Lindsay LeBorgne is a fourth-generation Local 40 ironworker and Brooklynite with roots in the Mohawk communities that stretch along the border of the United States and Canada. His grandfather worked on the first generation of skyscrapers in New York City. And Lindsay’s father worked on the original World Trade Center. After 9/11, Lindsay worked long shifts in the rubble of the site, cutting down and removing the steel, searching for victims. And their remains.

Although more commonly known as Mohawk, Lindsay’s people call themselves Kahnawake, which means “People of the Flint.” Mohawk derived from “Mohowawogs” meaning, “man-eaters,” a name derived by a neighboring Indigenous tribe from New England. Early Dutch colonists heard the word as Mohawk.

“Where in Brooklyn did you grow up?” I asked Lindsay.

“On State and Bond Street.”

[slideshow_deploy id=’13013′]

I told Lindsay that I’d lived only a few blocks away in Carroll Gardens about twenty years ago.

“Were there a lot of Kahnawake people in Brooklyn when you were a kid?”

“Let’s put it this way,” said Lindsay. “My building had twenty apartments; eighteen of those apartments were occupied by Kahnawake families. And there were pockets of Kahnawake all around the neighborhood. In fact, many people were all related. But distantly. They used to call it Little Kahnawake, or Downtown Kahnawake after the Kahnawake reservation in Canada.”

“Why were there so many Kahnawake living in Downtown Brooklyn?” I asked.

“My father was born on the Kahnawake Reservation in Canada. Like many Kahnawake, he drove down every week from the reservation to work on the skyscrapers. This was before the New York State Thruway. It took him maybe six to eight hours to drive down and back up. As you can imagine, this was painful.

“Like most men on the Kahnawake Reservation in those days, my father would be gone from Sunday night to Friday. He’d come back to the reservation on the weekends. Eventually, he moved to Brooklyn so he could take the train to work. One stop to Wall Street.”

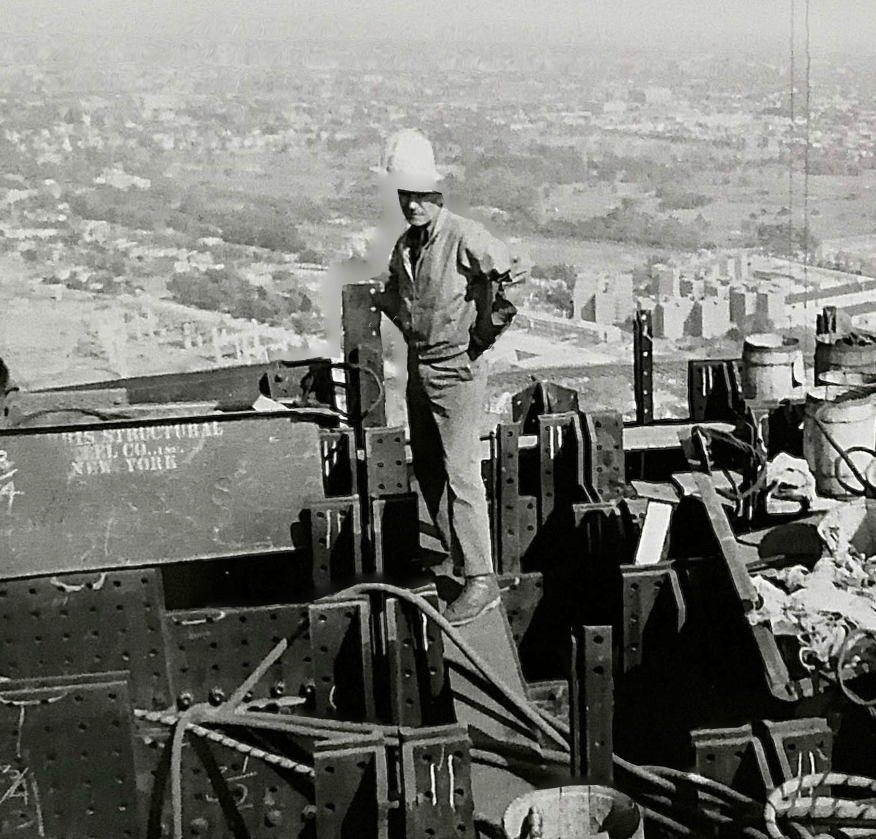

“I saw the pictures of your father on various New York City skyscrapers. He was on the crew that built the World Trade Center?”

“Yes, he was. Funny thing is my father said that people didn’t want to work on that building. The company demanded too much overtime. Many out-of-towners worked on the Trade Center. We called them boomers. Quebecers, even people from other countries. You could make up to one hundred dollars a week.

“This is all we knew. Don’t forget my father’s father worked on the skyscrapers. This was our thing.”

“I see the pictures of you and your father high up on those rigs and I get woozy. I’ve heard that Kahnawake were hired to work on the skyscrapers because they seemed to be unperturbed by heights. Do you know why that is?” I asked.

