In 2005, the HarperCollins imprint William Morrow published the memoir No Lights, No Sirens: The Corruption and Redemption of an Inner City Cop by Robert Cea, a former New York City Police Department (NYPD) officer. The book chronicled Cea’s days in uniform in the stygian “Badlands” patrolled by the 76th Precinct in the 1980s and ‘90s.

According to Cea, “the 7-6 was a dumping ground of sorts. That meant, in simple terms, that if a cop fucked up on the job, but was lucky enough to beat a judicial trial and subsequently a departmental trial, the job would punish him, or her, with a transfer into these ‘dumping ground’ precincts, hopefully never to be heard from again.

“Most of the time these places were in far-off environs where you would not have the chance to deal with real people or real cops ever again. Whether they were in industrial areas, or hellhole armpits of the city, they guaranteed one thing: You’d never have to be bothered with normalcy again. Welcome to Red Hook and Gowanus.”

Cea’s determination that the New York City residents whom he’d sworn to protect and serve were not “real people” was reflected both in his language choices – to him, everyone in Red Hook was an “animal,” the epithet he used again and again, alongside occasional racial slurs – and in his consistently cruel and illegal behavior. With the approval of his colleagues, he brutalized suspects as a preemptive form of self-protection (“Neutralize first: ask questions later”) and ransacked homes without a warrant.

He robbed drug dealers for heroin, which he used to bribe informants. He wrote up arbitrary charges of disorderly conduct to throw people in jail when he didn’t like the looks of them: “You don’t have any ID and are standing in a drug-prone location, or just look suspicious – BANG, you’re sleeping in some smelly precinct for three days.”

He elicited false confessions: “[I’d] lie to the perps, allowing them to think that confessing on camera would lead to an extremely light sentence, probably time served would be all.”

Frequently, he offered dishonest testimony in court to protect himself and his fellow officers, describing an “arrest exactly the way it wasn’t… the way the judges wanted to hear it so their calendars were cleared when the mopes pled out, and the way I wanted to tell it to keep the animals in the cages where they belonged.” The officers called it “test-i-lying.”

Cea rationalized this crime-stopping approach by depicting Red Hook as a place so deadly that he had to operate outside the rules to survive. “You see, in order to thrive and excel in working environments like the Badlands, you have to become the monster that surrounds you,” he wrote.

No Lights, No Sirens was not an apology. The victims of Cea’s story were not the people of Red Hook; the victim was Cea himself, whose noble and unremitting commitment to crime prevention put him in such intimate proximity to humanity’s ugliest creatures as to compromise his inner peace. He cared too much, couldn’t get the job off his mind, and lost his marriage as a result. He had to retire to save his soul – whereas no one in Red Hook had a soul to begin with, apparently.

No Lights, No Sirens was not an apology. The victims of Cea’s story were not the people of Red Hook; the victim was Cea himself, whose noble and unremitting commitment to crime prevention put him in such intimate proximity to humanity’s ugliest creatures as to compromise his inner peace. He cared too much, couldn’t get the job off his mind, and lost his marriage as a result. He had to retire to save his soul – whereas no one in Red Hook had a soul to begin with, apparently.

But Cea’s writing made clear that his concern had never been public safety. In his account, the cops functioned as a street gang almost indistinguishable from rival outfits, seizing power for its own sake. Cea and his partner liked to cruise Columbia Street, laughing as civilians fled in fear at the sight of them. “I felt like this was my kingdom,” he bragged.

Commuting from a waterfront McMansion on Long Island, Cea became addicted to the thrill of the street life in Red Hook, whether that meant participating in a gunfight in the projects (“I actually felt more alive than I had ever felt before”) or watching without intervention as a drug dealer forced a woman to perform oral sex on a stray dog (“I must say that I was curious”).

Cea, however, thus summarized his work: “The laws I broke were without question only directed at men who would not think twice about killing any one of us, regardless of sex, age, color, or creed, and the sad thing about all of it is, without men like me who would dare to question these laws, which are built solely to protect only the bad guy, the streets would be owned by the animals I tried so hard to arrest. Democracy in a place like New York City doesn’t work, the reason being, it’s too diverse. Ask Rudy Giuliani, who reigned as an absolute monarch, and dragged the city kicking and screaming into lawful prosperity. His ‘monarchy’ allowed every cop in the city to get right the fuck up in the face of the animals who ran the city under the administration of the fabulously inept David Dinkins.”

Broken Windows and stop-and-frisk

Starting in 1994, Mayor Giuliani brought a new theory of policing called “Broken Windows” to the NYPD, which sought to crack down forcefully on minor signs of social disorder in the city, from graffiti to loitering to public urination, under the premise that small illegalities created a hospitable environment for more serious unlawfulness. Crime went down – mirroring, however, a nationwide decline that included other American cities that hadn’t instituted more aggressive policing.

Starting in 1994, Mayor Giuliani brought a new theory of policing called “Broken Windows” to the NYPD, which sought to crack down forcefully on minor signs of social disorder in the city, from graffiti to loitering to public urination, under the premise that small illegalities created a hospitable environment for more serious unlawfulness. Crime went down – mirroring, however, a nationwide decline that included other American cities that hadn’t instituted more aggressive policing.

