In 1901 the wealthy John J. Snyder Jr., age 38, wed the wealthy Lillian Emma Rich, age 26, daughter of Theodore Washington Rich, the wealthy former trustee of Bixby & Co, a nationally famous shoe polish firm that became insolvent in 1895. Rich was also an officer of the Flatbush Press Co, which soon became insolvent. But Rich remained rich. Apparently, Rich had an insolvency-proof gene, possibly attributable to his surname. In any event after their marriage John & Lillian Snyder bought a new wood-frame detached home on East 18th Street in Beverly Square East, possibly built with Ross & Snyder lumber (see Part 2), and plumbing fixtures supplied by Snyder’s of Flatbush (see Part 1). There, the newlyweds would spend their next three decades together.

John Jr. served for many years as Vice-President of the Flatbush Taxpayers Association, consisting of 800+ homeowners who seemed to be perpetually aggrieved about a lack of services from Borough and City institutions. The owners were overwhelmingly Republican, and the political leaders were mostly Democrats so that might have played a role. Snyder, of course, owed his prominence to the fabulously successful hardware stores his family had established over the previous decades. He became a fierce advocate for Flatbush on a variety of transportation issues, but none of them came to pass.

A Utica Avenue subway to serve transit deserts from East Flatbush to Jamaica Bay garnered much support, as it still does today, without success. More fanciful was his proposal to build a highway atop the LIRR freight line from Bay Ridge northeast to Sunrise Highway, an idea ever so briefly revived by the Lindsey Administration’s 1970 “Linear City” proposal. Noting the steady increase in car ownership and the lack of parks, he urged that basement parking garages and rooftop playgrounds be required for all new apartment houses. He argued that an expanded Floyd Bennett Field should become the City’s lone municipal airport. Disappointed by the lack of civic engagement as the ranks of the Taxpayers Association dwindled, he suggested voter apathy could be combatted by hiring vaudeville entertainers to perform at the polls. And as cinemas sprouted up all over Flatbush, he also campaigned against “depravity and licentiousness” in the movies, although it was unclear at times whether he meant on the screen or in the aisles.

In 1930 the 68-year-old Snyder retired from the hardware business and three years later, his wife Lillian passed away. The ground floor of the Snyder Avenue store continued to sell some hardware under new ownership and Snyder held onto an office there, where he would routinely entertain reporters looking for a story about “the olden days,” as he wound down his stewardship of the Flatbush Chamber of Commerce, concentrating now on turning out a new “Flatbush Magazine.”

Snyder consented to the 2nd floor of his building becoming a “Socialist Meeting Hall” in 1931. But a Detective at the 67 Precinct down the block didn’t take kindly to Erasmus kids passing out Socialist leaflets in front of the Hall, so he arrested them, took them to the basement of the Precinct and beat them senseless, eventually serving three years in prison for the assault. After that, Snyder devoted the 2nd floor space to an amateur dramatic troupe.

[slideshow_deploy id=’14276′]

Yes, times were changing, but Brooklyn old-timers couldn’t get enough of Snyder’s tales, so he devoted the last decade of his life to collecting stories about the Flatbush of his youth. As he aged, John Snyder would increasingly be described as an historian and then eventually as the “Mayor of Flatbush,” even after selling his house and moving to an apartment on Bedford Avenue, off Clarendon Road. In 1945 he self-published his stories in a marvelous book filled with old photos and illustrations, Tales of Old Flatbush (two copies yet survive in the Brooklyn Public Library’s Grand Army Plaza branch and another at the Brooklyn Historical Society on Pierrepont Street). His life’s work complete, he died the following year.

But before we go, I need to point out that other people have been dubbed “The Mayor of Flatbush” over the years, ranging from Brooklyn Dodger fan favorites to a depression-era street peddler insisting on diplomatic immunity as he was being arrested because others considered him their Mayor. In the most recent and saddest example, a striving Rasta-Man videographer, known to many in his realm as the Mayor of Flatbush, was gunned down in 2019 by a teenage Crip in a Flatbush Avenue bodega for failing to smile sweetly or something…