“I’ve heard that before too,” said Lindsay. “But the truth is, I really don’t know why. I wasn’t necessarily afraid of the heights, but I respected the situation. I was more worried about dropping something and injuring or killing someone.”

“I never even thought of that,” I said.

“And besides, I’ve fallen before. And have been injured in the past.”

I learned afterwards that starting in the 1850s, Canadian construction companies began building bridges. The precious stone materials that were needed were found on the Kahnawake reservation.

As such, they required the approval of Kahnawake chiefs to quarry stone found on the reservation.

Having paid for the stone, the men of Kahnawake were also then paid to transport stone and materials.

According to Kahnawake elder, Tom Diablo, during the building of the Victoria Bridge, Canadian workers seemed very scared walking on the narrow girders. Watching them build the bridge, young Kahnawake men easily scaled the beams, seemingly unaffected by the heights. This was noticed by the team of Canadian builders. Kahnawake were then hired by the construction company.

Working with the rigs, whether on bridges or buildings, requires a high level of skill and knowledge.

In the early days there weren’t many scientific instruments to determine the structure and chemistry of the materials. A lot depended on instinct and experience. Imagine being high on a rig, way above the ground. First you must be able to walk on the steel planks without losing your nerve. Then you have to be able to manage the operations of working with steel girders. The Kahnawake men recruited their sons at a young age to train as apprentices and gain precious experience. In a few generations, the Kahnawake developed a reputation for being skilled ironworkers and their services were in high demand.

“And I grew up with rigs all of my life. I was accustomed to it. This was our lives,” added Lindsay.

“Do you speak Kahnawake?” I asked.

“No, I don’t. My grandparents spoke Kahnawake, but they decided at a certain point not to speak the language. There were penalties for speaking our language. It wasn’t just discouraged; it was outlawed.”

In 1924 Congress finally granted Native Americans the right to vote with the passing of the Indian Citizenship Act. But since voting rights were governed by states, it wasn’t until 1957 that all states were forced to comply. Until that time, not only were Native Americans denied voting rights, but they were also considered wards of the state and were denied basic rights, including the right to travel. Wards of the state? The people who were born on this land.

“But I have good news,” said Lindsay, “my daughter speaks Kahnawake fluently.”

“What religion do you practice?”

“I’m a Catholic. My wife is Catholic. We were raised as Catholics.”

“Do you practice the Kahnawake religion?”

“I don’t see our traditions as a religion; it’s more of a practice. We are people of the longhouse. We have ceremonies for the moon, for growing seasons, and so on. I believe in a creator. We have creation stories that we tell our kids. One god. One creator. We were taught respect for animals, and for the land. I totally get it. It makes perfect sense to me.”

“Where do you live now?”

“I live back on the Kahnawake Reservation in Canada. It’s our community – only Kahnawake. This has been a Kahnawake settlement for over four hundred years. We get up to 8,500-9,500 people here in the summer. People bring their families.”

“What’s your role in the local government?”

“I’m a Council Chief. There are twelve of us; one is Grand Chief. The eleven other chiefs divide up segments of the community. We each have three different portfolios, like health, archeology, etc. We attend meetings, argue with the government,” said, Lindsay, laughing. “We’re a microcosm of every other government.”

“What do you hope to see as a future for the Kahnawake people?”

“I’d like our views on the environment to be more embraced by all governments. I’d also like all Indigenous American people to be more visible to the world.”

“What do you mean by more visible?”

“Most people don’t know history. Our history in the United States. Not just the horrible stuff, but the wisdom that’s been handed down from generation to generation. How to preserve the soil, the air, and the waters. We’re sometimes only visible as sports teams.”

“What change would you like to see going forward in this country?”

“My hope is that our history, our knowledge, doesn’t just fade away. My children know more about our history than I do.”

I thanked Lindsay for taking the time to talk to me. I have to admit that I felt close to his story.

Listening to Lindsay repeatedly reminded me of my Southern Italian American family. From the time they arrived in America to the nineteen-sixties, they, the Southern Italians, all lived together in Downtown Manhattan, sometimes in the same apartment building, but never too far from each other. They were also blue-collar workers. And due to their darker color and the fact that they were Catholics, they were excluded from certain jobs. And they were shamed into losing their language.

But of course, although there were many similarities, there were many significant differences. There may have been signs that read No Italians Need Apply, but there weren’t laws on the books making it illegal for Italians to speak their language or practice their religion.

In whatever small way that I can, I hope to keep his history, the family’s history, and the history of the Kahnawake people alive and visible.

New York Ironworkers

https://www.6sqft.com/men-of-steel-how-brooklyns-native-american-ironworkers-built-new-york/

Skywalkers: The Legacy of the Mohawk Ironworkers at the World Trade Center

http://www.melissacacciola.com/#/heinrich-harrison/

Kahnawake Tourism

https://kahnawaketourism.com/

Mike Fiorito

www.fallingfromtrees.info

https://www.pw.org/directory/writers/mike_fiorito