35mm black and white film photographs by Piotr Pillardy

35mm color photographs by Joan Ronstadt

(developed & scanned at Exposure Therapy in Brooklyn)

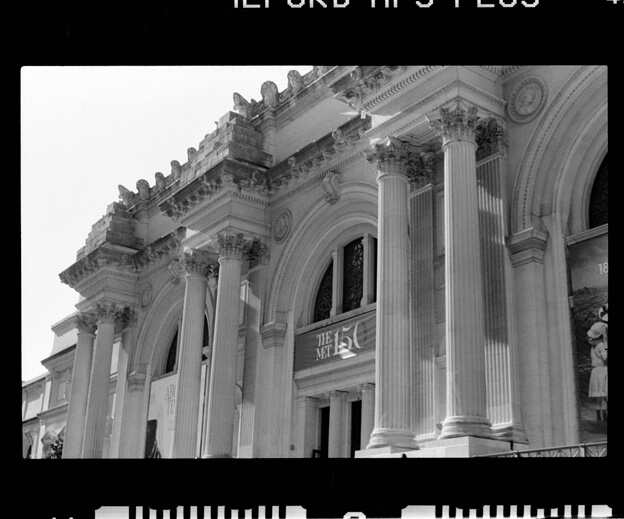

For the first time since February, during a year that has felt somehow infinite and compressed, I was able to visit a museum in person (a sentence that exists only in 2020). Going to the Met felt like a breath of fresh air after the long absence of this important and routine part of my life. In some ways, it felt normal, a facsimile of the “before times.” In others, it was a continued reminder of the ongoing pandemic, with exhibitions closed due to lack of ability to safely distance and the omnipresent masks.

As part of the new safety precautions, the museum has capped attendance at 25% and required masks worn inside at all times. This resulted in a long line out the door with dots on the ground to ensure proper distancing. However, the line moved pretty quickly and wasn’t too much of a hassle. It seems that if you buy a ticket online, you can bypass the line. I opted to reserve an hour long time slot to visit but this was not checked at the museum. It’s worth noting that certain special exhibitions sell out quickly due to the capacity restrictions, so it’s worth getting the tickets online ahead of time. A lesson learned as I was unfortunately not able to see the show “About Time: Fashion and Duration” because of this (which runs through February 7, 2021). So I would recommend getting tickets ahead of time if this or any other special exhibitions are your primary reason for visiting.

