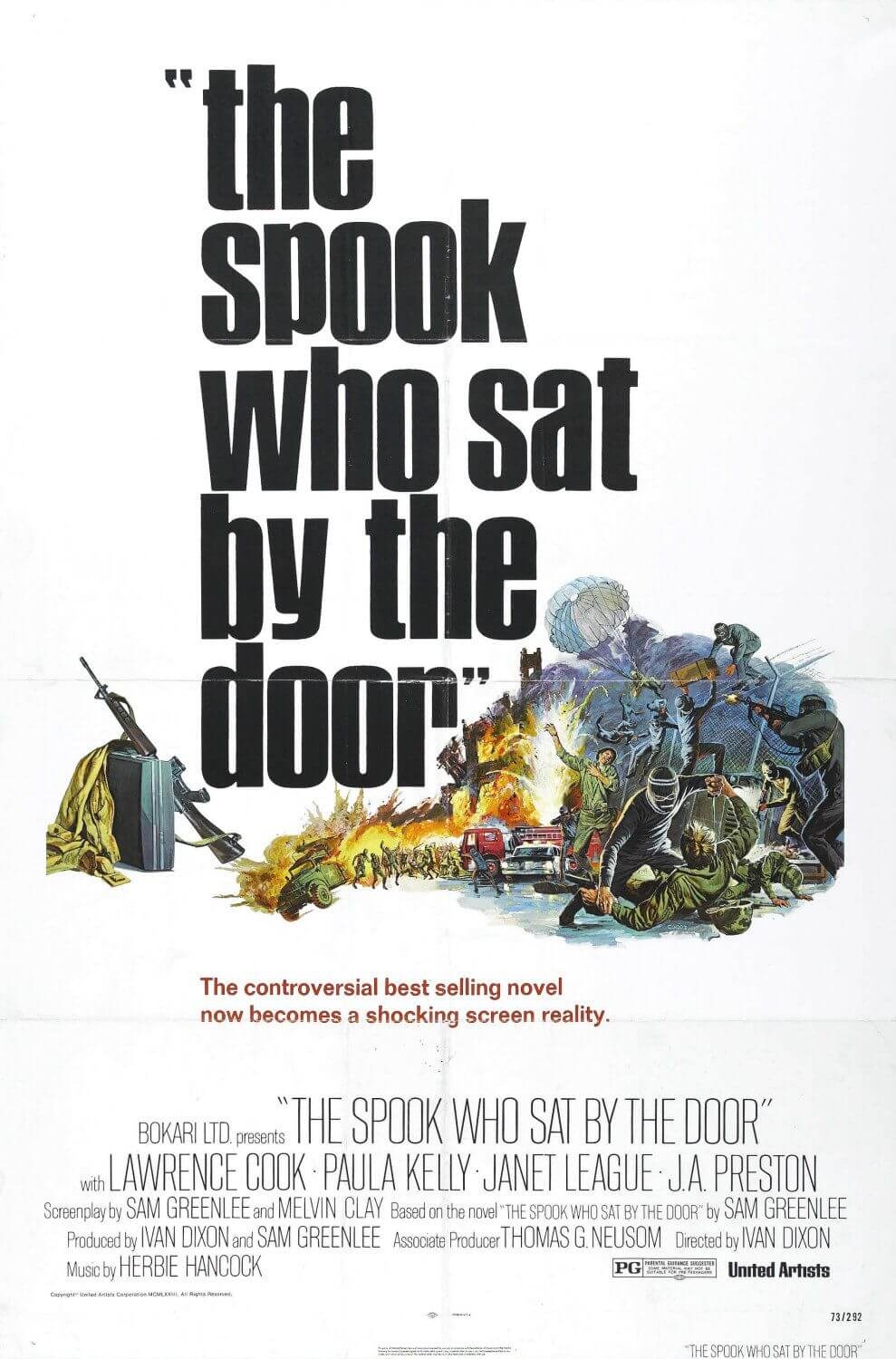

There’s an alternate universe where, after the 1973 release of The Spook Who Sat By the Door, director Ivan Dixon would have worked regularly in studio movies rather than be relegated to episodic TV journeyman. But that’s a universe where The Spook Who Sat By the Door — a singular movie about the CIA’s first Black operative, hired as token representation to show the agency is integrated then using his training to form and lead a guerrilla group of freedom fighters on Chicago’s South Side — was not pulled from theaters within days of its release and condemned as dangerous anti-American propaganda as sure to incite race riots as to doom our system of government.

