Todd Field’s Tár begins, essentially, with the end credits: dozens of names in white scrolling over a black background. It could be taken as an indication that it’s time to go home.

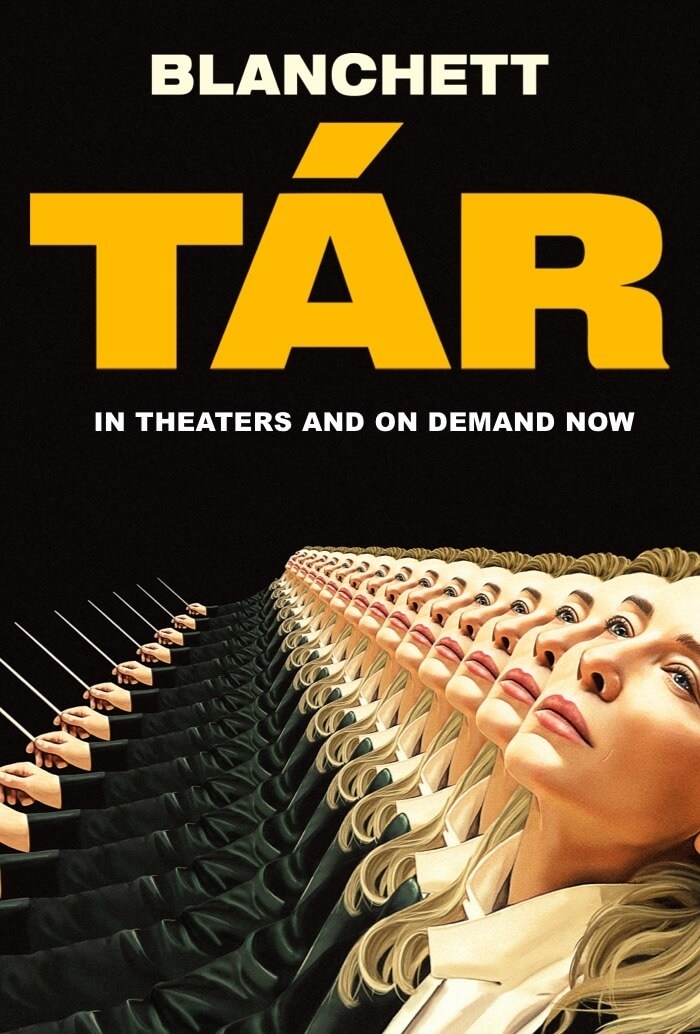

Once the credits are done, things don’t pick up. The first third of the movie is belligerent in its boringness. It sets up the titular, successful orchestra conductor (well played by Cate Blanchett) by showing her onstage with real-world New Yorker contributor Adam Gopnik. Then, a guest lecture at Juilliard finds Tár confronting a male-presenting student who identifies himself as BIPOC about not liking Bach. He doesn’t consider 500-year-old music relevant to today’s world and she tears him up for his narrow vision, to the point where he gathers his stuff and storms out of the lecture hall. After which, she continues to badmouth him in front of the other students. There’s plenty of conversations about Bach and Beethoven, Gustav and Alma Mahler, living composer Anna Thorvaldsdottir and conductor Marin Alsop to show that Tár (and thus writer/producer/director Todd Field) knows her (thus his) stuff. Audience members who don’t know that stuff are left in the dark. Meanwhile, nothing happens to establish or move any sort of story. They just talk.

When things do finally start to move, it’s a downhill run. Tár gets caught up in accusations of sexual harassment of female students. It’s unclear whether or not she did it, but the narrative seems to suggest that while she enjoyed the attention of cute, young students, she didn’t act on their making themselves available. It doesn’t matter if anything more happened between her and her students, though. The point of the story is that she’s an innocent victim of current, and ever shifting, morés.

To put a finer point on it, it’s a story about how cancel culture (the student in the lecture hall) and #metoo (the harassment allegations) can unfairly take down the powerful. Had Tár been male (rather than just wearing expensive and well-tailored men’s suits), this would have been more evident. But Field goes for the counterintuitive, which is what makes the movie so duplicitous. It’s not about a strong woman, it’s about the tyranny of the young. The last words in the movie (coming from a film for which Tár is conducting a live score) are “you will not be judged.” But Tár was judged, leading to her downfall and the movie’s misguided moral message.

The downhill slide continued after the movie had ended, as I ruminated over why it bothered me so much and then engaged in social media about it. (This essay, in fact, as in no small part a rewrite of an extended online diatribe).

Politics aside, the movie is just problematic in its artfulness. Tár jumps back and forth between Manhattan and Berlin (and we do with her, since every scene is about her) without so much as an exterior shot of an airplane to clue us in. Once her career is wrecked, she can apparently only find work in an unnamed, impoverished Southeast Asian country. A guide makes a reference to when Brando was there. Does that mean it’s Vietnam, where Apocalypse Now was set? Or the Philippines, where it was actually shot? That doesn’t seem to matter. Her humiliation is riding public transportation in a country that’s very non-Western.

At one point, early in Tár’s breakdown, she marches around her apartment with an accordion, loudly improvising a song about the apartment next door being for sale. The song is only a few lines long, but apart from watching Sophie Kauer as one of the young infatuations play cello (she studied at the Royal Academy of Music in London for 7 years, starting when she was 10), it’s the only enjoyable scene in the film. The 2021 documentary on Marin Alsop, entitled simply The Conductor, is available on streaming services. It’s far better and about half as long.