When Melvin Van Peebles moved from San Francisco to Hollywood to make movies in the late 1950s, Tinseltown power brokers took one look at the young Black Air Force veteran (and director of a few short films) and offered him a job — running an elevator. When he pushed for something more, let’s say, creative, they said he could be a dancer. He said they could go fuck themselves.

[slideshow_deploy id=’13371′]

Van Peebles soon decamped for Europe after someone at the Cinémathèque française saw his first three short films and invited him to France, where he wrote three novels and earned a temporary permit to direct films. He promptly adapted one of his books, La permission, into a feature, which got Melvin Van Peebles on Hollywood’s radar — for the right reasons — and ignited a trailblazing career that included Watermelon Man (1970) and, a year later, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, ground zero for blaxploitation.

He only directed four more features through 2008, and for many moviegoers the Van Peebles name might be familiar because of his son, Mario, a brilliant actor and director (New Jack City) in his own right. But American cinema — mainstream, independent, and otherwise — would be a very different place without Melvin Van Peebles, a multi-hyphenate Renaissance man whose films, often featuring all- or majority-Black casts, are racy, raw, and alive to the world, often unflinching, occasionally uncomfortable, and always entertaining.

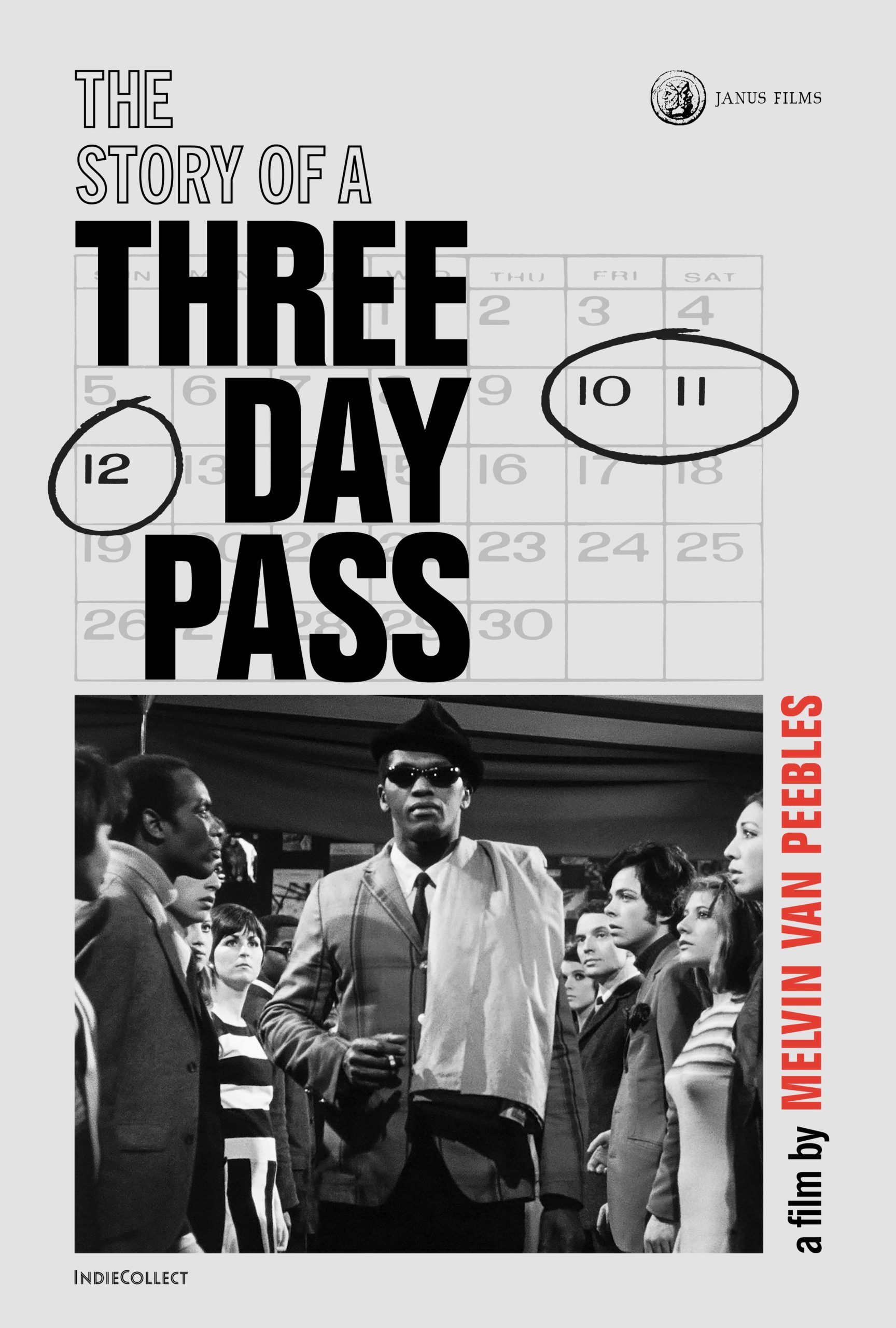

Sweet Sweetback will undoubtedly be his legacy, but none of Van Peebles’ career would have been possible if not for that first feature, the French-made adaption of La permission, The Story of a Three Day Pass. Released in 1968, it has existed in recent years as a cult object, difficult, if not impossible, to see in anything but grainy, copy-of-copy bootlegs. But thanks to a new 4K restoration by IndieCollect, supported by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association and supported by Van Peebles, Three Day Pass can be rightly given the consideration and due it deserves. (New Yorkers comfortable with returning to movie theaters can see it in its ideal presentation during a run at Film Forum that opens May 7.)

At 87 minutes, Three Day Pass is a lean film, focused on a Black American serviceman, Turner (Harry Baird), given a three-day leave as a reward from his paternalistic captain for being promoted to “Assistant Orderly.” Stationed in France, Turner naturally takes off to Paris, where he wanders in an alienated remove, hits up a nightclub, and meets the similarly disaffected — and very white — Miriam (Nicole Berger). The English-speaking Turner and French-native Miriam awkwardly connect over the course of the night and decide to spend the weekend together in Normandy, where they make love, have fun, and pledge grand promises to one another about their lives together once the pass expires and Turner returns to base.