The local and national media, however, widely interpreted correlation as causation in New York, and Giuliani’s successor, Michael Bloomberg, doubled down on Giuliani’s empowerment of the NYPD in 2002 by promoting “stop-and-frisk,” a policy that encouraged officers to temporarily detain and search people on the street without probable cause to arrest. The policy led to 97,296 stops in Bloomberg’s first year. By 2011, the annual number had climbed to 685,724. About 90 percent of the New Yorkers stopped were black or Latino.

Under Bloomberg, the NYPD also orchestrated a large-scale raid of the Red Hook Houses in 2006. Prosecutors indicted 143 of the arrestees “in connection with what they said was a $250 million conspiracy to sell drugs in Red Hook. The indictments charge that drug dealers divided up the neighborhood and set the cost of drugs and sale locations,” the New York Times reported.

The raid in Red Hook represented the culmination of an ambitious series of surprise attacks upon New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) developments, which aimed to crack down on drug operations by rounding up dealers en masse and slapping them with felony conspiracy charges that could lead to life sentences. Some Red Hook Houses residents praised the police’s zeal; others felt that the NYPD seemed to be responding to intel from the ‘90s, going after gangs that in reality had already mostly disintegrated.

In any case, as the Times wrote two years later, “the strategy stumbled at the courthouse steps. Judges rebuked the prosecution tactics. Juries rejected the conspiracy charges. And after six years, eight major operations and more than 500 arrests, no one has been convicted of first-degree conspiracy. Instead, many defendants have spent a year or more on Rikers Island, awaiting trials that in the end never come. Typically, they plead guilty to lesser crimes, are sentenced to time served and then are released.”

In 2013, Bill de Blasio won the mayoralty on a promise to “end a stop-and-frisk era that targets minorities.” While he didn’t ban the procedure outright, he managed to reduce the number of annual stops to 11,629 by 2017. Though de Blasio disappointed progressives by reappointing Giuliani-era Police Commissioner William Bratton, he earned credit for NYPD reforms such as implicit bias training and body cameras.

De Blasio also implemented “neighborhood policing,” a “program to build stronger partnerships between police and the communities they serve.” Neighborhood Coordination Officers (NCOs) appeared in 2015, embedding themselves as friendly presences in the Red Hook Houses and elsewhere to serve as liaisons between the police force and a sometimes mistrustful citizenry.

“That’s what neighborhood policing is all about: seeing the same officers every day in your community,” Captain Tania Kinsella, the commanding officer of Police Service Area 1 (PSA 1), said at a tenants association meeting in January. PSA 1 patrols public housing in Red Hook in collaboration with the 76th Precinct, which handles the rest of the neighborhood. Kinsella explained that, if an officer is deeply familiar with the locals, he or she is more likely to be aware when someone in the neighborhood suffers from a mental illness, for example, and needs to be sent to a hospital instead of being taken to jail when causing a disturbance.

At de Blasio’s 2019 State of the City address, the mayor boasted, “The NYPD has pushed crime to record lows, with the fewest homicides since 1951. Neighborhood policing is now the reality in this city, and it works.” De Blasio attacked the “conventional wisdom” that “you can only arrest your way to a safer city,” noting that in 2018 “the NYPD made 140,000 fewer arrests than the year we took office.”

In Red Hook, according to longtime community leader Robert Berrios, “relationships between police and the community have been great, and the reason for this is NCO officers,” whose Build the Block meetings have seen “more and more” attendees. Berrios observed that most residents recognize that the police “are not the bad guys,” and he opined that “those who complain about the police in the community are the same ones who cause havoc within the community.”

He added, “What some people don’t understand is [that] police go where the community asks them to be. Some parts of Red Hook have issues with drugs, others with loud music. [The police] even respond to residents when they have no lights or heat.”

RHI study

In January, the Red Hook Initiative (RHI), a youth empowerment and social services nonprofit, quietly released a “participatory action research project,” compiled principally by its adolescent clientele. It offered a starkly different view of the activities of the 76th Precinct and PSA 1.

Titled Real Rites Research: Young Adults’ Experiences of Violence and Dreams of Community-Led Solutions in Red Hook, Brooklyn, the RHI study asked for a measure of local sovereignty in the effort to create a safer neighborhood: “Our research suggests that effective approaches to violence prevention lie with young people and from within the community itself. To reduce experiences of violence in Red Hook we need community programs and support for young people as leaders, mentors, and experts.”

It continued: “We must separate police from community building. Young people report policing as a major cause of violence in Red Hook. Police harassment inhibits young people’s ability to interact with others and to feel free within their own community.”

For the older crowd at the Red Hook Houses’ tenants associations, which regularly welcome NCOs at their monthly meetings, the police appear to represent safety. For the teenagers at RHI, who reported that the local police presence makes them “feel like targets and animals,” the opposite seems to be true.

Alex S. Vitale, a sociology professor at Brooklyn College who writes about the problems of policing in America, admitted that some of the police encounters interpreted as harassment by young people in communities of color stem from calls for assistance within the same community, not from an external mandate.

“Part of the problem here is that those folks who are calling the police also wish that there were better community resources, that the schools were better, that the quality of the housing was better, but what they’ve been told for the last 40 years is that the only thing they can have to solve their community problems is more police,” he explained.

“The police also are kind of actively promoting themselves as the saviors of the community,” he went on. “And the elected officials largely go along with this, instead of saying, ‘Why can’t we have adequate afterschool programming? Why can’t we have trauma counseling for these young people? Why can’t we have family supports in place? Why isn’t there a well-funded football league with lots of coaches and assistant coaches who are paid and can do mentoring?’”

