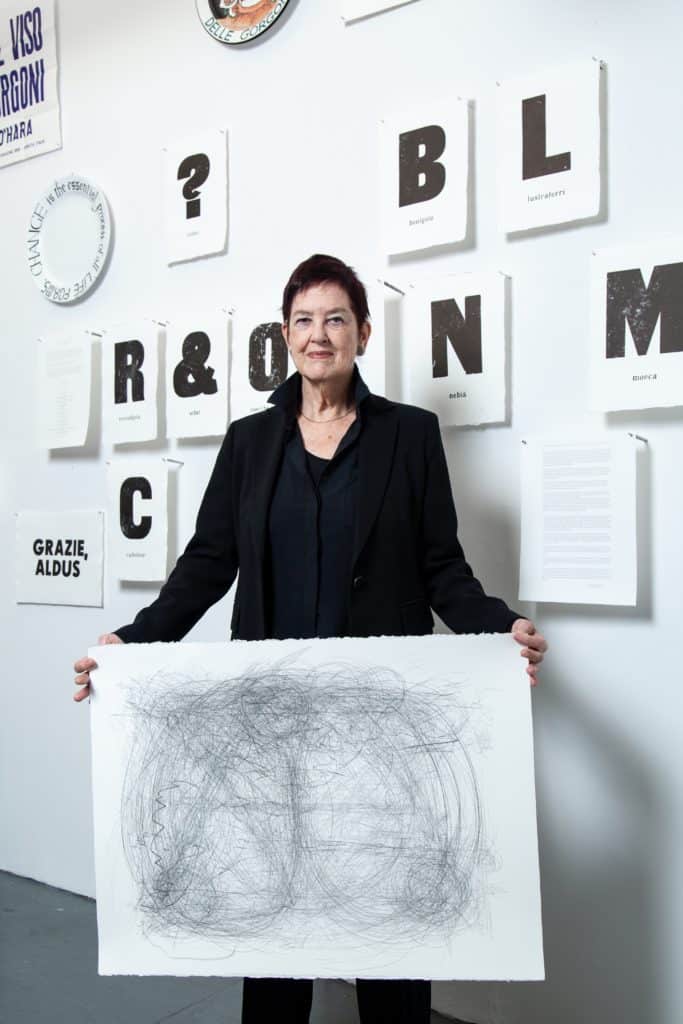

It’s hard to know where to start with the artist Morgan O’Hara. Since the late 70s, she’s drawn over 4,000 pieces from everyday life — dinner with some lively Italians, a Noam Chomsky lecture, a Taiwanese Lion Dance performance — works she calls “Live Transmission.” On first approach, you’ll see a condense fog of scribbles or a soft web of lines so threadbare to looks like lace. But picking a line (any line!) and following its curve and density, its meetings with the velocity of its neighbors, there’s the sensation of a time warp back to the present that O’Hara had once so intently observed.

The stock of reality that O’Hara has uniquely recorded is reactivated, coming to life in a rather strange transmission anchored by the title of each piece. Red Hook’s Kentler Drawing Space has three dozen drawings in its archives, each rendered in caps as LIVE TRANSMISSION: MOVEMENT OF BUTOH DANCER, or LIVE TRANSMISSION: MOVEMENT OF THE HANDS OF PIANIST MARTHA ARGERICH

Her project is a strange and powerful communion with the confines of time and interpersonal entanglements. It seems like an easy project to grasp, yet soon as you think you have it, there’s something you missed.

But at 77, O’Hara isn’t highfalutin about her work. With a shrug and a steely smile, she tells me the practice of Live Transmission gave rise to the term “performative drawing” in French and German newspapers, where more has been written about Live Transmission since the late 80s.

O’Hara wears a black kimono-inspired jacket with a high-collar that reminds me of Daenerys Targaryen, the dragon queen from Game of Thrones, but instead of fire she’s fortified with green smoothies, particularly a super-green smoothie she recommends to me at Le Pain Quotidien near her rent-controlled apartment in the West Village (her old haunts, Caffe Dante and Cafe Ino have been gutted or changed beyond recognition.)

