Carnivals and amusement parks have always held the allure of the illicit. Slightly malevolent barkers beckon you into sideshows promising thrills, chills, and horrors beyond your imaginations. Scantily clad acrobats, trapeze artists, and magician’s assistants infuse the atmosphere with sex and desire. Ragtag clowns wear lurid makeup that can never quite hide their I’ve-seen-way-too-much eyes. Creaky rides, seemingly always on the cusp of collapse, thrash you around tracks and drop you from great heights in what might very well be your last experience on Earth — and, of course, the operators are barely interested in your fate. And then there are the rickety haunted houses and halls of mirrors, the games designed to swindle your allowance, and food guaranteed to contract every single one of your arteries.

How could a director like George A. Romero resist such a place?

[slideshow_deploy id=’13485′]

In 1968, Romero created a new kind of horror cinema with his first feature, Night of the Living Dead. It established the grammar of zombies we still use more than 50 years later, and, with a budget of about $114,000, proved that Romero could deliver a huge return — in box office and scares — on a meager investment. And while Romero would have a major mainstream hit in the sequel Dawn of the Dead, in 1978, and he would complete 14 other features — including The Crazies (1973), Martin (1977), and four more Dead films — before his death in 2017, Romero had perpetual tough luck getting things made. The amount of material left incomplete, unrealized, or never funded far outpaces his produced work.

It’s in that trove where The Amusement Park, a 54-minute impressionistic piece of agit-prop filmmaking on the existential dread of aging, was found, forgotten and in desperate need of repair. Made in 1973 and screened at least once, the film was a favorite of Romero’s yet languished in obscurity. But after restoration work undertaken by the George A. Romero Foundation and IndieCollect, The Amusement Park received a limited theatrical release (begun at the Museum of Modern Art in 2020 before the pandemic shunted the rest of the run to 2021) ahead of its debut on the streaming service Shudder on June 8.

Looked at from a literal here’s-Romero’s-IMDb-listing view, The Amusement Park seems like an oddity. For one, it’s an educational film sponsored by the Lutheran Service Society of Western Pennsylvania highlighting the challenges faced by the nation’s elderly. It’s “the story of a universal man, symbolized as one who has recently retired, who goes out into the amusement park to find his happiness as an older citizen,” per the film’s promotional material. “As he travels through the amusement park, he begins to experience the reality of being old in a young society. He is cheated, degraded, beaten, ignored; he discovers what loneliness is.”