According to Vitale’s 2017 book The End of Policing (Verso Books), “the police exist primarily as a system for managing and even producing inequality by suppressing social movements and tightly managing the behaviors of poor and nonwhite people: those on the losing end of economic and political arrangements.” In the 19th century, the “three basic social arrangements of inequality” were “slavery, colonialism, and the control of a new industrial working class.” When these arrangements yielded “social upheavals that could no longer be managed by existing private, communal, and informal processes,” modern policing was invented.

Bob Gangi, a Manhattan-based activist at the Police Reform Organizing Project (PROP), shares many of Vitale’s views. “I think that the city could and should do a much better job of collaborating with communities to improve services and programs in the communities. I don’t think the city should do that through its police department,” he said.

[pullquote]“Right now, the police is responsible for safety in the public schools; that should be the responsibility of the Department of Education. Right now, the police is responsible for regulating street vendors; that should be the Department of Health or the Department of Consumer Affairs.”[/pullquote]

In Gangi’s view, the police are tasked to solve social problems – mental illness, drug addiction, homelessness, and more – that don’t actually benefit from the use of armed enforcers. “Right now, the police is responsible for safety in the public schools; that should be the responsibility of the Department of Education. Right now, the police is responsible for regulating street vendors; that should be the Department of Health or the Department of Consumer Affairs.”

PROP advocates for “significant reductions in police power, police budget, and police personnel,” which “could literally save billions of dollars” for schools, mental health services, drug treatment programs, and public works projects.

Gangi also accused NYPD precincts of using a quota system that forces officers to make arrests without justification. “It’s not a policy that’s written down anywhere, because it’s illegal, but anybody who knows how the NYPD functions knows that a lot of it is driven by numbers. The cops know that, and if they want to advance up the ranks and they want to avoid being sanctioned or losing their vacation or being assigned to a more difficult post, they’ll make their numbers.”

PROP volunteers monitor New York City’s courtrooms to record which crimes are being prosecuted and who’s being prosecuted for them. The latest report noted that, in the summer and fall of 2018, 87 percent of criminal trials and 90 percent of arraignments involved New Yorkers of color. “The NYPD, in one form or fashion, targets every vulnerable population in the city,” Gangi asserted.

He acknowledged that the NYPD is not unique in this way: “There is no police department in any big city that provides a useful model.” In other words, there’s a fair chance the NYPD isn’t the worst out there.

16 percent approval rating

Amanda Berman, project director at the Red Hook Community Justice Center, pointed out, however, that the problems of other cities’ police departments can have just as big an effect on New Yorkers’ perceptions of the NYPD as the NYPD’s own behavior. In 2016, Berman observed that, with public safety on the rise and arrests on the decline in New York, people in Red Hook were beginning to like the NYPD less, not more.

A collaboration between the New York State Unified Court System and a private nonprofit, the Justice Center seeks to foster legitimacy and trust in the justice system, from law enforcement to the courts. Every few years, the organization surveys Red Hook residents to gauge its progress.

The first survey took place in 1997, before the Justice Center opened, and at that time, only 14 percent of people in Red Hook generally approved of the NYPD. By 2001, the number had jumped to 42 percent. In 2009, it climbed to 66 percent. The most recent survey went out in the summer of 2016.

“That was the summer where, for several months, it felt like every time we turned on the news there was a new story about conflict between police and a community. That was the year of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile and when the officers were killed in Dallas,” Berman recounted. “There was a palpable tension building here in Red Hook. We were hearing from community members as well as the police.”

The former were “angry and scared and concerned” about police violence in the national media, while the latter reported that they “felt unsafe” in the resulting climate of animosity. In 2016, according to the Justice Center, the NYPD’s approval rating in Red Hook was 16 percent.

Berman believed that the Justice Center could play a role in healing the rift between the community and the police. Their Peacemaking program, a dialogue-based method of conflict resolution inspired by Native American traditions, reached out to the local NCOs and trained them as Peacemakers, allowing them to mediate disputes between civilians through communication instead of enforcement. 15 officers have taken the course thus far.

The Justice Center also created Bridging the Gap, a program designed to introduce young people to officers in the neighborhood in order to spark discussions within a setting of “equal voices” and to dispel stereotypes on both sides. Sometimes the kids bring their parents, too.

“Youth are encouraged to ask questions, even the tough questions, and the officers commit to answering them honestly. And what we found is that it’s really empowering for the young people to be asking their questions but also to be asked questions – for them to know that the officers care about what they think and how they see the world,” Berman described.

At a Bridging the Gap game night at the Miccio Center last fall, hula hoops and Pictionary gave way to discussion circles. Some kids sat silently, while others peppered the officers with questions about how they decided to become cops and what kinds of dangers they face in the line of duty. Several expressed admiration, with one high-schooler comparing their bravery to that of U.S. troops serving overseas.

One adult woman asked the officer sitting next to her what he thought of stop-and-frisk. He answered briefly, calling it a good policy and a useful procedure.

Later, a teenager mentioned that some of the videos he’d seen of police on the internet or on the news had troubled him and questioned whether cops sometimes went too far when using force. In reply, an officer told the kids that they shouldn’t trust the media, since most of it is lies.

Berman plans to organize another survey this summer. She hopes to see an improvement in the police’s approval rating.

