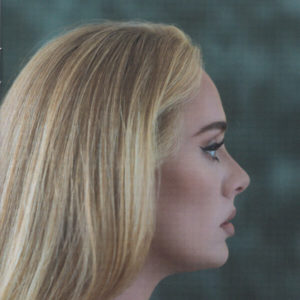

Music has changed, yes. One hundred or so years ago, after Louis Armstrong—who was a star—invented modern pop music (which he did), the singing stars were Bing Crosby, Holiday, Sinatra. They were greats and had styles that set them apart and had other musicians learning from them. Singers still dominate the scene today, across pop music and into what is called “melodic” hip hop, and two megastars in particular, Adele and Taylor Swift, have recent releases that have cemented their stature. But the music on Red (Taylor’s Version) or 30 is just not the same as what you’d hear on an album from Crosby or Holiday or Sinatra. It’s not about styles—those change superficially but except for modern production techniques and some rhythms that come out of contemporary Black music, things are not drastically different—it’s about subjects. It’s about songs.

When Swift or Adele sing, they are singing about themselves, they are the centers of their own universes, socially and musically. The songs and albums are about their relationships, their breakups, their heartaches, not about yours. This is not necessarily better or worse, that’s a matter of taste, but it is a different quality, and it’s that, stars expressing things about them-selves and not about much of anything outside themselves, that makes identification with them so unsettling. The joke in Spinal Tap, about “when you’ve loved and lost like Frank has,” then you’d appreciate the crooners, has become true in an odd way. Have the fans of Swift and Adele loved and lost like those two singers have? Maybe, but what matters is that those fans are on the singer’s teams, on their side, suiting up in the keyboard battles over reputation and status, who wronged whom, who’s a winner and who’s a loser. Not just fans, but stans. The songs aren’t the things—the songs on these albums are polished and well-made but not really memorable, except in the way that they cement the solidarity of the armies of fans—and the songs are a dis-tant second in importance to the singers.

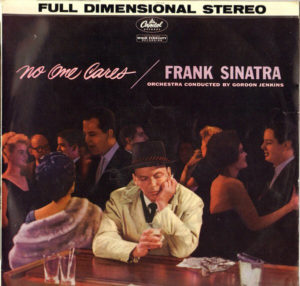

When Billie Holiday sang “All Of Me” or “Don’t Explain,” when Sinatra made Songs for Only the Lonely, or sat for the incredible picture on the cover of No One Cares, sitting alone at the bar, staring in desolation at his drink while the packed crowd around him enjoys itself, they were central figures but they were singing songs that reached outside themselves. Holiday sings “I,” but she’s not singing to Jake Gyllenhaal or John Meyer, she’s a woman singing to someone whom she loves but who is breaking her heart. Even if Holiday had a person in her head when singing, we don’t hear who that is. This is true for Sinatra too, he’s not singing from a metaphorical stage, he’s sitting next to you at the bar, and he’s never mentioning a name. They’re singing about their experiences with strong musical egos but transparent personal ones, the songs are there to tell the listener that we’re all in this together.

Adele sings about her divorce, and maybe that connects to the listener, but what she is saying is “listen to me tell you about my divorce.” When Sinatra sings, it’s about us, about how he, and we, have loved and lost. Sinatra was a star, Holiday was a star, but their stardom was not about anyone being on their sides, it was about how they were on our side, they were with us on the high and low, in good luck and beaten down, in and out of love. Both singers recorded the wonderful ballad, “What’s New,” with the agonizing line, “I haven’t changed / I still love you so”—no accusations, no blame, no righteousness, just a song about living with the experience of being in love, losing that, and still carrying the weight and tenderness of that feeling around. Because they were such wonderful artists, they made that real for anyone with that same experience, they articulated what it is the listener felt, they explained it to us, their fans.

That’s the generosity of a great artist. Swift and Adele sound great, but they don’t move me in anyway, they don’t have that generosity, the self-effacement to put their personality and experience entirely into their voices and sing to us as peers, rather than stand on stage as stars and have us admire them. What they are doing is so specific that it’s impossible to imagine them expressing anything other than the fallout of a standard heterosexual relationship—I can’t imagine “All Too Well” ending up in the context of an LGBTQ+ performance, and the covers of it by other singers heighten the oppressive blandness of the song.

Sinatra contributed lyrics to “I’m a Fool to Want You,” an American standard. The song comes out of his stormy relationship with Ava Gardner, but it’s so concentrated, elegant, and such a song about life—not his life, but everyone’s—that anyone can sing it. It’s on his classic album, Where Are You?, and it’s the first track on Holiday’s thrilling and harrowing Lady in Satin. There’s no scarf, there’s no sister’s house, there’s no drinking wine, there’s just “I” and “you,” and trying to let go and fighting memories. There’s only one Taylor Swift and one Adele, but we are all an “I” to ourselves and a “you” to someone else, and it’s not the stars that are the thing, but the songs.

Author

-

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/

View all posts

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/