Let’s be clear: Dixon’s adaptation of Sam Greenlee’s 1969 novel is dangerous, the way all necessary art is threatening to the status quo. But let’s also be clear about the status quo in 1969 and 1973: the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., Robert Kennedy, Malcolm X, and Chicago Black Panthers leader Fred Hampton; ghettos decimated by not-so-benign neglect and drugs; economic disempowerment; segregation; red lining; King’s non-violent resistance curdling into more militant Black Power movements; the Panthers; J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI domestic spy shop COINTELPRO; Kent State. That’s just for starters in this country. We can’t forget liberation movements in Africa and Asia that saw oppressed colonized peoples rise up to demand and seize freedom and self-determination.

In that environment, it’s understandable why those in power — in Hollywood and the government — would find The Spook Who Sat By the Door such a threat. Indeed, after it was pulled from theaters it was suppressed for 30 years, until Dixon’s personal print was used for a DVD release. For the first time in decades, the film was able to be seen widely, appreciated, and argued over. That led to it being added to the National Film Registry in 2012. And it got another boost recently thanks to a 4K restoration from the Library of Congress and Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation, which ran at BAM for a week in late August to packed theaters.

The Spook Who Sat By the Door was, and is, necessary and essential agit-prop filmmaking smuggled into the mainstream system via a Blaxpolitation disguise. No glorifying drug culture or pimps or gaudy consumption or fetishizing hood fantasies here. This is sly, angry, confident, provocative, audacious political cinema that upends assumptions of genre, of norms, of Hollywood to create a singular cinematic manifesto that reverberates, still, thanks to its past censorship and scandalously-still-relevant socioeconomic message.

From the start, Dixon masterfully weaponizes our expectations. The film begins by looking, sounding, and feeling like an episode of a police or espionage procedural. Sets feel stagy, dialogue is wooden, even the setup feels contrived. A senator fretting his reelection chances after a “law and order speech” didn’t go over well with his Black constituents suggests chastising the CIA for not being integrated. Next thing we know we’re in a gym full of Black men listening to CIA bureaucrats, followed by montages of hopeful agents learning how to build bombs, remotely blow up cars, use weapons. This is what everyone was so afraid of?

But it’s clear Dixon is doing something intentional when we realize we’re a third into the film and none of the CIA recruits with speaking roles are our main character, Dan Freeman (Cook). He’s part of the background, unseen and unremarked on by the CIA bosses, his class, even us. When we finally do meet him, he’s kind of nebbish, wearing glasses, buried in his books and notes, but with a controlled, just-under-the-surface rage. This sets Dan up as the kind of clandestine expert who would graduate into the CIA. But the withholding also puts us on notice that we can’t be passive viewers.

For five years, Dan plays the proscribed role of token diversity hire — running the copy room, personal assistant to the director — to the satisfaction of his superiors. Then he abruptly leaves for an executive role with a social worker agency in Chicago. Such is the CIA’s complete inability to imagine a Black man could actually use his training in the field that it lets Dan go with, ahem, token surveillance.

Foolish because Dan uses his high-paying, very public new job as a front to build his liberation army, turning a ragtag group of street hustlers and gangsters into a tight, disciplined fighting force. To show this process, Dixon recreates all the CIA training beats as DIY exercises in explosives, remote detonations, and tactical weapons. And when we hear the agency’s training on guerrilla tactics and organization come from the mouths of Dan’s army, it’s simultaneously hilarious, gratifying, and heart-stopping. So far, all this stuff has been academic. The CIA never let Dan put any of this knowledge to use, and even in Chicago it’s all been boot camp. But, clearly, things are about to get real.

When they do, the inciting incident is, unsurprisingly, the police killing an unarmed Black man. Up to now, The Spook Who Sat By the Door has bounced with a very ‘70s, very Blaxploitation Herbie Hancock score. But as the gathering of outraged Chicagoans boils over into a riot, Dixon drops the music and lets the cacophony of shouts, screams, sirens, helicopters, and dogs be the soundtrack. The scene is visceral and documentary-like. We’re in the crowd, on the ground, in the fight, jumping barricades. The scene draws on Watts and Selma as much as Haskell Wexler’s 1968 DNC-police-riot-set Medium Cool. It also points directly to Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing and Rodney King and the 1992 LA riots. And it stops us cold because it anticipates what we saw after the police murders of George Floyd, Breanna Taylor, Freddie Gray, and so many others.

