I opened an old friend’s email the other day. It read, “That was a time it was…wasn’t it?” Attached was a copy of the Brooklyn DA’s felony complaint against David Berkowitz, sworn to by Detective John Falotico, dated August 11, 1977.

Back then, I was a Brooklyn probation officer again. My first go-round ended on July 1 of 1975, when 40,000 cops, firefighters, sanitation workers, teachers, and me got fired. We were not alone: between 1969 and 1976 NYC lost 600,000 jobs as employers relocated or went belly-up. Conversely, the population of African-Americans who had fled the Jim Crow South for a new life in the City rose from 460,000 in 1940 to 1.7 million in 1970, just as the unskilled jobs that had sustained generations of European immigrants before them evaporated. The City was broke.

But I was fortunate. A laid-off cop friend clued me to a job opening as a New York State inspector of adult homes. Alas, corruption was so rampant at that agency (deservedly long defunct), that one sleazy owner, five minutes into my recitation of his violations, expressed astonishment that I was not yet shaking him down. So, yeah, when the City offered me my job back in late 1976, I readily accepted.

I was bequeathed a caseload of 250 unattended felons, most of whom had been rampaging their way toward tabloid headlines as “unidentified perpetrators.” One of my charges, located in his immigrant mother’s tempest-tossed Pennsylvania Avenue apartment near the Belt Parkway, readily admitted he had never reported to the Probation Department, but seeing as how I had gone to the trouble of visiting him and such, why, he would certainly return the favor by dropping by my cubicle at 345 Adams Street on the approach to the Brooklyn Bridge.

His name was Charlie. A little chunky and on the short side, he had racked up multiple arrests for Grand Larceny Auto long before it became a video game, followed by commercial burglaries, an eventual felony conviction, some jail time, and a slot on my caseload at the age of 23. A Catholic grammar school graduate who had gone astray according to his mother (‘Twas a bad crowd he fell in with come high school, she explained with the slight trace of a Scots accent), Charlie was then working for a local handyman. He defended his prior thievery by concluding, in a peculiar manner on multiple occasions, “I was merely trying to escape the sewers of New York.”

Then in late April my supervisor, Bill Blasko, a beefy ex-Marine, convened a unit meeting in his cramped Adams Street office to discuss the .44 Caliber Killer, who’d been shooting young White people in Queens and the Bronx for the previous nine months. Blasko would often wander off on odd tangents, usually to complain about all the non-Marines who surrounded him, but this day he solemnly announced that the Killer, a White male, in his 20s, about five-foot-eight, had left a note for the police at the last murder scene, indicating he was Scottish with a father named Sam.

When Blasko ran out of stuff to yell about, I rushed back to my cubicle and read through the file. Bonnie Charlie’s father was named Joseph, not Sam. Thank you, Jesus! Still, Charlie was kind of odd, so in an abundance of caution, exercising situational awareness, yada, yada, I reached out to the Task Force—Operation Omega the PD called it—at the 109 Precinct in Flushing. Surprisingly, the Detective who took my report was enthusiastic. Charlie’s parochial school education was important, he explained, because the Killer’s note was grammatically correct with good penmanship and as fellow Catholics, we both knew the Nuns and Brothers drilled those skills into us with occasional smacks upside our skulls to assist their drilling.

But as the weeks passed, absent any feedback from Omega, whenever Charlie reported I had to press him for an answer to a standard condition of probation: “Were you questioned by law enforcement since your last report?” Charlie coolly responded each time, “Of course not,” seemingly offended I would ask such a dastardly question.

Then on June 5th, Jimmy Breslin’s Sunday column in the Daily News began with a letter he’d received from the .44 Caliber Killer: “Hello from the gutters of NYC…Hello from the sewers of NYC.”

