Review of My Perfect Life, by Lynda Barry

Review by Michael Quinn

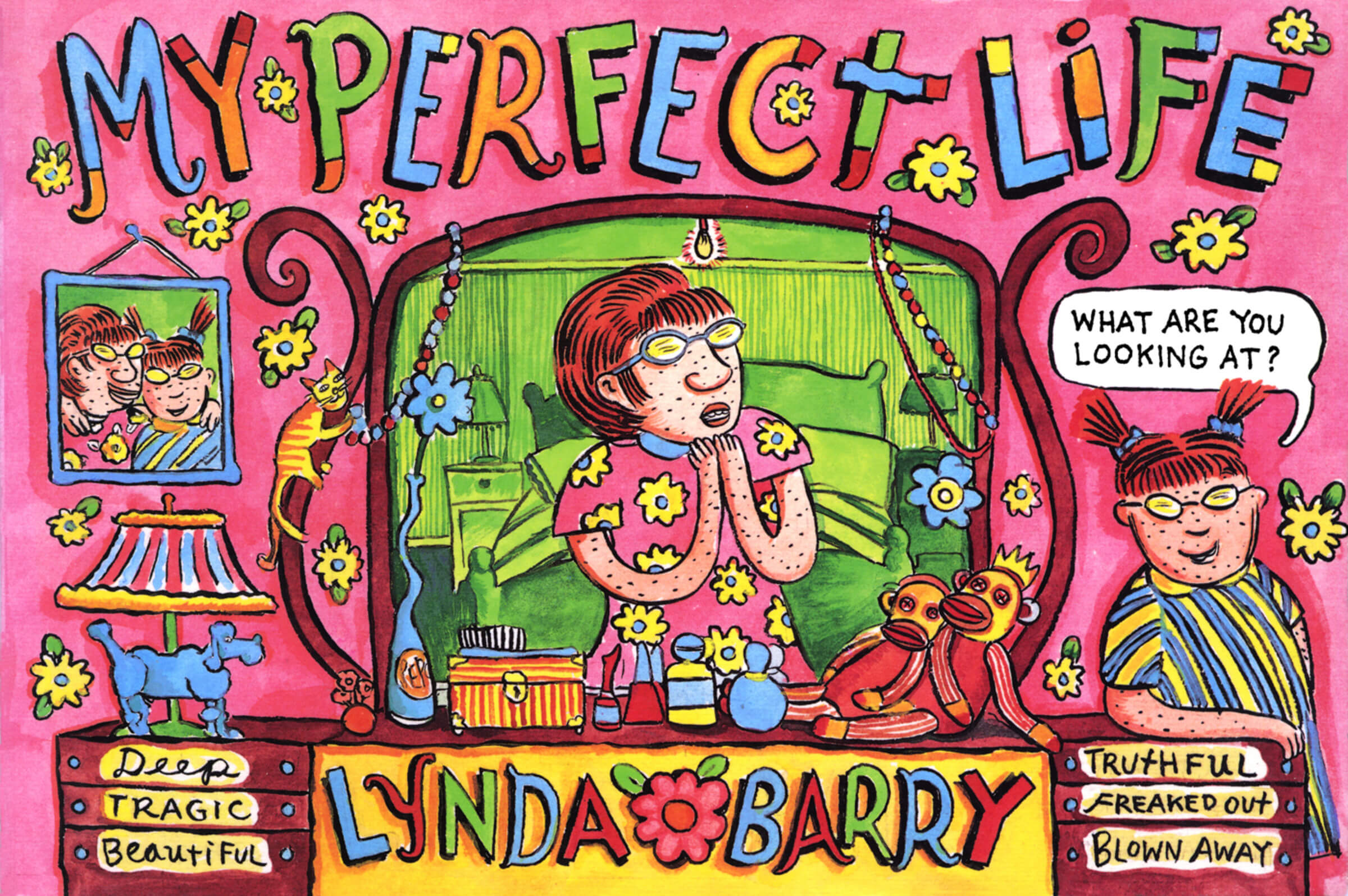

In the `90s, when I was in college, a friend showed me a book from her women’s studies course. She thought I might like it. It was a comic book with a bright pink cover with a drawing of a homely-looking girl standing in front of a mirror. As I flipped through it, I was struck by how messy the drawings were. The story was messy too. It was about an awkward and unpopular teenage girl; the trials she faces at home and at school; and the resilience she finds, finally, by being and accepting herself. I didn’t just like it—I became obsessed with it.

