When we last left the Dukes, patriarch John Jacob Snyder straddled a hardware empire in a once sleepy Flatbush that was now busting its britches. All thanks to technology.

Since 1878 the Brighton railroad, created by Flatbush Dutch potentates to feed northern Brooklyn vacationers from Prospect Park southward to the Dutch Masters’ hotel in Brighton Beach, had been chugging into Church Avenue, its first stop, four blocks west of the Dutch Reformed Church at Flatbush Avenue. Then in 1883 the Brooklyn Bridge opened and provided the first rail link to & from Manhattan, thanks to elevated lines that linked to cable cars over the bridge.

But the 19th Century trains were all steam-driven, slow and sooty, until 1900 when they became electrified thanks to new-fangled overhead wires attached to trolley poles. This innovation sped access for the well-to-do City folk now gobbling up the detached homes rapidly replacing farmland south of Prospect Park. A train of new “suburban developments” rumbled toward the seashore: Prospect Park South, Beverly Square, Ditmas Park, South Midwood, Midwood Park, Fiske Terrace, West Midwood were all erected between 1900 and 1905, producing thousands of new customers for the growing commercial hub surrounding the old Church. By the time Papa Snyder passed on in 1908, eulogized as “one of the oldest residents of Flatbush and until 10 years ago, the only German occupant,” there were three “Snyder’s of Flatbush” hardware stores he bequeathed to his sons, Alexander (born 1855), John (born 1862) & Phillip (born 1870).

Phillip The Youngest Snyder became the manager of the shop at Flatbush & Clarkson Avenues and in 1895 he hired a young blonde lass named Florence Louise Robinson to keep his books. Florence lived in an apartment alongside the Long Island Rail Road tracks on Atlantic Avenue, not far from today’s Barclay Center. Her dad didn’t have much of a commute to get to work since he was a flagman in the sprawling LIRR trainyards nearby.

As it happened, Phillip Snyder was a Lieutenant in the 13th Regiment of the National Guard, headquartered just a few blocks from the Robinsons in an armory at Atlantic & Flatbush Avenues (razed in 1906 to erect the LIRR Terminal building). Whether Lt. Snyder first chanced upon Florence in those noisy environs and offered her a job is lost to history. What we do know is that love bloomed amidst Snyder’s nails and screws because Phillip & Florence set a marriage date for August 27, 1895.

But Phillip hid the betrothal from his parents, sensing their disapproval of his fondness for a girl they considered far below his station.

“Marry the daughter of a soot-covered flagman? Hah! Why, the very idea!”

So, Phillip got cold feet and literally left Florence standing at the altar. And that’s where things got interesting. Fearing the fury of a woman scorned, the next day the wealthy Phillip transferred all his property to his oldest brother and plotted his flight to an unidentified Western town. “Not so fast, bub,” Florence declared, and her employer was arrested on a bench warrant for “breach of wedding contract.” Phillip was dragged before a Kings County Supreme Court judge and the Brooklyn press got busy.

Florence’s suit asked for $25,000 (almost $900,000 in today’s coinage). However, even then, the wheels of justice ground slow: the matter did not come to trial until February 1897. After Phillip and Florence testified, the jury deliberated for less than an hour and found Phillip incredibly guilty, although it did reduce the award four-fold.

But wait, there’s more! After the verdict Phillip and his siter Nellie announced that they were going to marry Frances and Daniel Esquirol, respectively, in a double wedding ceremony come the Fall of 1897. The Esquirol family lived in a fancy house a block from Phillip’s store and were just as loaded as the Snyders. Flatbush society rejoiced!

Ah, but alas, Phillip, still smarting from his public humiliation, and worried that Florence would show up and cause a commotion at a public service, convinced his betrothed to wed him in a private ceremony on August 5th, attended by only two witnesses and a preacher. So, if you’re keeping score at home, that’s two secret August weddings for Phillip, two years apart, but only one consummated.

As Fall in Flatbush waned and the New Year arrived, ushering in the “The Great Mistake of ’98” – the wedding of Brooklyn and the three other outer boroughs to Manhattan to form a new New York City – Flatbush caterers wondered, “How come we’re not getting any orders for that Snyder-Esquirol wedding extravaganza?” An intrepid reporter finally uncovered the shocking truth of Phillip’s private ceremony, compounded by the doubly shocking revelation that his sister and her Esquirol fiancée also went the super-duper-secret-wedding route in December!! Caterers were bummed. Then finally, the triply shocking news – lovely Florence was marrying her childhood sweetheart over by the wrong side of the Atlantic Avenue tracks!!!

Was everything going to end happily-ever-after? Not quite, because now the Manhattan press began competing with their Brooklyn brethren for the next headline in this continuing soap opera. The frenzy caused Phillip to suffer what appears to have been a nervous breakdown, although the attending physician described it as mere “cerebral congestion.” Papa Snyder, minding Phillip’s store at 765 Flatbush Avenue on February 7, 1898, was asked by a reporter for his take on the family drama and replied: “The wedding came before we expected it, but it is all right. I told Phillip to take life easy for a few days.”