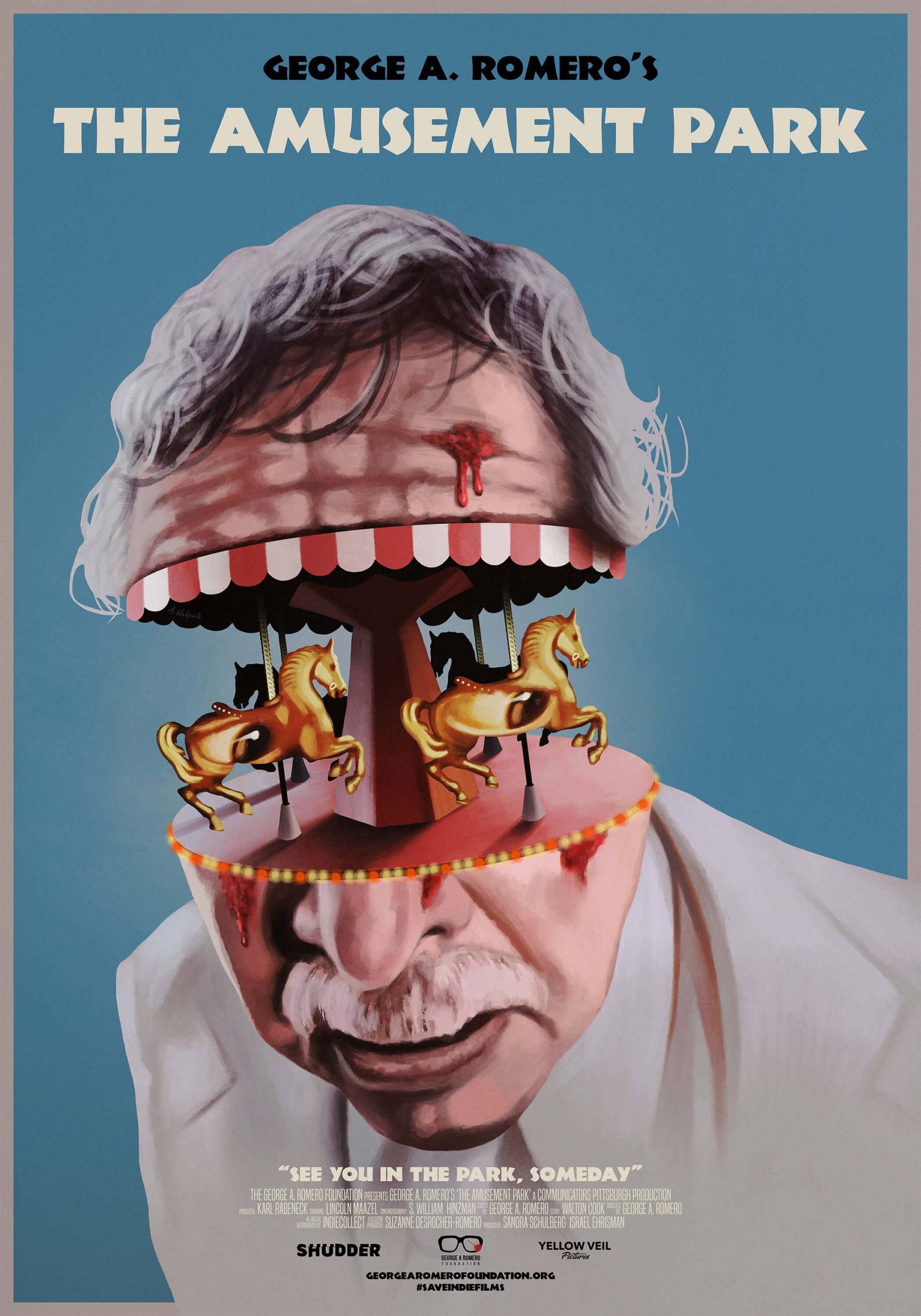

The universal man is played by Lincoln Maazel, a jocular, gentle presence with a wide, naive smile, eyes full of hopeful expectation, and thinning hair and a well-groomed mustache as snowy white as his suit, shirt, tie, and shoes. None of it remains intact long as he enters the amusement park and is indeed beset by one indignity after another: ageism, ableism, exploitation, and general indifference. He is laughed at, pushed around, beat up, and stalked by death in the form of a parkgoer wearing a Halloween mask and carrying a scythe. His hope is extinguished as he experiences the reality of being elderly — and as he sees the thousand-yard stares of other old people at the park left to themselves, shunned, and treated as nuisances that ruin the suspension of reality that comes with entering the park. By the end, the universal man is bloodied, bruised, and dirty, huffing and puffing and clutching a cane in a white room as he grapples with what he just experienced.

The film is a brutal 54 minutes, but it’s not like we’re not warned. Another oddity is that The Amusement Park opens with a four-minute introduction, narrated by Maazel as he wanders Westview Amusement Park, outside Pittsburgh, where most of the film was shot (on an even leaner budget than Dead, at $34,320, and with the help of dozens of volunteers, old and young). It’s an introduction that makes Maazel an Orson Welles-like figure, in a red turtleneck and brown overcoat, preparing us for a journey into a nation where we will all become citizens someday. But it’s also an explicit statement from Romero. As Maazel rattles off the challenges of being old in America, Romero forces us to confront how we encounter and engage with our elderly family members and neighbors. When the film finally begins, we’re made witnesses to those degradations — and because we’re unable to help or put a stop to things, we become complicit in the physical and emotional savagery.