It’s the kind of loose narrative that scaffolded much of the French New Wave, and like Godard, Truffaut, and Rivette, Van Peebles uses the story’s openness to experiment with form, style, and time. He makes liberal use of the jump cut. He leans so hard into splicing together different perspectives of the same interaction that the scene could be a Futurist painting come alive. He places dialogue and narration over shots of bucolic nature, views of the road from inside moving cars, and languid ocean vistas from beaches and bluffs. He even cast a New Wave star, Berger, who broke through in Trufaut’s Shoot the Piano Player, in one of the major roles.

There are times when Three Day Pass feels oppressively indebted to the New Wave — the nightclub scene where Turner and Miriam meet comes instantly to mind, which is propulsively jazzy, jumpy, and Godardian. But unlike an acolyte leaning on movement grammar as a crutch his first time out, Van Peebles wields it with confidence, if not always precision. There are numerous moments when a scene begins a frame or two too early or the montage is a bit creaky, but those stand out less as mistakes and more as the kinds of seams that show when shooting on a tight schedule and tighter budget. And while they can be distracting, they don’t distract from Van Peeble’s burgeoning virtuosity.

Back to that nightclub scene. Turner enters as if he’s floating into a world swirling around him, a clear precursor to Spike Lee’s signature double dolly shot. It only lasts a moment and is a bit inelegant, but it’s dazzling all the same — especially because, in 2021, we know how that kind of shot will evolve and who will come to own it. Once Turner’s at the bar, he spots a woman he imagines falling in love with, and Van Peebles shows Turner’s spirit leave his body and move toward the woman’s table as the mass of clubgoers parts like the Red Sea. Later, when Turner is back in his hotel room, Van Peebles pulls an unexpected and audacious trick. Turner lays on his bed, a neon sign blinking oppressively in the dark room; the lighting shifts to indicate morning; and, in two shots stitched together to create the illusion of a single take, Van Peebles swings his camera in a semicircle to show Turner get up, change clothes, gather his bags, and walk out the door to meet Miriam. Whether done as an experiment or out of cockiness, the shot is something of a breathtaking showstopper.