As the film builds to this point, Dixon quietly pulls back from the ‘70s cop show aesthetic and moves toward a grittier war film look. And when we see the National Guard patrolling debris-strewn streets lined with burned out buildings, we know the fun and games are over. The Freedom Fighters, clad in black like the Viet Cong, get to work, abducting, drugging, then killing the National Guard commander; luring troops into ambushes; blowing up the mayor’s office; broadcasting propaganda and manifestos; activating other columns in large urban areas across America. Things get incredibly violent and intimate, to the point that I was shocked to learn it was rated PG.

But here, too, Dixon demonstrates his expertise. The ambushes, with their red explosions of gunfire illuminating the night from seemingly every direction, are brutal and beautiful; Freedom Fighter slipping across rooftops or through urban streets as sleekly and silently as stalking predators are ominous and elegant. When the Guard commander is abducted, the scene begins farcically: three revolutionaries infiltrate headquarters, slip into the commander’s office, and lurk as he watches a bad Western, rapt as a child in his undershirt. They take him to a pool hall, where they paint him in blackface and force him to drink acid-laced tea. Next we see him weaving through the streets in his t-shirt and underwear, blissed out on LSD and speaking happily about the people he just met. And then — CRACK! — he’s shot in the chest by a sniper. It’s a shocking exclamation point, and a point of no return.

The violence becomes the central preoccupation of white power structures and Black bourgeoisie. But Dan, who we see living in a well apportioned bachelor pad, wearing fine clothes, and driving a sleek red convertible, uses his Bond lifestyle as cover. He knows that materialism is meant to use a minority of the minority to convince everyone else that progress is possible. Rejecting the false promise of capitalist acquisition is as important to the revolution as the rejection of hatred. In one scene, Willie (David Lemieux, real life one-time Panther) says he hates the white man. “This is not about hating white folks,” Dan replies. “It’s about loving freedom enough to die or kill for it if necessary.”

It’s distinctions on top of distinctions, and they prove confusing to Dan’s friends, even Dan himself. They challenge the characters, their fight, and, in the end, us. Is there really no place for compromise? Is this an all-or-nothing battle? How does actual change happen without violence — against people, against systems, against ideas? There are no easy answers here, nor conclusions, and the film doesn’t end in any kind of tidy way. Rather, it concludes in a kind of montage of a roiling national war overlayed on a shot of Dan, wearing traditional African clothes, watching ruefully from his penthouse balcony.

(Anyone who has seen Fight Club will be familiar with this kind of open-ended sense of an ongoing violent overthrow of a broken socioeconomic system. Indeed, watching The Spook Who Sat By the Door, I was shocked by how much David Fincher’s millennial satire maps to this film, from broad ideas about who has been left behind by society to individual beats and scene constructions to how to even the scales. And both were similarly decried as dangerous and deviant and run out of theaters.)

Back in 1973, white LA Times film critic Kevin Thomas called the film “one of the most terrifying movies ever made,” reminiscent of white critics’ reception of Do the Right Thing in 1989. As if Black viewers can’t distinguish between art and real life. But it is undeniable that The Spook Who Sat By the Door is a threat to those whose power and wealth derive from subjugation. That of course puts it, forever, in the crosshairs of those who must maintain those systems. And it makes it required viewing for anyone held back, punished, demeaned, excluded, or restricted by them. Which is most of us — Black, white, and every color in between. Greenlee and Dixon knew, as King and Hampton did, that there is a class dimension to the struggle for liberation.

And as the assassinations of King and Hampton, and the attempted assassination of The Spook Who Sat By the Door, attests, acknowledging and calling attention to that superstructure of economic oppression is what makes a man, an idea, or a film truly dangerous.

One Comment

THE SPOOK WHO SAT BY THE DOOR was never banned; never suppressed. It played at movie theatres and drive-ins, on a regular basis and on a sporadic basis, for 11 years. It had its best run between 1973 and 1976; and then from 1977 onwards, it would play at a theatre or drive-in here and there throughout the United States until 1984. After that, an occasional screening at non-theatrical venues; including colleges and film festivals.