OK, that’s interesting, I thought, the whole sewers thing. And the grammar and spelling were impeccable. However, Charlie could not be the Son of Sam, I assured myself, desperately trying to banish the thought of being featured in an upcoming Jimmy Breslin column. Why, he had a complete lack of violent crimes, almost an outstanding citizen, aside from, you know, his hundreds of burglaries and larcenies. And he was the Son of Joseph, not Sam. Case closed.

As June ended, the Killer struck for the seventh time, shooting teenagers parked in a car at 3:30 AM near Northern Boulevard in Bayside. Lovers’ Lanes were quickly depopulating as No-Tell Motels rejoiced. Around that time I recall having a beer in a Court Street bar with a couple of colleagues who were experiencing a rare prime-time-crime moment in which fellow Blacks were neither the perps or vics. Then, as if to punish such hubris, on Wednesday, July 13, 1977, at about 9:30 PM, the entire hot sweltering City went dark. In White Park Slope and Midwood, food stores gave out melting ice cream for free, while citizens directed traffic with flashlights. In Black Bushwick and Crown Heights, stores were looted and burned. Why? Reference the 2nd paragraph above and discuss amongst yourselves. Me? I got reacquainted with my caseload, many of whom were among the 3,000 arrested by the NYPD that night. Remarkably, Charlie somehow avoided getting nabbed.

Given the Violation of Probation proceedings I had to arrange, Son of Sam was the last thing on my mind. Until July 31. That’s when Stacy Moskowitz, 19, and Robert Violante, 20, were shot in the head after they got into their car at about 2:10 AM in Bath Beach. Moskowitz died while Violante lost most of his vision. It occurred in a deserted stretch alongside the Belt Parkway, the first .44 Caliber homicide in Brooklyn. Charlie lived near the Belt Parkway. Uh-oh.

Detectives working out of the old 10th Homicide Zone squad in the 60 Precinct on West 8th Street, a short walk from the Coney Island boardwalk, got busy – Ed Zigo and his partner John Longo had already been working some Sam leads. Now John Falotico, James Justis, and the rest of the squad joined in, led by Sergeant Jim Shea. But Detective Sergeant Joe Coffey from Project Omega had the best overview of all the details of the case. After arriving in the Coney Island squad room, Coffey reached out to the two uniformed officers from the adjoining 62 Precinct who patrolled the Bath Beach area that night. Had they written any parking summonses? No, Sarge, they said.

In fact, they had. The officers later claimed they had forgotten about a very important ticket in all the excitement, being the first to respond to the scene and all. Coffey, a legendary investigator and a straight shooter, wrote in a riveting 1992 memoir that the cops probably lied to him out of fear they’d be reamed for not spotting the Killer, so close in time and distance to the shooting.

Coffey thought their crucial parking ticket was turned in only after he grilled the officers. In any event, the officers didn’t walk it over to West 8th Street. They just stuffed it among all the rest of the tickets in their Precinct’s receptacle. (After Son of Sam was sentenced, the Police Commissioner, who never cared much for Detectives, insisted, much to Coffey’s disgust, that the two lying uniforms get gold shields anyway.)

Thankfully, a witness emerged four days after the shooting who remembered seeing patrol officers that same night, at 2:05 AM, place a summons on a car parked at a hydrant along the Belt Parkway at Bay 17th Street. Out walking her dog, she also saw a man walk past her, holding – halfway up his sleeve – what might have been a gun. Minutes later, as she got to her house, she heard shots ring out. Breslin subsequently reported the witness was an illegal alien who had hesitated to come forward for fear of deportation.

And so, a week after the Moskowitz homicide, Detectives followed the immigrant’s lead and found the summons amidst a mound of unsorted tickets in the basement of the 62 Precinct on Bath Avenue. It was issued to a 1970 Ford Galaxie. A DMV check traced the Galaxie to a five-foot-eight White male, age 24, David Berkowitz. A postal worker and Army vet, he lived in a 7th-floor apartment at 35 Pine Street in Yonkers with a nice view of the Hudson River. Berkowitz was one of the few White tenants—make of that what you will—and his apartment overlooked the backyard of Sam Carr, who had a daughter named Wheat and a Labrador named Harvey.

