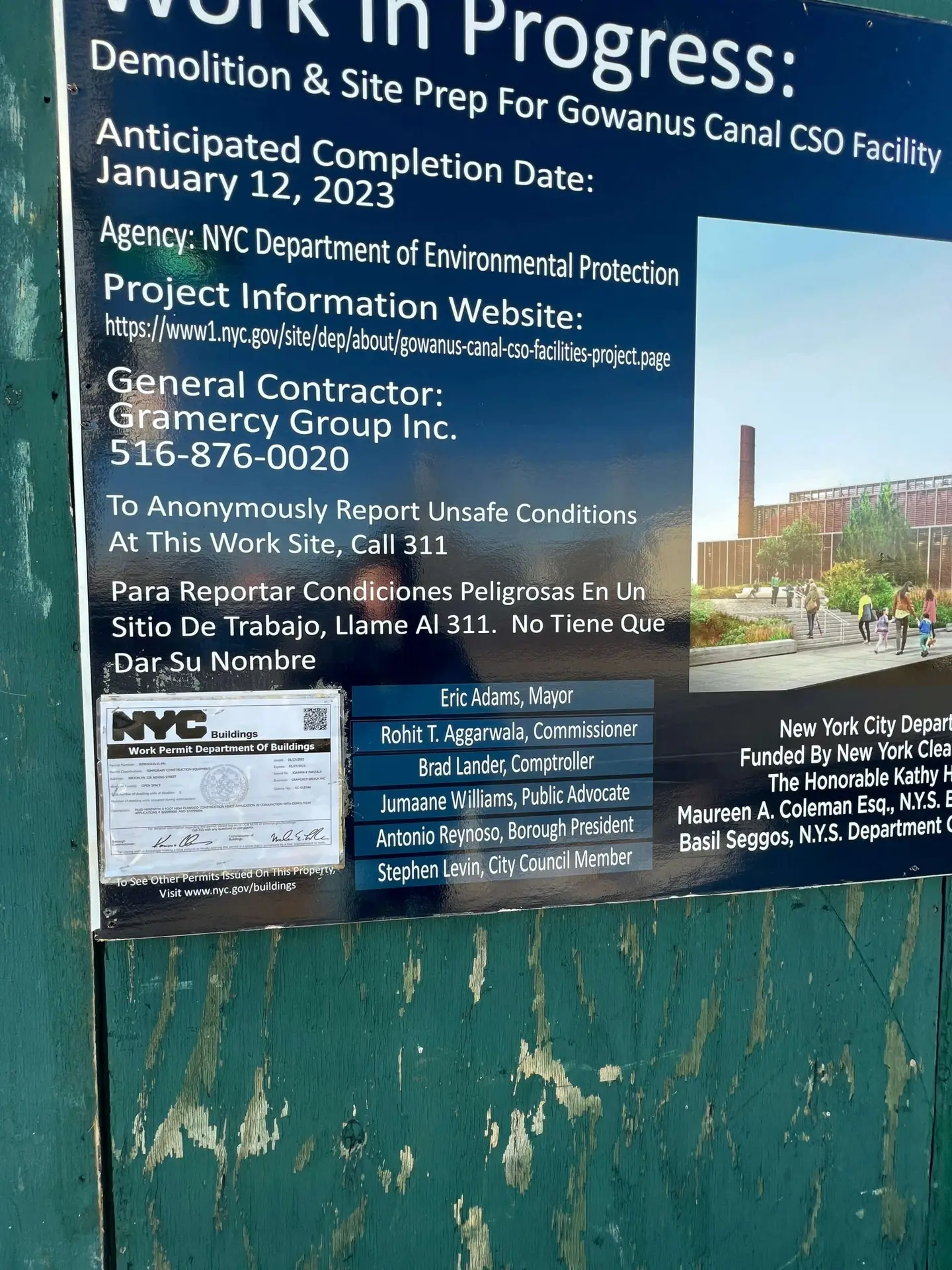

In December, The New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), overseen by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), began the second phase of construction of Gowanus’s two Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) tanks after pausing work since August.

Because of the design of the much of New York’s sewer system, where stormwater and sewage water both go through the same pipe, it can easily be overburdened by rainwater; if that happens, the water is diverted from the pipe leading to the water treatment plant, to the nearest body of water. In Gowanus, this means that about 40 million gallons of untreated sewage water enters the Gowanus Canal every year.

The CSO tanks are part of the Superfund cleanup of the canal, and once finished in the first half of the 2030s, will capture the sewage water and store it there until it can be pumped back into the sewer system and the treatment plant.

But construction of the “Red Hook” tank, located at the top of the east side of the canal between Butler Street and Sackett Street, has been mired by community complaints. As we highlighted in our September issue, ever since the first phase of work started in the fall of 2023, residents of the area have experienced noxious odors coming from the construction site, with varying — and often lacking — levels of responsibility taken by the involved agencies.