Keith Owens, an AmeriCorps member who works at the Justice Center and lives on Dwight Street, encapsulated the central complaint behind 2016’s disconcerting statistic: “Stop shooting to kill! Shoot to wound. If somebody’s not taking a shot at you, but you still feel the need to use force, just wound them! Shoot them in the leg.”

Owens himself has had mixed experiences with the NYPD. “Some [encounters] have been fair. Others haven’t been.”

One experience from 2017 sticks out: “One of my girlfriend’s sons got arrested for smoking weed inside the NYCHA buildings. But at the time we found out, we didn’t know. All she knew was that her son got locked up. So we came out here running, trying to figure out where and who. I jumped in front of the cop car, just to stop them so that the mother can find out information.”

The officers misinterpreted Owens’s interference, and before long, they had him pressed against the car, with backup on the way. “Now I’m being held down on the car by six police, and then one officer snuffed me. He hit me – he walked right up to me and snuffed me right in my mouth. There was literally nothing that I could do about it because I was already being held by police.”

The shooting of Tyjuan Hill

Owens’s nonlethal experience may bear a small resemblance to another, more tragic incident that took place in Red Hook five years earlier.

On September 20, 2012, after a short chase following an attempted arrest, five officers from the 76th Precinct had pinned 22-year-old Tyjuan Hill to the blacktop at the corner of Hamilton Avenue and West 9th Street when a sixth, Sergeant Patrick Quigley, pressed a gun to the back of his head and fired. Hill died instantly.

For the NYPD, the night began at the intersection of Henry and Huntington streets, behind a gas station, where a female undercover officer, Cairly Rivera, posed as a sex worker and waited for johns to solicit her. At least nine other officers sat in waiting. The sting took place under the auspices of Operation Losing Proposition, which has generated arrests and automobile seizures for the NYPD since 1991.

By 10 p.m., the officers had already taken into custody one man, who sat under police supervision in a nearby van as the operation continued. At that time, a Mazda sedan with four young men inside pulled up to Rivera, and they negotiated for her services. With a deal in place, the police moved in. All four men exited the vehicle, and the police promptly arrested three.

The fourth, Hill, ran. After a conviction for second-degree attempted robbery and 18 months at Washington Correctional Facility, Hill had come home to the Red Hook Houses that February. While his friends would at worst face misdemeanor charges for patronizing a prostitute, the bust would mean a parole violation for Hill.

Six officers gave chase, either by car or on foot. Bradley Tirol tackled Hill opposite 288 Hamilton Avenue. Lyheem Oliver came next. Daniel Casella, Benigno Gonzalez, and Sambath Ouk then joined as the officers sought to subdue Hill by grabbing his arms and legs and pressing down on his back. According to the police, Hill resisted arrest, and Casella began to strike him with an ASP (an expandable baton or nightstick). Quigley was the last to arrive on the scene.

Collectively, the officers weighed about 1,200 pounds. Hill stood five foot-ten and weighed 171 pounds. Still, by their story, they couldn’t fully secure his arms and managed to cuff only one of his hands. Face down in the street, with the police still on top of him, Hill allegedly managed to pull a concealed pistol from his waistband and point it at Quigley, who was kneeling with a hand on Hill’s back. Quigley then drew his own pistol and fired at Hill in avowed self-defense.

[pullquote]“[Hill’s] firearm was pointed at my face. And I made the decision to shoot him in his head.”[/pullquote]

In Quigley’s testimony, “[Hill’s] firearm was pointed at my face. And I made the decision to shoot him in his head because that was the only available target open to me, but more importantly, I knew that by doing that, it was – it would stop him from shooting me. It would definitely end that situation. That’s why I did it.”

The Brooklyn District Attorney’s Office declined to pursue charges against Quigley, but two months after Hill’s death, Hill’s mother, as administrator of his estate, filed a civil rights lawsuit against the City of New York and the officers involved in the shooting. Judge Alvin K. Hellerstein dismissed the complaint against the city, but in October 2016, six officers went to trial before a jury in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York.

If found guilty of excessive force or failure to intervene, the policemen (or their employer) would have to compensate Hill’s estate for the value of his lost life with a sum determined by the jury. Civil trials employ a less rigorous standard for guilt than criminal trials, which demand proof beyond a “reasonable doubt.” Civil court asks for a “preponderance of the evidence” on the side of the plaintiff.

The plaintiff’s case looked strong. Even at first glance, the NYPD’s story had elicited some public suspicion, since the location of Hill’s bullet wound seemed to suggest that, while fighting off five officers, he would have had to have pointed his gun backward, over his shoulder, to endanger Quigley.

Moreover, Hill’s attorneys – Michael Colihan, Phillip J. Smallman, and David B. Shanies – had lined up four eyewitnesses with no personal connection to the deceased or to the NYPD. From inside stopped cars, they had seen the event transpire from a distance of 15 or 20 feet, and all four would testify that Hill had had no gun – or, as the court required them to put it, that they’d observed no gun on his person.

One was a woman from Austin, Texas, who had come to New York to scout a job offer. Her best friend had accompanied her to New York to celebrate her birthday. When they saw the shooting, a taxi driver was taking them from Manhattan to Staten Island, where they were staying for the week with another friend.

The cab driver – whom one of the officers allegedly approached in the moments following the shooting, shouting at him through his opened window to “Get the fuck out of here!”– also testified. The fourth witness was a former officer of the Newark Police Department, who had watched from an SUV.