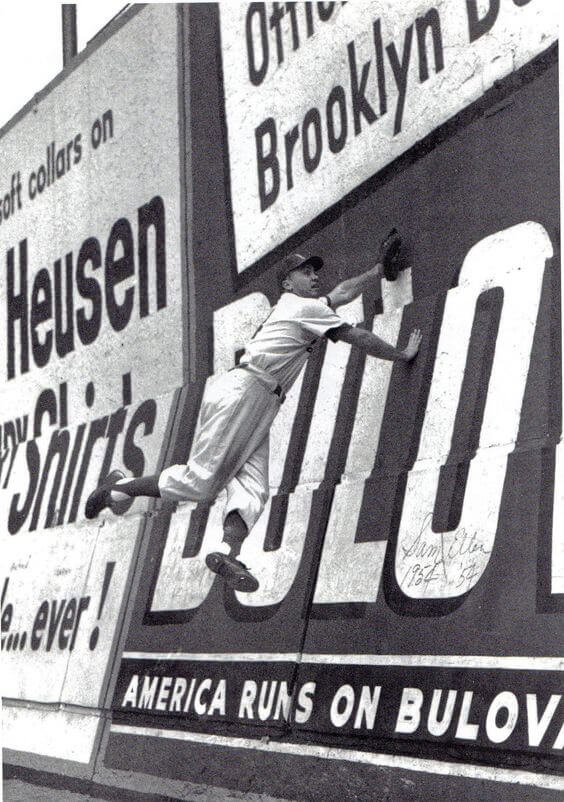

But. There was only – and ever will be – one Duke of Flatbush. And if you lived as we did, right off the corner of Flatbush Avenue, how could we have any other hero but Duke Snider? He was so graceful and regal in his premature gray hair, batting lefty and hitting over 40 homers for five years in a row in an age when ball players worked other jobs to make ends meet.

Yet, my father was a Giants fan who was fond of saying Willie Mays was the best ball player he ever saw, “and that includes Ruth, Cobb, Williams, Mantle, Snider and ANYBODY ELSE YOU’D CARE TO MENTION,” he’d interject before you could counter. But none of his nine kids followed him into Giants’ fandom. Instead, we all rooted for the Brooklyn Dodgers, who were only two miles away. Duh.

Duke Snider was my Willie Mays.

The night my father died I had a dream. It was a cold, drizzly late afternoon at the end of the season and Duke Snider was playing center field at Ebbets Field again. The game was meaningless because the Dodgers had been eliminated long ago and there were very few people in the stands. But the Dodgers were winning this final game, against the Phillies, by a run. The scoreboard had posted two outs in the 9th inning and the Phillies had the bases loaded. I hated the Phillies. Some things never change.

In my dream, Duke crouches in center, waiting for the pitch. It’s raining harder, the field is starting to look muddy. The Dodgers are leaving Brooklyn after this game I hear somebody say. The batter swings and all the runners take off. The ball is hit high and far, way over Duke’s head, but he gets a great jump. Running full tilt, even as he sloshes through the warning track, the Duke leaps, his body fully extended and erect, his immaculate white uniform framed against the drab black wall. He makes the catch but as he does, his body takes the full impact of that hard, unyielding wall and he slumps to the ground, lifeless, but still clutching the ball.

I woke up crying from my dream about Duke Snider. Of course, I realized I was crying for my father. We didn’t have much of a relationship until his last months when I visited him in a nursing home off Francis Lewis Boulevard, not too far from Shea Stadium. And we would always talk about baseball – the only topic we never fought about.

My father taught me how to catch and took me for long walks on Sundays after church to watch fast pitch softball games in East Flatbush at what we called “The East 40th Street Park.” And now he was gone. The season was over, the house where we all grew up was gone, like Ebbets Field and the Polo Grounds. And the Duke was dead.

My father, like the Duke, had his moments of grace that I never forgot. Like the time he took us for ice cream – me and my twin sister and Bobby, a six year old who spent weekends and summers with us, temporarily rescued from an orphanage while my parents tried to figure out how to adopt him. As if they didn’t already have enough mouths to feed on a single civil service salary. As we crossed Flatbush Avenue, my father took Bobby’s hand and told him not to let go. “Yes, Daddy,” Bobby said. This affectionate tableau was not lost on a big brute of a man, crossing in the other direction, who glared at Bobby, a dark-skinned Hispanic kid holding my father’s hand, and then growled at my father “Nigger lover!” My father ignored the brute and shouted in a loud voice, “Look, Bobby, the ice cream store’s open! Let’s all get some!” And the four of us were soon a-swim in cones.

I can’t help but wonder when I’ve played my last game, will my son remember any moments of grace I might have summoned in his presence?

2 Comments

The Duke was special — but so was your father. Thanks for writing this nice piece Joe!

Wonderful