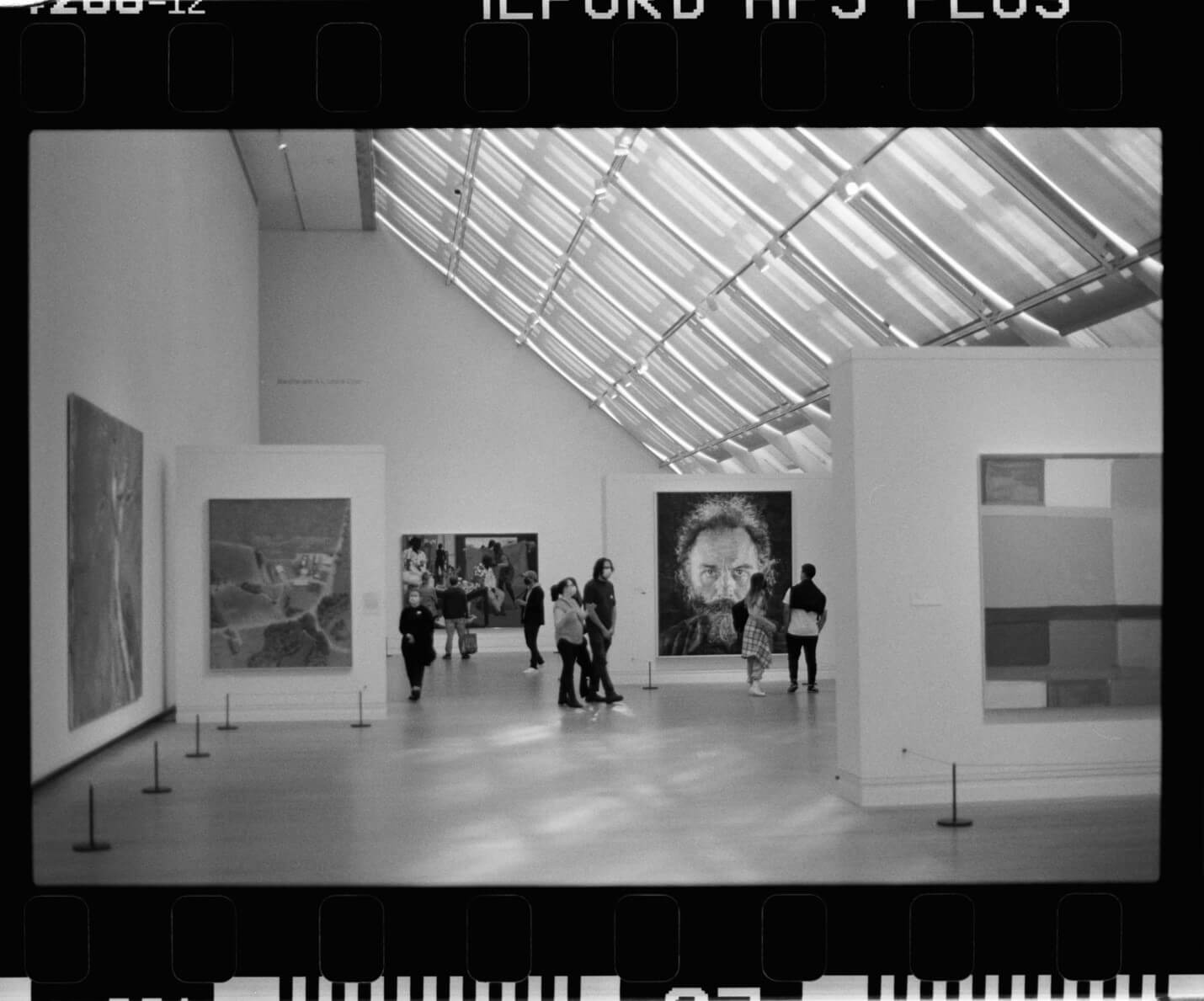

After checking in, I leisurely strolled through the halls of one of my favorite museums, thrilled to be reunited with old friends. It was great perusing the European and American painting collections and getting to see one of my favorite Monet paintings, Garden at Sainte-Addresse (1867), along with the great collection of works by El Greco, and the many abstract works from artists including Jackson Pollock, in the “Epic Abstraction” portion of the permanent collection.