Four years after the shooting, the testimonies varied, especially in the length of time attributed to the incident. The three people inside the taxi recalled that, leading up to the shooting, Hill had had his hands behind his back while the officers beat him. One of the women from Austin called it a brutal five-minute assault, “the worst thing I’d ever seen.” The man in the SUV, meanwhile, claimed that, from the tackle to the gunshot, only five or six seconds had passed, during which Hill had resisted arrest. In his memory, Hill’s hands were on the blacktop, and he was pushing himself upward from a prone position when Quigley fired.

All four, however, were equally confident that Hill had never had a gun in his hand. Hill’s alleged firearm bore a somewhat mysterious quality even in the police’s testimony.

For instance, Quigley remembered that Hill had held it with two hands while pointing it at him. Others recalled that he’d held it with one. Ouk, who had been wrestling Hill’s lower body at the time of the shot, didn’t recall seeing him with a gun at all.

That night, crime scene detective Christopher Florio photographed a Kel-Tec 9-millimeter Luger on the sidewalk on Hamilton Avenue. But no one could explain exactly how it had jumped out of Hill’s hand and over the five-inch curb from the street. Some officers speculated that it may have been kicked at some point. Also curious was the absence of any blood on the gun, given the splatter on Quigley’s uniform and in the surrounding area.

DNA on the gun belonged to Hill, but the police seemed unable to account for the gun’s chain of custody prior to the DNA swab. Florio reported that he’d received the gun from Alejandro Manzano, the officer safeguarding the evidence, at 11:10 p.m. But Manzano’s deposition revealed that, until 12:30 a.m., he’d been stationed at the Mazda left behind at Henry and Huntington streets. Subsequently, he followed orders to watch Hill’s body until the arrival of the medical examiner at 1 a.m. Manzano didn’t recall seeing a gun at the scene at any point.

The defense cited a radio transmission from Officer Tirol, who’d purportedly yelled “Gun, gun, gun!” upon spotting Hill’s pistol. The transmission was preserved and played for the jury.

In fact, there was no reason for Tirol to disentangle himself from Hill in the midst of an urgent situation to use his police radio. What Tirol claimed was that his transmitter happened to turn on at exactly the right moment to catch the exclamation (something or someone must have pressed the button unintentionally) and to turn off before the sound of Quigley’s gunshot. The plaintiff found this story unlikely, speculating that Tirol had staged his recorded panic moments after Quigley’s unprovoked shot.

In spite of all this, Judge Hellerstein prohibited the plaintiff from arguing explicitly that the police had planted Hill’s gun on the scene. The lawyers would have to limit their argument to “what witnesses saw and didn’t see,” and no one had seen the officers drop a pistol on the curb.

Hellerstein also prevented the two witnesses from Austin from speaking about the series of threatening phone calls they’d allegedly received from the police and then from a private investigator hired by the NYPD in the lead-up to the trial, on the basis that the plaintiff had no evidence linking the calls specifically to the six defendants. As the judge put it, “there are individuals on trial, not the police department and not the city.”

Hill’s lawyers wanted to play a 911 call from the time of the incident, placed by the man from Newark, who, even while in a state of alarm, had noted specifically that the victim of the shooting he’d just watched had not had a weapon. Hellerstein, however, ruled that the call was redundant unless the defense impugned the witness’s credibility on the stand.

The defense hired a forensic pathologist to explain that Hill’s autopsy contradicted the story of police brutality (with kicking and stomping) told by the witnesses in the taxi. The expert pointed to the absence of deep bruises or fractures: apart from a couple scrapes and a contusion on his right wrist, Hill’s body bore “no injuries” from the neck down. Arguably, the testimony even contradicted the account of the officers, who had acknowledged beating Hill with an ASP before his death.

After eight days in court, the jury reached a deadlock, resulting in a mistrial. In 2017, Hellerstein dismissed Hill’s claims against Casella, Gonzalez, Oliver, Ouk, and Tirol, but the claim against Quigley remained, and a retrial followed in March 2018.

Second trial and appeal

On the second try, the plaintiff hoped to introduce an “audio and voice identification expert,” who, by enhancing the sound on an iPhone video recorded by a witness just after the gunshot, would seek to prove by a statistical comparison of energy and pitch to the police’s radio transmission that Tirol’s exclamation of “Gun, gun, gun!” could be heard on the witness’s tape as a post-shooting coverup. Hellerstein didn’t allow the testimony: “Several aspects of Ms. Owen’s methodology were unreliable.”

Ultimately, the content of the second trial was similar to that of the first. This time, however, the jury returned a not guilty verdict.

After an unsuccessful posttrial motion, Shanies appealed the verdict on Ms. Hill’s behalf in early 2019. Shanies took issue with the judge’s “permissive” language regarding the use of deadly force in his instructions to the jury: Hellerstein had stated, “If a policeman has probable cause to believe that the person being arrested poses a significant threat of death or serious bodily injury to that policeman or to another, the policeman may use lethal force and even kill the person he is trying to arrest.”

The appellant brief points out that, as established by the District Court, the jury instructions must employ restrictive language: the use of deadly force was “unreasonable unless the officer had probable cause to believe that the suspect posed a significant threat of death or serious physical injury to the officer or to others.”