She talks about surviving as a full-time artist, a decision she came to in her late 30s, while many of her friends succumbed to addiction, left the city, or gave up art entirely.

“I’m fortunate. And I say that with 200 dollars in the bank.”

O’Hara’s work has gained more traction in The States since 2016. The New York Times highlighted her project, “Handwriting the Constitution,” where O’Hara started to handwrite the constitution on Jan 21, 2016, the inauguration of 45, in the Rose Room of the New York Public Library.

It was a silent form of protest, one amiable to introverts, where O’Hara (and the dozen others who surprised her by showing up) contemplated the constitution and the freedoms it would uphold.

“There was freedom in that room. Everyone felt reaffirmed that our values would hold.”

It’s not for nothing that her practice has at times been labeled “responsive witnessing.”

A Live Transmission in the making

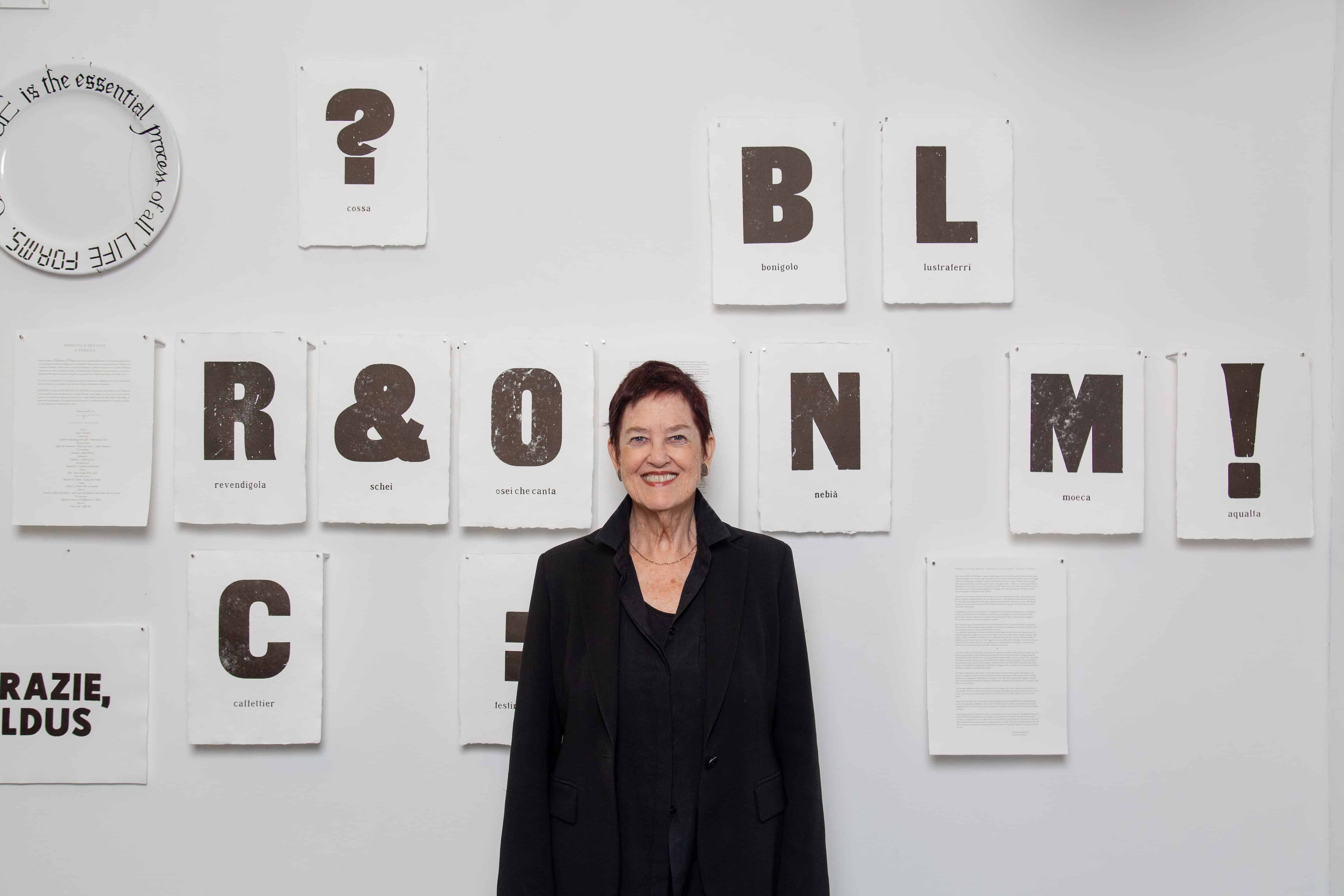

In 2019, O’Hara already has three exhibitions planned. Her first is on display now at Roll & Hill in SoHo and features over forty pieces “Live Transmissions.” In the past, O’Hara has celebrated openings of “Live Transmissions” by working with a musician or dancer or actor to capture their movement with the audience, then adding that piece to the exhibition. But lately, as Roll & Hill staff told me, O’Hara has opted out of public performances.

Several have noted that O’Hara’s lack of reputation in the states could be due to the fact that she’s traveled to so much. Indeed, she’s exhibited at more museums in Europe than in North America. Some speculate that’s because she’s so itinerant. But some of that traveling helped her land work in museums across the world, including The British Museum.

For decades, O’Hara has led a dedicated artist’s life in a city that overwhelmingly demands compromise.

“When I look back at it now, I’m just amazed I’ve survived.”

Granted, her apartment makes it all possible. In 1982, rent was $405 a month for her one-bedroom built in 1850; it froze at $800 then O’Hara took advantage of a senior citizen program called where the city pays landlords the leftover amount.

“The landlord’s happy, I’m happy. It’s a win-win for everyone. I wish more people knew about it.”