Phase 1 involved driving concrete panels down to bedrock along the perimeter of the site to support removing the soil that will give room to the future sewage holding tank. To build the wall, workers had to excavate soil 200 feet down; the dug-up soil, which was contaminated with coal tar and other chemicals, emitted odors that on some days was strong and potent enough to reach far beyond the tank site, according to neighbor testimonies.

Many community members were, therefore, concerned that the second phase of construction — excavating the soil within the perimeter wall — would result in more headache (literally — some residents reportedly got headaches from smelling the site). Both DEP and EPA have maintained that this part of construction will not lead to as much odors, as excavation will be conducted at a much shallower depth, where the soil is not as contaminated.

DEP presented four options to EPA for phase 2 of construction. Three of them involved a tent — either a tent covering the entire site or a tent covering half of it which could be moved — while the fourth one meant accelerating the work and shorten it by about half, from ten months to five.

During multiple Gowanus Community Advisory Group (CAG) meetings during the fall, members of the CAG asked DEP and EPA that the community would get a say in which of the four options the agencies would move forward with. In the end, EPA directed DEP to proceed with the fourth option — the accelerated timeline — with no community input, but the federal agency instead called a public meeting to explain the next steps, answer questions and clarify what steps would be taken to make sure odors are monitored and acted on more stringently.

During multiple Gowanus Community Advisory Group (CAG) meetings during the fall, members of the CAG asked DEP and EPA that the community would get a say in which of the four options the agencies would move forward with. In the end, EPA directed DEP to proceed with the fourth option — the accelerated timeline — with no community input, but the federal agency instead called a public meeting to explain the next steps, answer questions and clarify what steps would be taken to make sure odors are monitored and acted on more stringently.

On Dec. 10, representatives from EPA and DEP presented to the community a detailed plan for phase 2 of construction. Tom Mongelli, remedial project manager at EPA, began by giving an overview of the Gowanus Canal cleanup and the CSO tank project, as well as what air monitoring had been conducted during the first phase. He was followed by Dr. Lora Smith, human health risk assessor at EPA, who went into further detail on the results of the past year’s air monitoring.

“In order to move forward with an accelerated plan, we knew we’d have to put every health protection and mitigation measure available into place. So, not only do we need to protect public health, but also manage the odors, which might not be detected at a level of health concern, but have very much impacted the community,” she said. “We are sensitive to these concerns and they have been taken into consideration in the updated approach.”

According to the data collected around the tank site, levels of naphthalene, a carcinogen chemical that smells like mothballs, were below a health-based level of concern. Naphthalene can have a strong odor, meaning that even at levels far below what would constitute a health hazard, it can still be smelt in the air, Dr. Smith noted.

During the next phase of work, Mongelli then shared, there will be increased air monitoring and enhanced mitigation measures, to minimize the impact of the work on neighbors’ quality of life. “ If the measures prove to be ineffective, EPA is prepared to stop work and direct DEP to construct a tent over the excavation before work can proceed,” Mongelli added.

Examples of the additional monitoring tools the agencies will use, Dr. Smith said, is a Trace Atmospheric Gas Analyzer (TAGA) bus and naphthalene dosimeter sensors. The TAGA bus — of which there are only two in the entire United States — can measure naphthalene at the parts-per-billion level, as can the dosimeters.

EPA has also increased its air monitoring requirements. It’s maximum acceptable limit of naphthalene for the entire project — three parts per billion — is set based on chronic toxicity value, meaning that if someone were to be exposed naphthalene at the level EPA has set for their entire life, that person wouldn’t see any deleterious effects, according to Dr. Smith. (Of course, the CSO tank construction will likely not go on for more than an decade.) If data on total volatile organic compounds collected through the Comprehensive Air Monitoring Program exceed one part per million, work at the site will also be paused. Overall, the federal agency has been conservative when setting its limits on naphthalene and other potentially harmful chemicals.

During the questions-and-answers portion of the meeting, it appeared that some community members remained weary and skeptical that DEP and EPA would deliver on their promises of increased air monitoring and mitigation. But there was also cautious optimism, with multiple people voicing their appreciation for EPA and DEP’s efforts to find a solution that takes into account the concerns of the community.

It does remain unclear what will cause EPA to halt work at the site. Mongelli couldn’t give a threshold for number of complaints or what criteria the agency would use to make the determination, but he said that he hoped that the data, which will be reviewed daily, would show trends that EPA and DEP could quickly act upon if needed. Dr. Smith clarified that EPA will look at both the quantity and magnitude of the concentration of naphthalene, as well as the quantity and magnitude of the odor complaints, when determining whether to halt the work.

Phase 2 is scheduled to be complete by summer 2025.

Author

-

I’m a New York-based journalist from Sweden. I write about the environment, how climate change impacts us humans, and how we are responding.

View all posts

I’m a New York-based journalist from Sweden. I write about the environment, how climate change impacts us humans, and how we are responding.

Discover more from Red Hook Star-Revue

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.