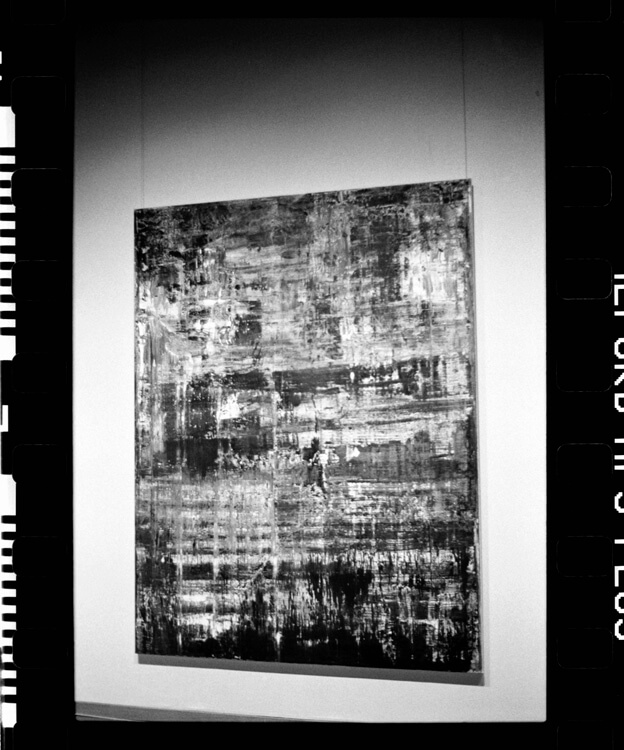

Upon entering the Robert Lehman Collection, I was pleasantly surprised to stumble upon a small Gerhard Richter exhibition. The exhibition, featuring 4 paintings from the artist’s Birkenau series along with an earlier sculptural work, had served as the basis of the Richter solo exhibition at the former Met Breuer, which closed a few days after opening due to the pandemic. The show was not rescheduled and now, even the Met Breuer itself is a thing of the past. The Frick Collection will temporarily be taking over the space as that museum undergoes an extensive renovation, where it will be through 2023.

The artist’s series, exploring issues of history, memory, and identity, draw its inspiration from four secretly-taken photographs from the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camps. Created in Richter’s signature abstract style, the painting creates a meditative moment with the viewer, allowing one to consider the underlying subject matter in the absence of representation. Richter had actually embarked on a yearlong attempt to render the photographic figures from the photographs, but ended up gradually obscuring them through numerous layers of paint squeegeed to produce his well-known style. These themes are further present in the earlier work included at the beginning of the small exhibition, Mirror, Blood Red (1991), a work that confronts the viewer and allows for a brief moment of reflection prior to consuming the context behind the exhibition.