That New Wave spirit permeates the whole of Three Day Pass, even when it slows down after reaching Normandy. (Van Peebles crafts a sweet nod to French cinema past and present when Turner and Miriam ride on the back of a farmer’s hay wagon; the couple, looking like they stepped out of Masculin Féminin; listening to a philosophical farmer who could have stepped out of a Jean Renoir work.) But the film isn’t an empty experiment by an expat in Paris, nor is it an existential treatise on ennui and the hopelessness of love in a conflagrated world. For one, the film is far more sardonic — more Ishmael Reed than Albert Camus — than anything you’ll find in the New Wave canon. But more importantly, Van Peebles directs all those jump cuts and time loops and direct audience addresses toward a confrontation with the signal concern of his career: race.

Turner and Miriam are indeed doomed lovers, but not because the universe is conspired against them — they’re condemned because he’s Black and she’s white. When Three Day Pass was released in 1968, the concept of a Black man and white woman romantically engaged, never mind the actual sight of a mixed-race couple together, was the height of scandal. Van Peebles pushes it further by showing the couple in bed, naked, together, before, during, and after sex. They confess their undying love, but there’s never any question about what will happen to this union by the end of the film. Instead, lingering over it like an acid mist is what will lead to the inevitable dissolution. Is it the self-loathing voice in Turner’s head, calling him an Uncle Tom for being in the Army or perpetually preparing him for disappointment? Is it the internalized racism of Miriam, who imagines, during their lovemaking, that she’s being taken by an African tribesman complete with a bone in his afro? Is it the institutional racism of the flag Turner has pledged to defend — the captain who looks at Turner and sees little more than a dim child; Turner’s white Army buddies shocked at the site of Miriam and Turner together; the scenes of Jim Crow protesters we see flash through Turner’s thoughts?

The answer is yes. For Turner, race isn’t something you overcome; it simply is. And it’s complicated by the differences between the racism Turner experiences everyday as a Black American and the way it manifests in an old-world nation like France. At one point, Turner gets fights a Spanish singer in a restaurant after he thinks the singer calls him the n-word. (It’s a question of the singer using the Spanish word for “black,” but even this is freighted by Van Peebles with layers of interpretation.) Turner’s ready to fight to the death, but Miriam soothes him and guides him toward the hotel, telling him the singer was trying to be complimentary. As the scene ends, Turner says, “How can anyone think that Black is a compliment?”

More than 50 years later, that line still lands like a haymaker. And for all its scrappiness and roughness, so does The Story of a Three Day Pass. Sweet Sweetback might be Van Peebles’ calling card, but his first film throbs with the energy, potential, and fuck-you-Hollywood attitude that birthed not only his career but a universe of possibility in American cinema. It’s impossible to imagine Spike Lee, John Singleton, Robert Townsend, or, indeed, Mario Van Peebles without Melvin Van Peebles. And it’s impossible to imagine Melvin Van Peebles without The Story of a Three Day Pass.

The Story of a Three Day Pass opens at Film Forum on May 7

Note from Dante: I wanted to let you all know about something I’m really excited about: the new podcast I’m co-hosting. It’s called CINEOPOLIS, and it’s all about movies and the places that made them. I’m doing the show with my good friend Christian Niedan, and the first episode — all about the seminal NYC joyride DIE HARD WITH A VENGEANCE — dropped today. There are 10 shows in all in this first season, which also includes deep dives into THE FRIENDS OF EDDIE COYLE, the films of George Romero, and Christopher Nolan’s Gotham City, as well as four interviews about movie places and spaces.

Christian and I did a couple episodes of another movie podcast — about SWEET SMELL OF SUCCESS and LAST ACTION HERO — which led to CINEOPOLIS, an idea that grew out of our mutual and individual work writing and thinking about cinematic cities and architecture.

You can find more about CINEOPOLIS, including how to subscribe (please subscribe), on its show page. It has been a blast doing these shows, and I hope you enjoy listening to them! Let me know what you think, and thanks for indulging.