Shanies also claimed that the jury had received the wrong information on the level of intent that a plaintiff needs to prove in a deadly force case, and he protested the exclusion of 911 calls at the trial.

According to Shanies, the appeal process “will take some months to play out. First the city will file its opposition; we’ll file some additional briefing, and then we expect to have argument before the court. Based on experience, I would expect that probably sometime in the summer or perhaps even in the fall.”

As of 2018, Casella, Gonzalez, Tirol, Oliver, Ouk, and Quigley remained on NYPD payroll. In December 2014, the 76th Precinct honored Quigley as Cop of the Month. More recently, an ongoing civil lawsuit named Quigley as a defendant in March 2019, when a NYCHA resident in Staten Island accused three officers of throwing him down a flight of stairs in his building and then arresting him on false charges.

The NYPD continues to organize stings to catch the clients of sex workers, among other efforts to crack down on prostitution. “Commercial sex work has proven largely impervious to punitive policing,” Vitale argued. “When you target the customers, you’re still driving the whole thing into the underground black market, which means that the sex workers are more vulnerable to exploitation and abuse.”

According to Gangi, “de Blasio and [Police Commissioner James P.] O’Neill could make an administrative decision to decriminalize sex work.” Disbanding the NYPD’s vice squad, which targets prostitution, would save money that could be used “to provide services and supports for sex workers who want it.”

100 years for Ronald Williams

Three years after the death of Tyjuan Hill, another shooting took place in Red Hook. On August 3, 2015, a Ford Explorer pulled up to 9A Dwight Street; its occupants exited the vehicle and sprayed gunfire before speeding away from the scene.

No one died, but the bullets caused one of the five injured victims (three women, two men) to suffer a miscarriage. The police attributed the incident to gang violence, a misdirected retaliation for an earlier shooting in the Gowanus Houses. They arrested a suspect the next day, on August 4, and arrested two more on August 5.

On August 25, the NYPD made a fourth arrest: 23-year-old Ronald Williams, who lived on Baltic Street. The four young men, facing charges of attempted murder, attempted assault, assault, and criminal possession of a weapon, allegedly belonged to the Gowanus-based “OwwOww Gang.” Assistant District Attorney Nicole Chavis prosecuted them in a joint trial in 2017, following Williams’s attorney’s unsuccessful petition for a solo trial.

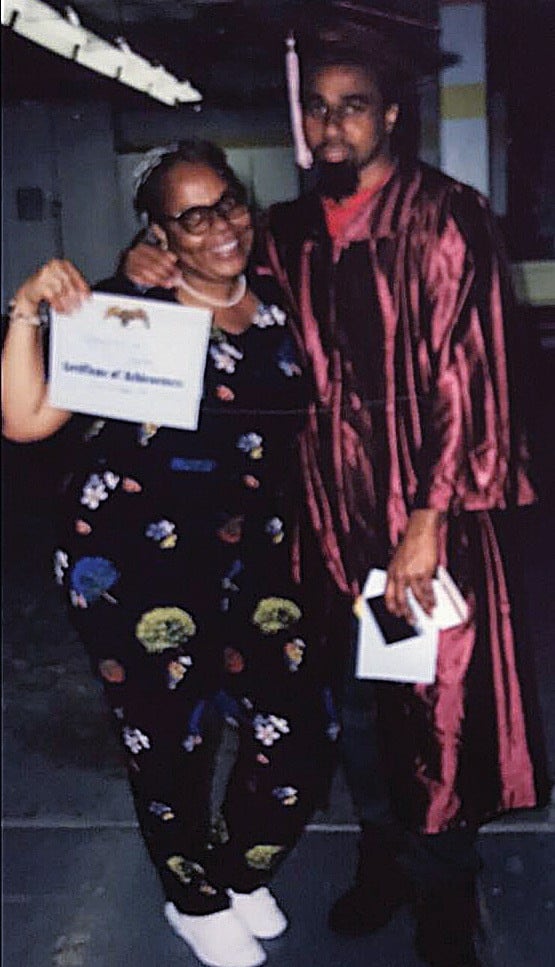

Two of the defendants were acquitted, and two were convicted. On July 6, 2017, a month after the jury turned in its verdict, Kings County Supreme Court Justice Vincent Del Giudice sentenced Williams to 100 years in prison. His rebuke of Williams appeared in the New York Daily News: “With your conduct alone, you have sworn your life away.” Williams maintains his innocence.

According to Williams, the NYPD targeted him during its investigation on account of a preexisting feud between him and the officers patrolling the Gowanus Houses, who had labeled him a gang leader. Like the Red Hook Houses, the Gowanus Houses sit within the jurisdiction of both the 76th Precinct and PSA 1.

[pullquote]“They’ve been constantly harassing him since his youth days.”[/pullquote]

“They’ve been constantly harassing him since his youth days,” his mother, Dianna Pippen, lamented. From Green Haven Correctional Facility in Stormville, New York, Williams described his experiences with law enforcement.

He doesn’t remember his first encounter with the police. But “once it happened, it just kept happening,” he said. Over the years, he was arrested on numerous minor charges such as marijuana possession and loitering in his own building.

He explained that, after the Gowanus Houses Community Center closed in 2006 or 2007, he and his friends had no place to hang out on cold or rainy days – they couldn’t all fit together in their families’ crowded apartments. When they congregated in his building’s lobby, the police suspected them of criminal activity.

