David Lynch is a problem. A big one. David Lynch is a problem because he doesn’t punish his villains. He’s a problem because he doesn’t explain the motivations of his villains or even so much as resolve his stories. David Lynch is a problem because he won’t tell us what to think of him.

Storytellers runs the risk of being seen as complicit with, or at least indifferent to, their villains if they don’t take a moral stand in the telling. This is a problem for white men in particular, by virtue of their inheritance of the mantle of power. This is a problem that leaves Alfred Hitchcock open to criticism of his 1960 film Psycho for telling a story about a man who assumes his dead mother’s identity in order to kill other women. This is a problem that leaves Steve Reich open to criticism for sampling and repeating the voice of a black man beaten by police in his 1966 composition Come Out. It’s also a problem that makes those works possible. Not taking a stand is a privileged position. A value-neutral film Spike Lee film about race relations would just seem weird.

This is an essay by a white man about an issue that effects women, but it’s also an essay about another white man whose art addresses sexual violence in ways both disarmingly direct and unnervingly abstract. This is an essay about an uneasy relationship with fandom, made possible by a book a woman wrote about a man who addresses sexual violence through his art.

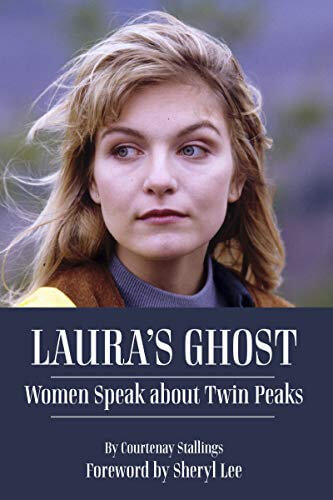

Courtenay Stallings spoke with fans, critics and people who have worked with for Laura’s Ghost: Women Speak About Twin Peaks (being published October 20 by Fayetteville Mafia Press). The ghost is Laura Palmer, around whose death Lynch’s Twin Peaks television serial (1990-91), the 1992 prequel film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me and the 2017 third season Twin Peaks: The Return revolved. The interviewees—as the title proclaims, all women—include Sheryl Lee, who played Laura, and Grace Zabriskie, who played Laura’s mother. Both speak highly of Lynch, as does every other interviewee in the book. This is not surprising; Laura’s Ghost is in some respect a fanzine. But it’s not only that. Some of the women in the book (including the author) speak of their own histories of trauma, and speak of the catharsis they found in Laura’s story. They may not have encountered the evil spirits that inhabit Lynch’s imagined Pacific Northwest, but they’ve experienced the trauma. (A portion of proceeds from book sales will go to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network.)

Twin Peaks is modern day mythology. It’s an invisible realm of supernatural beings invented to explain evils that can’t otherwise be explained. Lynch is the mythmaker. (As a storyteller, he has a talented collaborator in co-writer Mark Frost, but Lynch—as evidenced by his other works—is the dreamer). The world in the fable is one where people are basically good. Violence is brought into this world by otherworldly spirits. The violence depicted isn’t comic book tableaux. It’s not Tarrantino cool. Twin Peaks is an attempt to explain the unexplainable. It’s an invention to explain how a man, himself a victim of childhood sexual abuse, can rape his daughter and how his wife can live in the house knowing it’s happening. It’s a mythology devised to symbolize intergenerational sexual abuse. How do we explain the unexplainable? By positing spirits and deities. How can we explain humans who commit inhuman acts? We can’t, at least not in any sensible way

I have thought many different things about David Lynch since Twin Peaks first aired, and even before. I was entranced by his depictions of the darknesses hidden in American middle-class enclaves. I was later alienated by his casting the same scrutiny on Hollywood and the movie industry. The Return brought me back into the fold. It made the Laura Palmer saga into an epic triptych, spanning half my life and played out as quirky comedy, crime drama, supernatural science fiction and art house cinema. The shifts in style between Twin Peaks, Fire Walk With Me and The Return made it a narrative of Falknerian proportions.

That, at the most basic level, is what The Return meant to me. But just as the secrets of the storyline are for each viewer to decipher for themselves, the significance of the tale itself, the way in which it’s received, can dramatically. For the women in Laura’s Ghost, it’s a story of the abuse that happens to women, and the silence under which it’s often endured. The pain is real, the violence is visceral. It can be extremely hard to watch the brutality against women Lynch puts onscreen, and charges of misogyny aren’t hard to understand. Film critic Marya E. Gates addresses such charges in Laura’s Ghost: “There is a perception by some that Lynch is misogynistic, but I don’t think that’s accurate. […] The thing about Lynch is not that he hates women. I think he’s acutely aware of the violence that women face, both emotional and physical. I think he’s not afraid to show that. […] He’s so great at showing emotional violence and not afraid to show you that when these people are out in public, they may be perfectly fine, but behind everything the emotional violence is so deafening.”

As human as his stories can sometimes be, though, Lynch deals in types. He’s not interested in believable characters. He sometimes pushes his actors into absurd portrayals and other times gets painfully believable performances from them. His male characters are just as much types as his female. They are strong and assured or, if not, cry to show weakness. Lynch fetishizes a post-war, Norman Rockwellized and very Caucasian American Dream in order to disrupt it.

In season two of the original run of Twin Peaks, FBI forensics specialist Albert Rosenfield (played by the late Miguel Ferrer) speculated about the unknown evil they were investigating. Maybe, he said, it’s “the evil that men do. Maybe it doesn’t matter what we call it.” The line pivots on patriarchal language. Is it the evil that mankind does or the evil of the males of the species? The raw facts of the story, and of the real world, suggest it’s the latter.

For further consideration on Lynch’s problems with race, see “What Does David Lynch Have to Say About Race? In the filmmaker’s vision of America, whiteness is the source of all evil” by Frank Guan in the Vulture and Niella Orr’s “It Is Happening Again: David Lynch’s ‘Twin Peaks’ returns—to its white fantasia,” both from 2017

For further reading on Steve Reich’s Come Out, see Ellen Y. Tani’s “Come Out to Show Them”: Speech and Ambivalence in the Work of Steve Reich and Glenn Ligon,” published December 23, 2019 in Art Journal Open.

2 Comments

Do bad guys really need to be punished in fiction though? Because they don’t get punished most of the time in real life. So to me, it makes sense that they don’t get punished all of the time in Lynch’s world. He does punish his villains some of the time though, like in Blue Velvet or Inland Empire. I liked you article though, it had an interesting take on Lynch.

Spike Lee’s movies routinely are value neutral in regards to race. Like Malcolm X for example, very matter of fact biopic, but there’s a total lack of politicking on Lee’s part. You aren’t told how to feel about black nationalism, NOI, anything. It is frustrating.

But lynch is doing a similar thing. He’s diving into his subconscious and putting these characters onto film, he’s just reporting the facts man.