[slideshow_deploy id=’14067′]

Phillip recovered and quickly returned to work but – I am not making this up – he immediately ABANDONED his no longer secret wife, Frances Esquirol. She then hired Frank Harvey Field, the same attorney who represented the jilted Florence, and sued for divorce. Scurrying into the Kings County courthouse one day, lawyer Field announced that the scoundrel Phillip, facing new alimony, had yet to satisfy the judgement he owed Florence.

Thirteen years later, Phillip’s abandoned wife Frances died at the age of 36 of Bright’s Disease. She passed away in the home adjoining the Esquirol estate on West Clarkson Street (now Woodruff Avenue) that, sadly, her father had built as a wedding gift. Meanwhile Phillip spent his remaining years managing an asbestos shingle business inside the Snyder hardware emporium at Bedford & Flatbush while residing in the family home on East 21st Street, overlooking what would later be designated in 1978 as the Albemarle-Kenmore Terraces Historic District. Following multiple strokes Phillip died in 1925 before he could re-re-marry.

Alexander The Eldest Snyder took a different path. Forsaking metal for wood, he bought into a lumber company on Union Street in Gowanus, owned by Sylvester Ross, forming the Ross & Snyder partnership in 1888. In 1903 Ross would build the still-standing four-story limestone mansion at the southwest corner of Carroll Street & Prospect Park West. Perhaps realizing he was not setting a good example for home construction from which he might benefit, Ross sold the mansion for an ungodly sum, leaving no doubt that lumber was becoming increasingly profitable, given the thousands of wood frame houses then being built in southern Brooklyn. Row houses were out. Peaked roofs, light and space were in.

Ross died in 1907, leaving the reins of the company to Alexander and his son, Frank (born 1884). Not long after, Alexander was elected VP of the Flatbush Trust Company and would remain an influential economic force in Flatbush until his death in 1923. Frank then expanded the lumber operation along 3rd Avenue, north of Union Street, but when the Depression hit, he relocated to a more affordable location on Douglass Street, east of 3rd Avenue. Alas, the firm became insolvent in 1937 and Frank became an “incinerator salesman.” Talk about burning your bridges! By 1947 Frank was renting an apartment in Fiske Terrace, sending reminiscences to the Brooklyn Eagle about old Church Avenue. He died hours after Jackie Robinson’s Brooklyn Dodgers won the fourth game of the 1947 World Series at Ebbets Field when Cookie Lavagetto famously broke up the Yankees’ no-hitter.

IN PART THREE: The Mayors and Royalty of Flatbush, including the Duke of Bedford Avenue.

1910 Flatbush & Atlantic

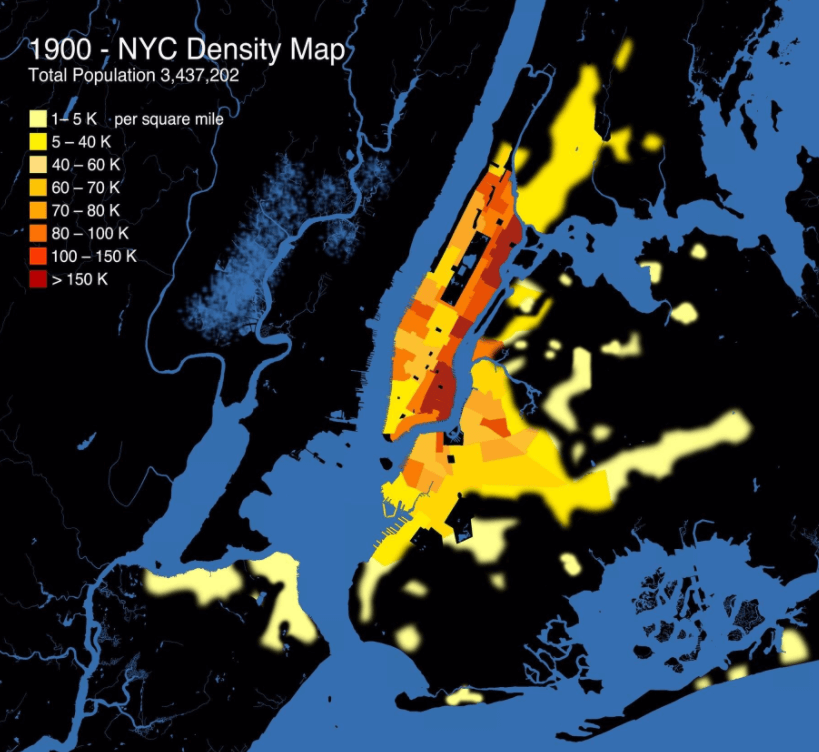

1900: Southern Brooklyn Is Black as Night

1914 Flatbush & Church Ave: Trolley Wires Gone Crazy

2021 Non-Ostentatious Snyder Plot in Green-Wood Cemetery