The cinematic amusement park has always been the site of horror and torment: the seedy 1947 adaptation of William Lindsay Gresham’s novel Nightmare Alley; the abandoned funhouse climax of Welles’ 1947 film Lady from Shanghai; the lusty sideshow meet-cute in the 1950 noir classic Gun Crazy; the psychosexual carousel scene in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1951 film Strangers on a Train; the titular Carnival of Souls in Herk Harvey’s 1962 proto-Dead classic. This legacy hangs like a popcorn-and-fries-scented mist over The Amusement Park, and Romero goes full tilt on the expectations it brings to watching his film. When the universal man enters the park, we’re already coiled tight — thanks to the prologue and the opening scene of a clean and bouncy Maazel confronting the beaten down version in the white room, but also because we know to expect bad stuff here. And bad stuff is what we get: barkers swindling old people pawning heirlooms for food and ride tickets, young doctors urging old parkgoers to enter a fun house that’s really a nursing home, a refreshment stand where a rich man gets white-glove treatment and lobster dinner while Maazel is treated like a pariah forced to eat white bread and baked beans, a biker gang who jumps and robs the universal man.

But what Romero also does is push the amusement park nightmare into more dreadful territory. There is the universal existential fear of death throughout, but even more potent is the American terror of aging — especially if that means getting old alone and impoverished in a society that fetishizes rugged individualism and Ayn Randian self-reliance. I’ve seen a lot of movies, but I’ve never experienced a scene as damning and devastating one midway through The Amusement Park, where a fortune teller gives a young couple a glimpse of their future as old people literally left for dead by slumlords and profiteering health care workers. Romero cuts between the old man, writing in pain on a soiled bed; the old wife, terrified her husband is dying, hobbling up and down her building’s crumbling steps to get to a pay phone to call her can’t-be-bothered doctor; a a marching band parading down the street; the young couple’s faces contorting in disbelief and fear; the grinning fortune teller waving her hand over a crystal ball. It’s a master class in social horror. And when the old woman is left begging for a dime to make another call as her husband dies alone in a squalid apartment, it’s the kind of gut-punch punctuation only a master like Romero can land.

It’s unfair to call The Amusement Park a missing link in the Romero filmography, especially since it came so early in his career. It does, though, add contours to his better-known work while anticipating future features. Maazel, for instance, would star in Martin, while the biker gang beating points toward Dawn of the Dead and 1981’s Knightriders. The Amusement Park is also the socially-conscious Romero at his fullest bloom. He always wove concerns into his films — racism in Night of the Living Dead, consumerism in Dawn of the Dead, class in nearly everything — but here he’s unshackled by mass-audience narrative demands. That gives the film an avant-garde, underground vibe, but it’s telling that even as an anthology cataloging the “problems of aging in our society,” it always holds our attention and feels cohesive.

The Amusement Park isn’t Romero’s secret unseen magnum opus, but it is entertaining and important and it’s achingly clear why it never got a real release in 1973. It’s hard to imagine this playing on TV, let alone in a movie theater — it’s too strange, too impressionistic — and while there was a burgeoning independent cinema scene in Pittsburgh back then, it didn’t have the support of what Romero would have had if he were working in New York, for instance.

The biggest impediment, though, was likely its subject matter. When The Amusement Park was completed in 1973, Nixon was staring down Watergate and shoveling coal into the conservative economic engine that would starve social services for the poor and the old and chew up the infrastructure of the New Deal and the Great Society. Tackling those issues head on would have likely limited Romero’s audience, even if the film would have undoubtedly been impactful and done some good.

But nearly five decades later, amid a global pandemic that has made it impossible to ignore the eviscerated social safety net, exacerbated worsening income and class gaps, and has disproportionately impacted our elderly population, The Amusement Park is more powerful than Romero could have anticipated. And it’s time has finally come.