Once, the officers promised trouble if they didn’t clear out. Williams and his friends scattered. “They chased everybody,” he recalled. Finally, when the scene had quieted, he tried to go home, but upon his return to the building, one of the cops threw him to the floor and jammed a gun to his head, leaving a bruise near his eye.

Another incident took place outside the front door to the family’s apartment, when an old friend, newly out of jail, came to visit Williams unexpectedly. They stood in the hallway chatting until an officer approached, demanding to see their IDs.

Williams, clad in pajamas and still wearing his PlayStation headset from inside, had no identification on him. But by Williams’s account, the officer already knew well from prior interactions who he was and that he lived only a step from where they stood: the only purpose of the questioning was harassment.

As the encounter grew more contentious, Williams’s friend fled. Hoping to avoid trouble for himself, Williams didn’t budge. Nevertheless, the officer handcuffed him and dragged him violently down the stairs in pursuit of the runner.

Cultural disconnect

By his own admission, Williams had taken part in some petty crime (“stupid little things”) during his adolescence, but by the time the shooting took place in 2015, he preferred to stay home and play video games. He had a steady girlfriend and an off-the-books job with a moving company.

In his telling, he never belonged to a gang. He blamed the misperception on a “cultural disconnect” between his community and the police, who “go by what they see on TV.” To them, an average group of friends might look like the Crips or Bloods if they were black and lived in public housing.

According to Williams, the “Oww Oww Gang” was an invention of the NYPD. The catchphrase “oww oww” had emerged from a popular song of the same name by the Brooklyn rapper Nu Money. Williams and his friends had adopted it for use at parties. But they had attended these parties to pick up girls, not to start fights: just the way it sounded, “oww oww” was flirtatious, not combative.

At the same time, real gang activity did exist in the Gowanus Houses, as did the gang warfare between Red Hook and Gowanus that had ostensibly prompted the 2015 shooting. In fact, one of Williams’s friends had died in an earlier shooting owing to the beef. But Williams believes that the 76th Precinct’s gang policing only exacerbated the tension between the two NYCHA developments, and the officers even appeared to take pleasure in doing so.

He said that, on days when they happened to have arrested gang members from both neighborhoods, the cops would deliberately put them in a cell together at the precinct, just to see what would happen. And when they charged a gang-affiliated person from Gowanus with a misdemeanor, they’d point out with relish that they’d have to go to court at the Red Hook Community Justice Center, which would mean entering enemy turf.

[pullquote]”We have some good people, and we have some bad people too. When we come home, we talk to people. We say hi. There’s nothing wrong with saying hi.“[/pullquote]

If Williams’s designation as a gang member owed to his proximity to those genuinely involved in gangs, it was only because the officers in his neighborhood didn’t understand the open nature of social life in the Gowanus Houses, according to Pippen. “My son is popular. When you live in a housing development, everybody knows everybody, and a lot of the people my son grew up with, they’d be outside. We have some good people, and we have some bad people too. When we come home, we talk to people. We say hi. There’s nothing wrong with saying hi.”

Once Williams had become a person of interest for the NYPD, he found that he attracted attention whenever he went outdoors. When police cars passed by, the officers would turn on their megaphones, blasting a public greeting: “Hi, Ronald.”

They especially liked to bust Williams for riding his bike on the sidewalk between his building and the street. One time, Williams was riding his bike in the street when a squad car came up behind him and began to tailgate him so closely that he became uncomfortable and pulled onto the sidewalk to let the officer pass. Then the squad car stopped, and the officer got out to arrest him for riding his bike on the sidewalk again.

In the middle of August in 2015, the police arrested him one last time on the same charge. He went home the same day, which wasn’t unusual. Pippen remembered that, when the charges against him were clearly “bogus,” the court would sometimes let her son – by then a familiar face – out the backdoor without an arraignment.

The prompt release in this case struck Williams as strange only after, a week or two later, the police had arrested him for attempted murder. This time, they brought a SWAT team to his family’s apartment.

Pippen answered the door and gave permission to the officer in front to come inside in order to show her a warrant. He replied that it would violate protocol for him to enter alone, so she invited one more officer to accompany him. Once the two had entered, the rest of the team burst through the door with guns drawn and shields up. Storming the apartment, they found Williams, but not before traumatizing Pippen’s younger son and her daughter, by the mother’s account. Pippen never saw the warrant. The officers would later claim that she’d let them in willingly.

In custody, Williams found out that one of the victims in the Red Hook shooting had identified him earlier in the month from a photo brought to her by the 76th Precinct. In the story eventually put forth by the police, the identification had taken place not long after the incident, before Williams’s arrest on the bike.

What Williams would come to believe was that the police had pressured or coerced the witness to ID him, and this process had taken some time, which accounted for the considerable gap between Williams’s arrest and his codefendants’ – in Williams’s theory, the police later shortened the timeline to make the accusation against him more credible. Having recognized the incident as a gang shooting, the 76th Precinct seemed to have determined to tack onto the indictment as many of the Gowanus Houses’ “gang members” as possible.

Out of five victims, only one placed Williams at the scene of the crime. Her testimony, which claimed that she’d seen four shooters on Dwight Street, differed from the other accounts, including those of independent eyewitnesses, which described only two shooters at the scene.