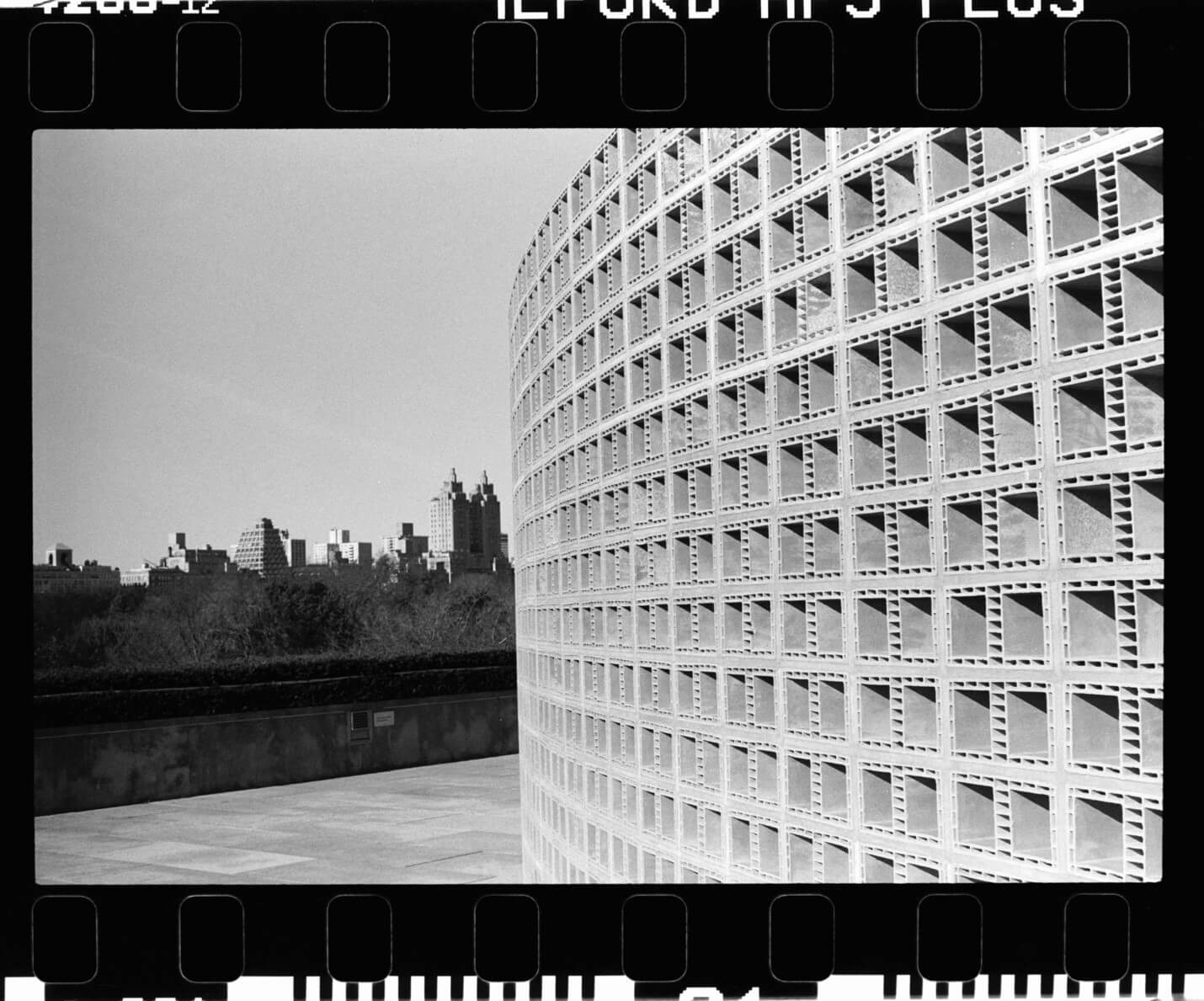

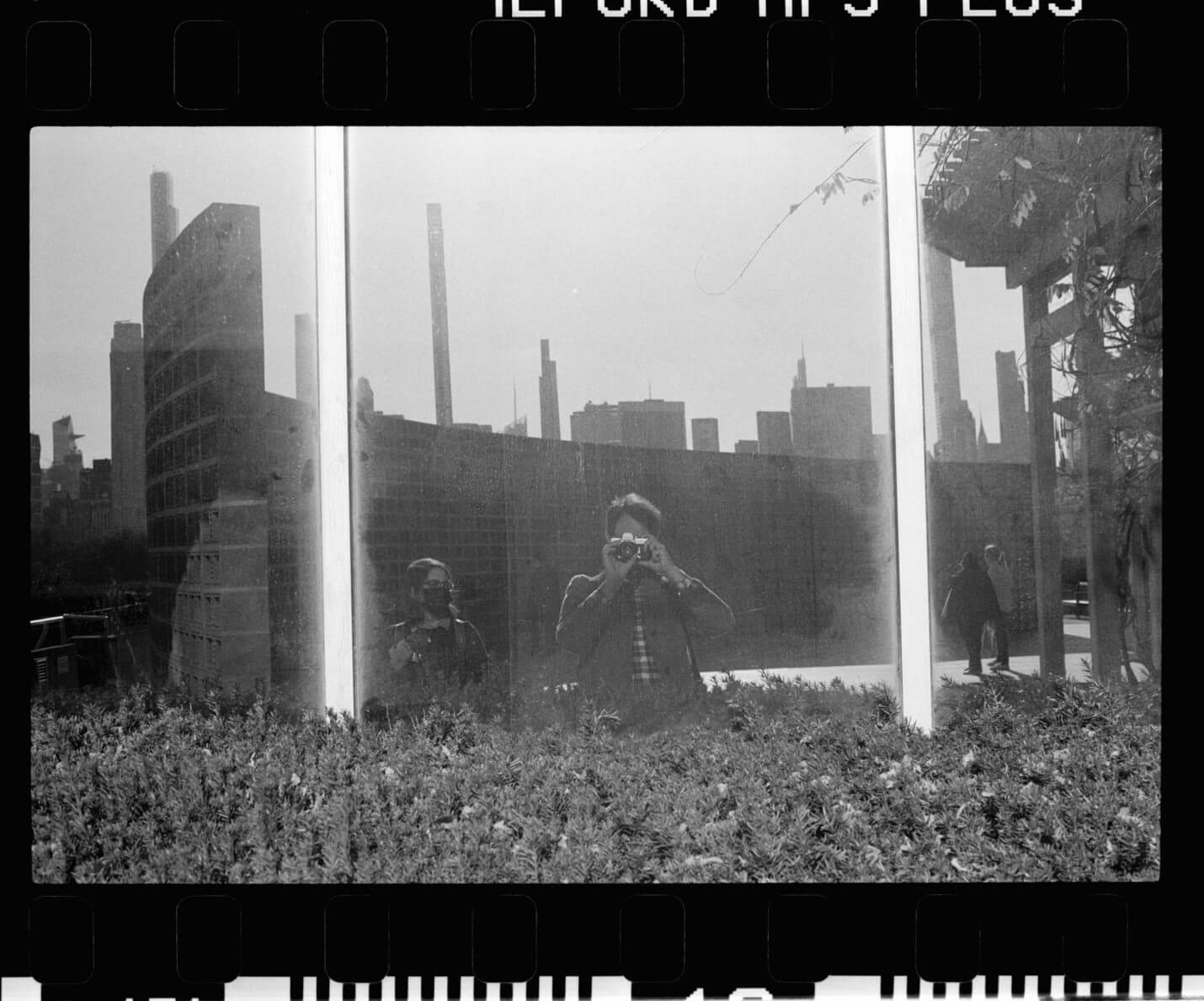

Another highlight of the visit was the, always wonderful, yearly Roof Garden commission (in its eighth year) that presents a site-specific work framed by sweeping views of Manhattan’s East and West sides. This year Héctor Zamora’s Lattice Detour (2020) was the pick, a curved sculptural terracotta brick form. The work’s strength lies in its ability to frame and contextualize numerous interactions between visitors in the space, iconic views, and light itself. Being both solid and permeable, the sculpture bifurcates the physical space while allowing for interactions. In many ways, the piece reminded me of the Dan Graham’s Hedge Two-Way Mirror Walkabout installation from the 2014 commission, which allowed for similar moments of interaction with the space and those inhabiting. In our current COVID reality, the barrier acts as both an artistic device while helping physically separate one from other visitors in both a tangible and intangible way.

Zamora, whose work typically engages with public spaces, chose the Met’s Roof Garden because it is the museum’s only public open space. The artist had the audience in mind when fabricating the piece to allow for interaction with the views. The terracotta bricks used for the piece also have significance. The materials subvert expectation through being presented in a curvilinear form, in contrast to the stark rigidity typically associated with bricks, themes explored throughout his oeuvre including Material Inconstancy (2012) and Uma Boa Ordem (2019). The allusions to labor in the piece are also important since bricklayers created it by hand, as well as symbolically