Communion

The first Live Transmission was from 1981 in San Francisco. O’Hara was at a Chinese restaurant and watching the chef throw multiple dishes into the area with his wok. The choreography of oils and spices intrigued her, and she found herself drawing the fleeting moment, hoping to get it all on paper in quick, seismographic strokes.

“It was just a one drawing. I never thought they’d be another one.”

One of the most inscrutable and vital aspects of Live Transmission is what O’Hara is connecting. Is it moment to moment? People to people? Both? O’Hara has said that growing up in Japan helped her adopt a less egocentric perspective. In a Bomb Magazine interview, she stated, “It is my intention to eliminate the ‘distance’ between the performance and the subject being observed. The document is the bridge between the two. I am interested in working the fine line between life and art.”

These are drawings that make me think of that great Yeats line from “Among School Children” — “O body swayed to music, O brightening glance/ How can we know the dancer from the dance?” These lines are about communion. Within oneself, across oneself. They push us to expand the contours of humanity.

O’Hara has always been about connecting distinct cultures. Growing up, she learned Japanese, French, and English at the same time. In San Francisco, she taught at the French American International School for the International Baccalaureate program. At 30, she studied the psychology of painting in San Francisco.

“After seven years of doing that, I realized I was more of an artist than I was a therapist. I wanted to go back and do the art world on my own terms, so that’s how I ended up in New York.”

She worked admins jobs until discrimination sunk in.

“Ageism started around 55. I remember the moment clearly where this young manager looked at me and said there’s no way you can do this.”

She’s been winging it through her art ever since. It’s a penury but rich way to live.

“I’m sure with most artists, they’ll tell you that at some point you have to believe that it’s the right thing to do. You get to that point and nothing else matters. It’s all worth the risk.”

Red Hook residents can visit O’Hara’s work through the archives at Kentler Drawing Space.