Wheat just happened to be working the dispatch desk at Yonkers PD when the call came from Brooklyn. Berkowitz was a possible witness to a homicide, Jim Justus explained, wanting to be put through to Yonkers’ Detectives. The dispatcher exploded, “Berkowitz? He shot Wheat, my father’s dog! The guy’s a nut!!”

The 10th Homicide Zone descended on Yonkers. Detectives Zigo and Longo spotted Berkowitz’s Galaxie parked on the street below his apartment house. Visible inside the car – amidst clothes, bottles, papers, and what-have-you, strewn hither and yon, was an Army duffel bag stenciled “D. BERKOWITZ” with the butt of a sub-machine gun sticking out. An envelope lay nearby with the distinctive, large, printing style of the Son of Sam. Breslin would later describe it this way: “The inside of his car looked like the inside of his head.” Project Omega reinforcements flooded in. A stake-out began while Zigo pursued an arrest warrant in the labyrinthine bowels of Westchester County’s criminal justice system.

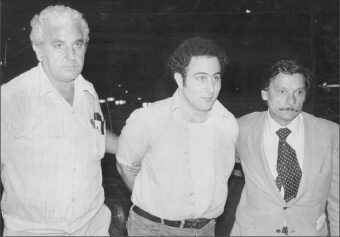

At about 10:00 PM Berkowitz approached the car holding a paper bag containing a .44 caliber revolver. His intention was to drive down to Riverdale to find his next victim, then wander out to the Hamptons, do the Hustle, and spray a disco dance floor with large caliber projectiles. As Berkowitz stepped into his Ford, Detective Falotico rushed forward and pointed his .38 caliber snub-nosed revolver at Berkowitz’s head. Longo and Gardella pointed their service revolvers from the passenger side while police cruisers rolled up behind them. Whereupon Berkowitz said, “Well, you got me.”

Questioned that night at Police Plaza by Coffey and others, Berkowitz confessed to all the shootings, claiming that Sam was a demonic spirit who spoke to him through Harvey, Sam Carr’s dog.

Obviously. So the .44 Caliber Killer wasn’t actually a son of Sam. But he wasn’t Scottish either. He was arraigned the next morning in Brooklyn Criminal Court for the Bath Beach shooting, with my old pal in attendance.

When Charlie reported to my cubicle a few days after the Berkowitz take-down, he complained mightily. “Some cop was hassling me last week, man, asking about my car.” I smiled knowingly, leaned forward, motioned Charlie to move closer, and confidentially whispered, “Don’t worry, I’ll take care of that for you.”

That Fall, I met Ed Zigo at the wedding of mutual law enforcement friends. I told him about Charlie. He laughed and said they’d been swamped with all sorts of leads. “There’s just no shortage of people in this City,” Zigo sighed, “whose neighbors think they’re serial killers.” Zigo served in the Pacific during WWII aboard the Battleship Missouri, launched from the Brooklyn Navy Yard in January 1944. He died in 2011. Falotico, a WWII Army vet, had passed away five years earlier. Coffey died in 2015 and Breslin followed him in 2017. As for Charlie, he became an electrician, got married, and moved to Florida. For all I know, he might be running for Congress. But I’ll give the last word to Jimmy Breslin: “Berkowitz is the only murderer I ever heard of who knew how to use a semicolon.”

POSTSCRIPT: In researching this piece, I learned that the Son of Sam’s biological father had the same first name as Charlie’s dad. Cue the wooh-wooh music, maestro.

2 Comments

Great stuff!

Nice story telling. Do you also write for the Prairie Home Companion? Ever live by Lake Wobegon. You remind me of the works of Great Garrison Keillor. Was he your father?

Garrison and now You are the best. Keep ‘em coming

Peter S