signifying the divide between the United States and Mexico. On a more aspirational note, the work’s lattice structure allows the viewer to see the light on the other side and can serve as an example of seeing past these divisions in the world to explore other points of view. Zamora’s piece is only up until December 7th, so see it while you still can!

Another highlight of the temporary exhibitions were the two photography shows, including Photography’s Last Century (which closed on November 30th) and Pictures, Revisited (which runs through May 9, 2021). The former was a powerful survey of 20th century photography, with works from artists including Man Ray, László Moholy-Nagy, Diane Arbus, Andy Warhol, Sigmar Polke, and Cindy Sherman. The latter explored contemporary photography and the interactions between the medium and appropriation. The works here manipulate elements of pop culture to subvert, decontextualize, and provide commentary on these famed images burned into our collective conscience.

With all of these great exhibitions and many more in the pipeline, it’s a great time to pay the Met a visit. With vaccines on the horizon, there is hope that how we interact with artistic institutions too will return to normal in the not so distant future. However, even being able to visit The Met again under these conditions was a delight.

The Met Fifth Avenue’s iconic façade

Héctor Zamora’s Lattice Detour (2020) with view of the west side of Manhattan

Héctor Zamora’s Lattice Detour (2020) and its interactions with light

Héctor Zamora’s Lattice Detour (2020) seen in full in window reflection

View through Héctor Zamora’s Lattice Detour (2020)

View through Héctor Zamora’s Lattice Detour (2020)