Long out of print, Lynda Barry’s My Perfect Life has just been rereleased by cool Canadian publisher Drawn & Quarterly to blow the minds of a new generation. Barry, a recent Macarthur Fellow (aka the Genius Grant), has proved herself to be a tireless advocate for the transformative power of creativity. She believes anyone can write and illustrate a story. It’s not about talent; it’s about getting out of the way to let the story and images come through you.

This story, unfolding in a series of black and white comic strips, follows fourteen-year-old Maybonne Mullen over the course of a school year. The scribbled drawings seem cinematic, with wide shots and close-ups—sometimes a face fills two of the four frames—that masterfully convey a teenager’s public and private selves: the way we’re perceived and the way we see ourselves. Of course, there are commonalities between the two. This is only one of the things that Maybonne will discover.

At the book’s start, getting settled in a new town, Maybonne writes a note to her best friend Brenda back home filled with the usual gripes: awful teachers, bad lunches, having to share a locker with the new girl at school. “Sometimes I wonder: Is there a curse on my life?” she asks.

Maybonne doesn’t breathe a word of what her home life is like. She shares a bed with her little sister Marlys at their grandmother’s house. First their dad left their mom and then their mom left them. When Maybonne suggests wanting to see her mother at Christmas, her grandmother lets out a snort: “You think she wants to see you?”

When Maybonne looks in the mirror, she sometimes takes off her glasses to squint at her reflection. Even then she hates what she sees. She thinks, “I look at the people at my school. I say, if this was a movie, who would be the star?” One thing she’s sure of: It isn’t her.

Maybonne’s a target for bullies (a group of girls calls her a “lesbo”) and predatory males (she hooks up with a guy named Doug to change this unfair reputation, regrets it, then tries to justify it by convincing herself she’s in love with him). Watching the more-experienced Cindy finger a necklace a boy gave her with a world-weary smile, Maybonne observes, “Before that, Cindy always seemed my same age. Now I see how many spaces she had skipped.”

When a genuinely nice guy takes an interest in Maybonne, she’s horrified to admit she finds him boring: “Brenda told me one time that this thing happens when guys are nice. When guys are nice, your feelings can just sort of stop.”

It’s to God that Maybonne turns for her most serious concerns, although he “might not be the same God as the God of the church,” she explains. She worries about war, pollution, starvation, prejudice, overpopulation, and “why guys quit liking you when you start liking them.”

Like many teenagers, Maybonne has her mood swings. Sometimes she inexplicably feels giddy: watching a sprinkler shoot to life on a summer lawn, running barefoot across the driveway in her nightgown to gossip with Cindy about boys. Other times she feels suicidal, lying awake in her bed at night watching Marlys sleep and imagining how awful it would be for her sister to wake up and find her dead.

Marlys, a little spitfire with two pigtails sprouting from her head like brooms, is an eternal optimist. She’s forever trying to cheer up Maybonne with made-up dances and corny jokes. Failing to get the big reaction she hopes for, Marlys knows her sister well-enough not to take it personally. “Are you riding on another bummer again?” she asks.

Eventually, Maybonne finds ways to self-soothe, like cuddling with an animal. (“The smell of a dog has always made me feel better,” she explains.) At the start of a new school year, she feels gratitude for all of her experiences, good and bad. She’s begun to understand who she is and what she needs—and self-awareness is truly the key to self-acceptance. “Crud is the most normal feeling,” Maybonne says. “They should write that in the sky so people will know and not feel so bad.” I remember reading those words all those years ago and being struck by their truthfulness. My Perfect Life has only gotten better with age.