At the trial, the victim asserted a long familiarity with Williams, claiming that in her childhood she’d seen him meet the three other assailants outside her middle school on a regular basis. Williams emphasized the improbability of this arrangement, citing the four-year age gap between himself and his codefendants, who were roughly the same age as the witness. As he put it, 16-year-olds don’t hang out with 12-year-olds, who register as “little kids” to a high-schooler. By his account, he had never met the victim prior to his arrest.

Pippen, who works in administration at the New York City College of Technology, had spent her savings, which she’d hoped to use to move her family out of public housing, on a private attorney for her son. Del Giudice dismissed the lawyer from the case, however, on charges of tampering with evidence, based on what Williams called “triple hearsay.” On a phone call to Rikers Island, which records inmates’ communications, “my girlfriend said to me that my mother said to her that my lawyer said to her that I should deactivate Facebook,” Williams recounted.

The judge argued that this constituted an attempt to delete evidence. According to Pippen, the lawyer had wanted only to protect Williams from the snooping of the media, which often uses Facebook pictures to paint defendants in an unflattering light during trials related to violent crime: recontextualized, group photos become gang portraits. Williams noted that his Facebook page – whose contents he assumed the prosecution had already downloaded in their entirety – contained no information related to the case, and that deactivation doesn’t permanently delete Facebook data anyway.

288 Hamilton Avenue, site of Tyjuan Hill’s death.

Nevertheless, the court assigned Williams a public defender, and the judge afforded a one-month delay for preparation. Williams’s previous lawyer immediately made his files available to the new attorney by way of a Dropbox link and subsequently deleted the folder from the file-sharing website. Weeks later, during jury selection, the first lawyer received a request from the second to put the files back online, which made the former wonder whether the latter hadn’t bothered even to download the case file until the last moment.

Williams’s new lawyer proved unable to influence the judge on two crucial points. First, Del Giudice had excluded from the trial a DNA swab of the Ford Explorer, which had found none of Williams’s genetic material. Second, he had prohibited the introduction of early statements given to the police by Williams’s codefendants, due to an NYPD violation of New York’s right-to-counsel law during questioning.

Court documents indicate that two of Williams’s codefendants made “inculpatory statements” to the authorities immediately following their arrests, implicating themselves, each other, and the third codefendant in the shooting in some fashion. The statements never mentioned Williams, who made no admission of guilt or involvement upon arrest. (If Del Giudice had granted Williams a separate trial, the statements, which the judge ultimately dismissed as hearsay, could have been admitted without endangering the other three defendants.)

Before the trial, Williams rejected a “global plea deal” – requiring the consent of all four parties – that, by his account, his codefendants had been willing to accept. “I never even considered to voluntarily take jail time for something I did not do,” he said.

Lawrence P. Labrew, an attorney who successfully defended one of Williams’s codefendants in the joint trial, expressed his belief that Williams had had no connection to the incident: “My understanding is that he wasn’t even there.”

Gang policing

Throughout the trial, the prosecution highlighted Williams’s supposed gang connection, put forth by the NYPD, as a means to signify both his inherent guilt and the need for a harsh sentence. By multiple accounts, Chavis’s team presented inadequate evidence behind the claim of gang membership. In Williams’s words, “they just said it,” again and again.

In his aforementioned book, Vitale contended that the NYPD’s expanded gang suppression techniques emerged as a way for the police to continue to target New Yorkers of color once political pushback had taken away the wider net of stop-and-frisk. Under de Blasio, the police built gang databases, which allowed them to pinpoint particular individuals within low-income communities for the sort of invasive treatment previously applied more broadly under Bloomberg: “In both cases, black and brown youth are singled out for police harassment without adequate legal justification because they represent a ‘dangerous class’ of major concern to the police.”

Williams’s story anecdotally supports this theory. He attested that, in the year or so prior to his arrest for attempted murder, he’d noticed that the police had been stopping fewer of the young people in his neighborhood. “I was always the exception,” Williams related. Evidently, he’d made it into the gang database.

“We’ve seen a gang database intake form, and it says crazy stuff like ‘Wears certain colors’ – like red, blue, white, brown, purple, pink, yellow, orange,” Vitale revealed. “People can end up on the database in many ways. The police interrogate young people and try to get them to admit to it. They’re surveilling young people’s social media posts. If they’re Facebook friends with people or appear in photos with people, they’re considered potential gang members and get put on the database. 99 percent of the people on the city’s database are people of color.”

[pullquote]“There can be many problematic consequences. Folks find that they’re subjected to intense surveillance.“[/pullquote]

When someone ends up in the database, “there can be many problematic consequences. Folks find that they’re subjected to intense surveillance.” The NYPD uses the security cameras at NYCHA developments to conduct gang investigations, he said. “They’re sitting in there, watching what everyone is doing on the playground, who they’re talking to, et cetera.”

If arrested, suspected gang members can be “subjected to higher charges, higher bail amounts. If they are convicted of something, it sometimes results in enhanced sentencing. Also, they’re just more likely to get arrested or to be treated differently in routine traffic stops.”

Gangi echoed Vitale: “We at PROP would not immediately accept an NYPD designation that someone is in a gang, given what we know about how the gang database is created and how it operates. We’re convinced that it has a lot of people on it who are not active in gangs.”

Currently, Williams’s family is raising money on the website Fundrazr to hire a private appellate lawyer who’ll work to overturn the verdict against him. As of this writing, they’ve gathered $6,851 of a $15,000 goal.

The 76th Precinct declined to comment for this story.