Birkenau (2014) by Gerhard Richter

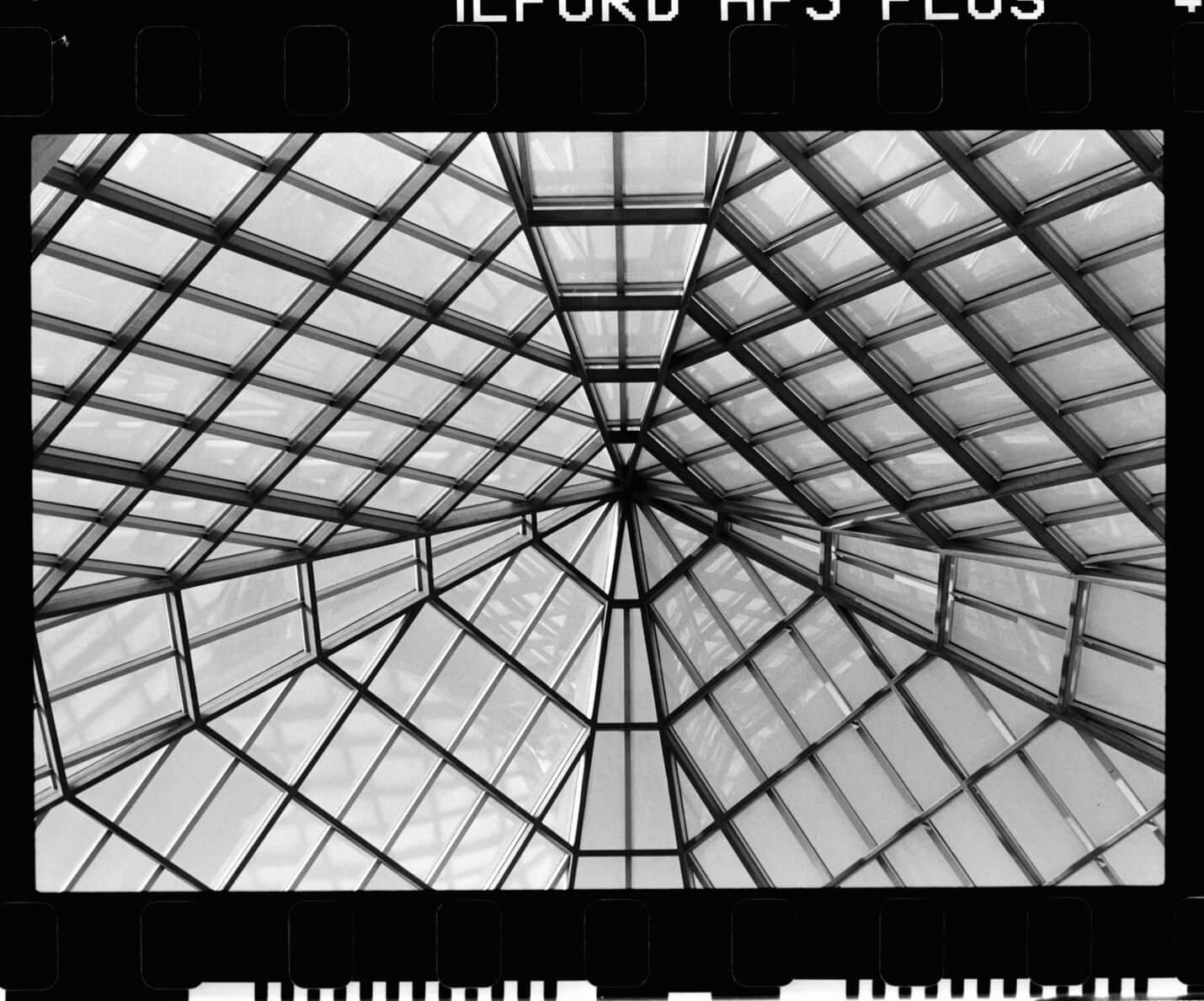

Glass canopy above the Robert Lehman Collection

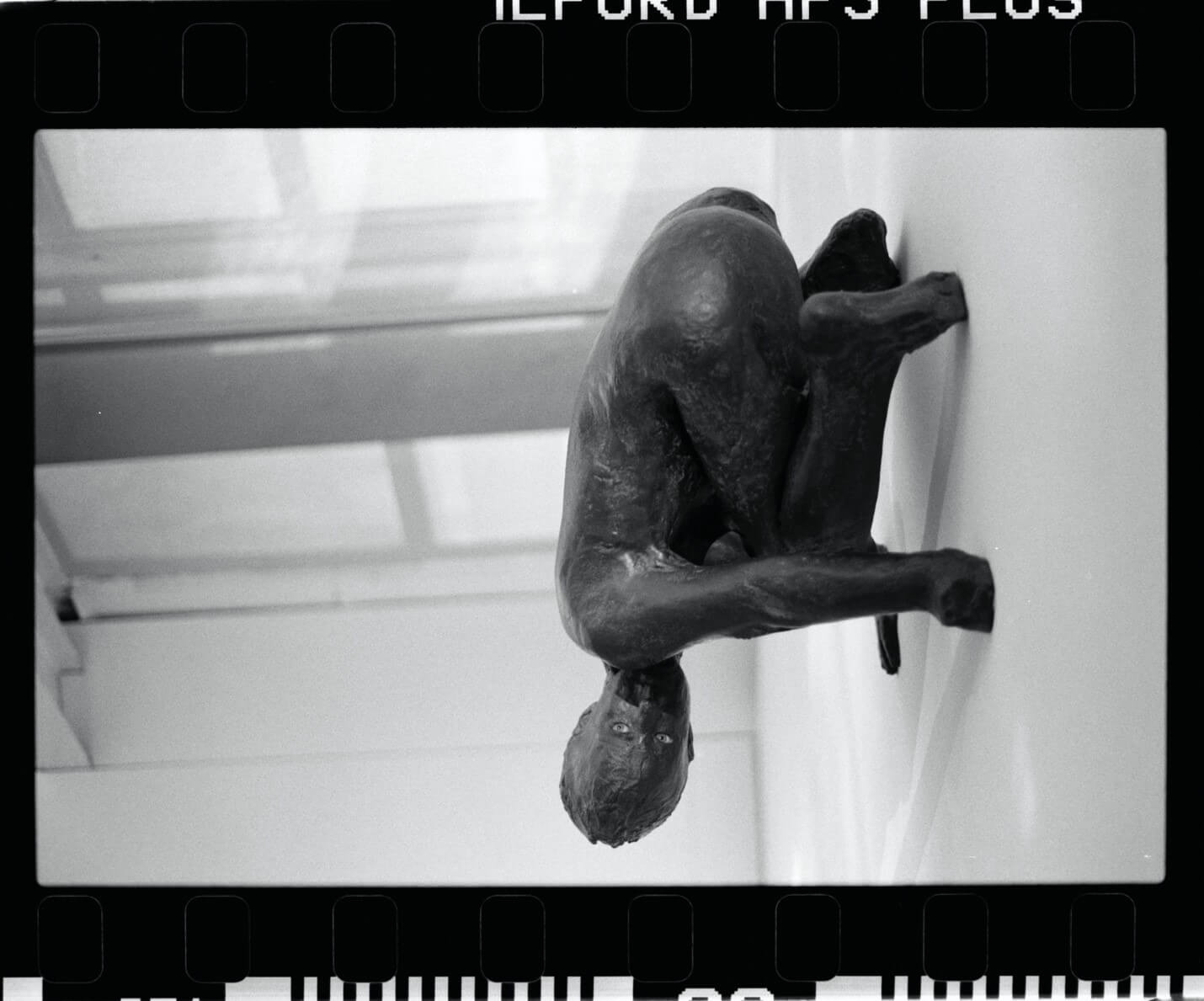

Lilith (1994) by Kiki Smith in the Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera exhibition

Antonio Canova’s Perseus wiith the Head of Medusa (1804-6)

Exhibition view of “Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera”

Author

-

Piotr Pillardy is an arts/music writer for the Red Hook Star-Revue. He received a BA in History of Art and History from Cornell University and lives in Brooklyn

View all posts

Piotr Pillardy is an arts/music writer for the Red Hook Star-Revue. He received a BA in History of Art and History from Cornell University and lives in Brooklyn