For my book club, I suggested we read Cormac McCarthy’s newest novel, The Passenger. I’m not, by any stretch of the imagination, what you’d call a McCarthy expert. Over the years I’ve taught The Road to great success in high school creative writing classes, and it remains the first and only McCarthy novel I’ve read. I am, however, very aware of McCarthy’s influence on modern American literature, one of those writers that you should read. I respect him from afar. Despite knowing this, I’ve had a copy of All The Pretty Horses on my bookshelf for years that has remained unopened. Somehow my all women book club (so far we’d only read women authors) seemed like the right opportunity to explore more McCarthy. Retrospectively this was not well thought out on my end.

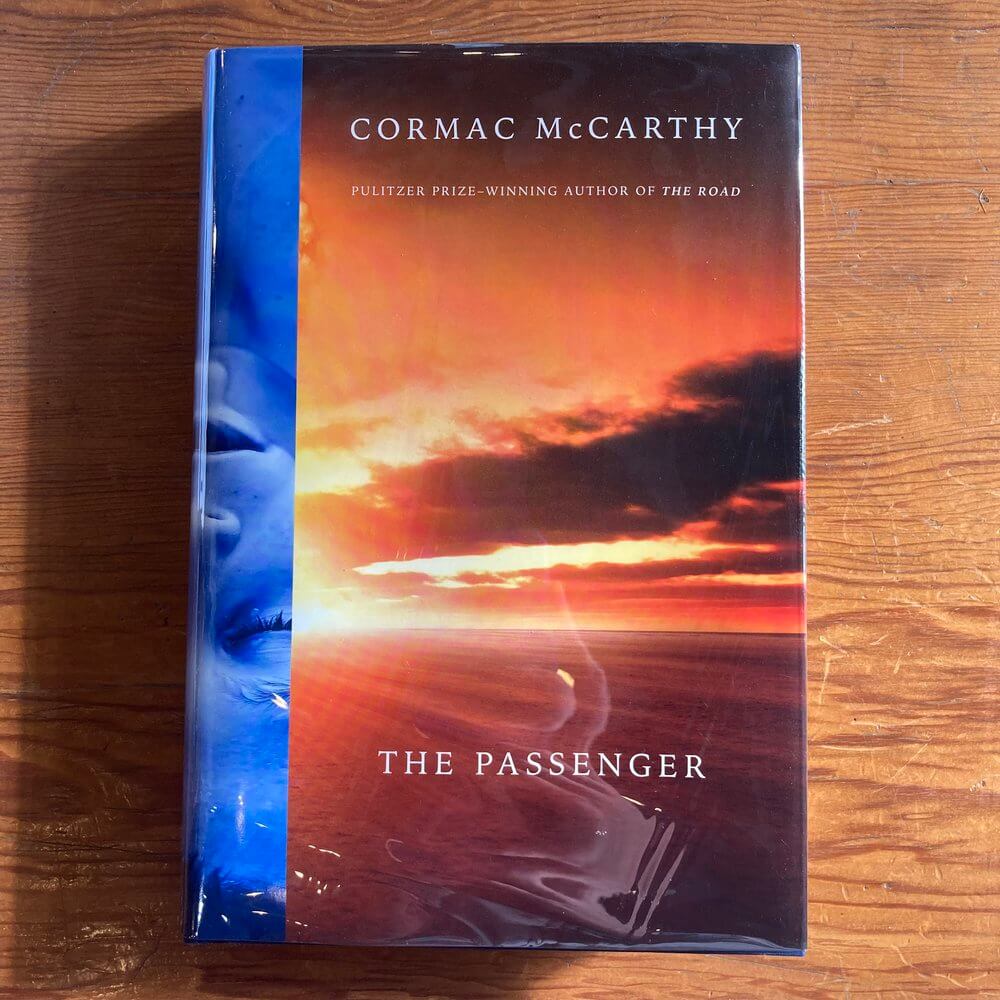

I was primarily intrigued by The Passenger since McCarthy wrote the book at age eighty nine. In a highly ageist society, I wanted to support his efforts. I was also intrigued that the two companion novels, The Passenger and Stella Maris, released within a month of one another in fall of 2022, focused around a brother sister relationship and that McCarthy was writing a central female character for the first time. When most of us think McCarthy, we see taciturn men, the west, blood, guns, death, violence. We think of stereotypical American masculinity. I wanted to know what explorations of femininity such a man, and a man in the later part of life, would conjure up.

The book opens with a young woman taking her life. Soon after, we are introduced to a series of conversations between Alicia, the young woman who has died, and the character she converses with during her ongoing and acute struggles with paranoid schizophrenia known as “The Kid.” The writing is abstract, cerebral, sparse. The first few pages don’t include a plot to speak of. McCarthy uses italics to mark Alicia’s mental projections and that’s about the only help we get. To her, these conversations are real, so they are real for readers, too. They can be maddeningly intellectual yet maddeningly meandering. It is possible to think McCarthy is intent on scaring off readers. I personally like to think at age eighty nine, you write exactly what you want. Throughout the book, McCarthy continues to include Alicia’s internal monologues without advancing or reversing the plot. Plus, we know she’s dead.

The central conflict in the novel is the forbidden love between brother and sister, but McCarthy treats their relationship from a sanitary, yet internally tortured vantage point. There is pain and sorrow, but there isn’t much action. The siblings have buried everything deep down and this repression is mirrored in the pacing of the novel itself. Alicia and her brother Bobby, who is referred to mostly by his last name, “Western” live in prisons of their own brilliance and stuntedness, two sad stars who never find their place in society. Throughout the novel, there is also the thread of a missing passenger recovered from the wreckage of a plane, but most of the novel follows Bobby from bar to bar in New Orleans, his only living companion, a cat. Bobby is so solitary that even that cat disappears.

My book club members didn’t make it beyond the first few pages. Truthfully, I can see why. I kept reading out of a mix of curiosity and stubbornness—I’m an English teacher, after all. I wouldn’t give up. The Passenger is, in many ways, impenetrable. It asks readers to embody reading as opposed to hanging on to details, characters or places. McCarthy has set us afloat in his exploration of life’s most potent topics: grief, loss, longing, desire—all that is forbidden and unattainable.

Despite the abstraction of the novel as a whole, I found myself tearing up in the last few pages of the book as Bobby lives out his aimless days in Spain. The Passenger is a meditation on loneliness. It’s a study of loss, of wanting things that you can never have back. The Passenger speaks to the sincerest depths of grief. McCarthy doesn’t tie himself down with creating a world where there is hope. Bobby’s world is hopeless and he knows this. The question is what will he do? In the second half of the novel, Bobby spends a winter alone in a deserted cabin. He sleeps among the rodents. He has no one, nothing. He is kept alive by thoughts and memories of his sister.

So why do we read hopeless books about hopeless lives? To inhabit the recesses of other people’s psychology – to understand their experiences. At eighty nine, with twelve novels behind him, there is no question that McCarthy knows exactly what he’s doing. He’s created a novel that stretches a mood of despair across all 383 pages. If you’re interested in carefully examining the exquisite pain-fullness of surviving despite yourself, McCarthy offers you this meditation. If you don’t like it, he doesn’t care.

I have Stella Maris in my library queue, but I’m waiting for the right time to dive back in. The time I suggested we read The Passenger and everyone hated it has become the stuff of book club mythology.