“We came up from the subway / On the music midnight makes / To Charlie’s bass and Lester’s saxophone / In taxi horns and brakes.” – Joni Mitchell

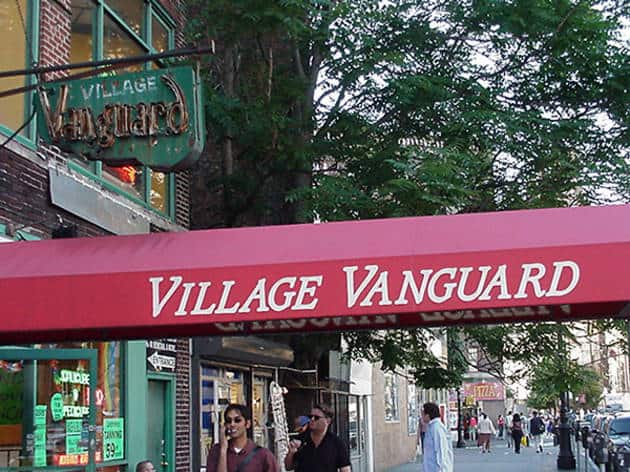

Take the 1 train to Christopher Street and walk uptown on Seventh Avenue South for a few blocks and you end up in a rough triangle marked by Smalls, Mezzrow, and the Village Vanguard. You go down steps to get into each of these basement jazz clubs, where you’re likely to be knee-to-knee and elbow-to-elbow in a way that would make that subway car seem roomy.

These clubs have been off-limits since mid-March, and it’s impossible to see them reopening until there’s a vaccine for COVID-19. This is a jazz problem and also a music problem, a math problem and a physics problem: how many tickets can you sell for a set at the Vanguard and how much will they be so working musicians and staff can get paid and the club can have some profit to pay the landlord and the utilities bills; and how do you devise an HVAC system to keep pumping fresh air through the room, because a group of people breathing in a small, enclosed space is a dangerous proposition.

And how do you charge a premium ticket in a county where unemployment is around 20 percent at Memorial Day (and most likely undercounted) and unemployment benefits are set to run out without any reasonable expectation of an extension on the horizon? Put it another way, how does jazz work in a de facto neo-feudal political economy?

Yes, this is a music problem but especially a jazz problem. Not only is the market for the music so niche-like as to constitute a cult, but the jazz musicians who can make a living without doing non-music jobs depend on live music situations. Those are jazz gigs, of course, but also playing in pit bands on Broadway, touring with popular music acts, teaching, recording for other musicians’ albums or arranging music for other performers. Without the constant flow of live situations, there’s very little to do, and without listeners buying records (if you like a record, please buy a copy!), streaming revenues are so infinitesimal that they show services like Spotify have contempt for music, seeing it as a loss-leader for “content” like Joe Rogan.

That is just another landmark on the decades-long journey wherein talk has replaced music as the broadcast content of choice. I don’t understand it and I can’t figure it out. Media surrounds us already, and given that it’s all talk – strange how news in the visual medium consists of watching someone sit at a desk and talk – about politics and crime and maybe books and movies, the desire to consume more and more talk seems bizarre. We make music too, in some ways we talk with music, and there has to be some alternative to the constant, repetitive yammering. The great keyboardist Joe Zawinul once said something to the effect that he used synthesizers along with the piano because he loved potatoes, but he didn’t want to eat potatoes all the time, every day, only potatoes.

And there is why, for the first time in my 40 years of playing jazz, studying jazz, writing about jazz, I’m genuinely worried about the music. Since its drastic commercial decline in the 1960s, it’s managed to hang on economically while growing artistically in an inspiring and majestic way. But if musicians can’t get a gig, any kind of gig, they have to find another way to survive. The top-down money is guaranteed to exist – just as the human inclination tends towards hierarchies and authoritarianism, so there will always be rich lords who wish to impress the peons with their good taste and largesse. But that money will continue to go to the Lincoln Centers of the world, places that serve institutionally acceptable entertainment to people who seek to be flattered for their own values and sense of importance. That Lincoln Center is a literal blighted sepulcher right now, a tomb ironically emptied because to fill it would be to infect it, will in no way deter funders from tossing their money that way a year from now.

In that year, from June of this to May of next, many places are going to disappear. How many doesn’t matter so much as that, in this center of the jazz universe, city of eight million people that never sleeps, there’s not that many jazz clubs – again, the musicians are most often playing other gigs. If in the Seventh Avenue South triangle, Smalls and Mezzrow close and the Vanguard remains, that’s a huge loss. While the Vanguard-style full-week engagement is great, so is the fact that a club can have a different act every couple of nights. There’s already a surplus of good musicians out there, so losing a couple dozen sets a week means that at least a couple dozen musicians aren’t playing.

Jazz is tied up to this country as one of the few truly original, 100 percent American things, and one of the greatest things civilization has produced. More, it’s tied to the mess of history – without the Civil War and Emancipation, there would be no groundwork for the music. Segregation also formed the ideas and styles in no small part, and the sheer beauty and excitement of the music had no small part in fueling the civil rights movement. Before rock, soul, and hip-hop, jazz was reflecting the times, and the chaos of the 1960s shattered the musical landscape as it did the political and social.

Now we’re at the end of empire, at the edge of collapse of a decadent late-capitalist system. If people can’t work, they can’t make money, and without money they can’t churn through the endless cycle of consumer goods and services that have had America treading water for 50 years. It’s an intensely important topic, one worth talking about, but maybe all we have left is talk.

Author

-

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/

View all posts

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/