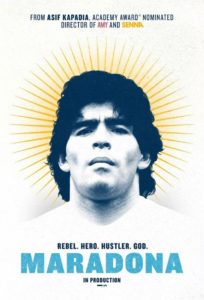

Diego Maradonna, the new film from Academy Award-winning documentarian Asif Kapadia, opens with a car chase. Two sedans speed through the winding streets of Naples, enclosed on both sides by throngs of football fans. As they holler and push against police barricades,adoration becomes indistinguishable from aggression. The sedans accelerate to escape this mass of suffocating love, and they nearly collide. It’s an exhilarating sequence, and the most telling visual metaphor in the film. In one car is play making demigod Diego Maradona, and he can only avoid the crash for so long.

It’s 1984. Maradonna is 23, and already the greatest soccer player in the world. He has already escaped the Argentine shantytown of his youth and taken the field for a rich European football club. Now, down-and-out Italian team SSC Napoli has purchased his contract. In Naples, he will attain his greatest professional triumphs and sink to his lowest personal despairs.

As with his previous films Senna and Amy, Kapadia attempts not so much as to explain his subject as to immerse the viewer in his life. Kapadia therefore forsakes a traditional documentary structure and its cast of dry subject matter experts. He never cuts away from archival footage to interview aging witnesses; instead, relatives, colleagues, and Maradona himself contribute ambient voice over that contextualizes on-screen footage.

Without the crutch of a talking head to explain Maradona’s brilliance, Kapadia leans on contemporary game footage, most of it shot from pitch level. Unlike television audiences at the time, the viewer sees the intricacy of Maradonna’s footwork, his breakaway speed, the tiny gaps he created in defenses before eviscerating them.

Kapadia highlights the grace of Maradona’s game, and reveals how this exercise in controlled explosiveness could move broadcasters to tears and supporters to blind worship. But for every successful feint, pinpoint cross, and miraculous goal, Kapadia includes a shot of enormous galoots knocking the 5’5” Maradona into the turf. Maradona’s beauty came at a cost, both in the form of physical injury and the uncontrolled explosiveness of his private life.

Using home video shot by Maradona’s first wife, newscast B-roll, and archival photos, Kapadia paints a portrait of an unraveling home front. Periodic images of an unacknowledged son remind the viewer of his failures as a husband and a father. Maradona begins wearing gold Rolex watches, gifts from his friends and benefactors in the Italian mafia. Party scenes, initially comical in their joviality, darken when narrators confirm that his sunken eyes and disheveled appearance signal a spiraling cocaine addiction.

Kapadia most insightful discovery, however, involves Maradona’s discomfort at his own canonization as a Neapolitan saint. In sequence after sequence, soccer fans crowd Maradona as he eats dinner, trains, and walks to team facilities. Though he pleads for the crowd to stop touching him, they grasp for their hero. Even police escorts clap hands on his back and shoulders. Maradona, Kapadia implies, became a public commodity; an inhuman icon to be seen, touched, and used by an Italian public uninterested in his private thoughts or desires.

However, access comes at a cost. By collaborating directly with Maradona, his family, and his supporters, Kapadia perhaps undermines his narrative independence. Kapadia frames Maradona’s descent into addiction, depravity, and crime as the result of a betrayal by the Italian public, for whom he sacrificed his body and his privacy.

This sympathetic, party-line narrative strays into the territory of hero-worship. Kapadia argues that Maradona’s fame stripped him of any shot at normalcy, but this overlooks Maradona’s considerable wealth and agency. Maradona chose to philander, chose to abandon his children, chose to associate with the mafia, and chose to play soccer. Kapadia should have interrogated Maradona’s destructiveness with the same rigor as he examined his brilliance, but chose not to. Kapadia, like so many before him, prefers Maradona the martyr to Maradona the man. It’s a fitting, if disappointing, conclusion to the story of a man who could never escape the weight of his own image.

Diego Maradona will be screened at Cinépolis Chelsea on November 8 and 12 as part of the DOC NYC festival. It is also available for streaming on HBO.

3/4 STARS