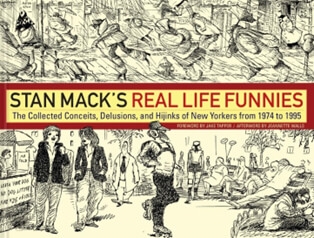

Stan Mack is one of the most prolific story tellers of the 20th century. He’s told over 1,500 tales using thick white paper, a pen and black ink to create comic strips about ordinary people, sometimes in extraordinary locations. A thousand were published in the Village Voice every week for two decades. Now 275 of the best of those will be available come mid-June in a new book, Stan Mack’s Real Life Funnies.

Mack rolled into New York at the dawn of JFK’s New Frontier, toting a degree from the Rhode Island School of Design and a bunch of pens. After becoming art director at the Herald Tribune, rubbing shoulders with notable proponents of an emerging “new journalism” (Breslin, Wolfe, Steinem), he moved on to the New York Times.

A few years later, accompanying Style reporter Georgia Dullea on some of her forays into “Nouvelle Society,” he began jotting down quotes along with his sketches. Georgia was encouraging and eventually a thought bubble popped over Stan’s head: “What if I combine my illustrations with what ordinary people are actually saying?” He pitched the legendary graphic designer, Milton Glaser, at the Village Voice then, on the idea and the strip was born.

If you ever wondered what life was like in New York during its decline and rebirth, look no further. Sure, historians will note the sexual revolution of the 1970s and some have even written books about it, but only Mack will show you what it was like to hang out with the never-busy lifeguard at the Plato’s Retreat pool, given how it’s you know, impossible to have sex while swimming, ergo the swingers never ventured beyond the shallow end. In addition to Pink Pussycat sex shops, Stan’s strips also took us into Bloomingdale’s, squatter apartments, UFO Club meetings, Broadway casting calls, music video shoots, AIDS’ sufferers bedrooms, a King Kong balloon on the Empire state Building, singles bars, a satirist dressed as a padre pedaling a bike with a portable confessional in tow, as well as dreamers, a Don Quixote MD, hustlers and so many other common people, who God must surely have loved, Abe Lincoln liked to point out, because he made so many of them. What follows is a recent conversation we had with Stan, editing out the boring bits.

JE: Stan, when you graduated the Rhode Island School of Design, what did you want to do?

SM: I knew I liked to draw. I liked to draw people. But I wasn’t a serious painter, wasn’t going to paint seascapes on Cape Cod so I headed to New York and took my chances.

JE: Did you have any leads when you got here?

SM: My uncle Freddie knew somebody, and somebody else knew somebody, and all of them went nowhere. So I started with menial art jobs. Maybe it would have been better if I’d grown up in Brooklyn where, as you know, I was born. But we moved to Providence when I was a little kid.

JE: Well, you landed the art director gig at the Herald Tribune and then moved over to the Times. How did you hook up with the Village Voice?

SM: I did a lot of illustrations for New York Magazine, which Clay Felker and Milton Glazer ran, so I knew them before they took over the Village Voice. I was a freelance illustrator, waiting for the phone to ring, which it did, luckily. But I thought if I could somehow create a combination package of drawing and reporting, then I wouldn’t have to wait for that phone call. So I went to Milton. He was the graphics genius who created a whole new look for the Village Voice. I said, what if I go about town and do a piece listening to people, talking with them, sketching the locations. I didn’t know that Milton had created a page he called Urban Comics, and now he was looking to fill it. And after I pitched my idea, he said, “Comics are circulation builders for weeklies. They’re a big deal but you gotta appear regularly. If you could do this thing every week, I’d put it on that page.” And that’s how it began.

JE: Did you come up with the name “Real Life Funnies” and that tag, “All dialogue guaranteed verbatim”?

SM: No. Milton said, “Whatever you’re gonna do, go do it.” He was a visionary. So I wandered around town, I overheard snippets here and there and delivered it in a comic strip format to the editors, not Milton, who was separate from the editors who put together the paper. “Here you go,” I said, and they said, “What’s this?” I told them what I’d done and they said, “What do you mean it’s true? It’s not real, it’s a comic strip, comic strips are fiction, they always have been.” Or at least as far back as they could remember. I said, “No, no, this is all real. None of the words here are made up, these are all people’s words.” And they said, “Well, this is crazy. Who’s gonna believe that? They’re gonna open the newspaper and see a comic strip and they’re going to assume you made it up.”

JE: Reasonable.

SM: Yeah, so then they said, “How about if we call it Real Life Funnies?” I said alright, Real Life Funnies. Then they said, “And we’re gonna put your name in the front of it because we don’t want the responsibility for people asking us if it’s real or not.” Then one of them said, “You know, even that might not be enough. Let’s put ‘verbatim’ underneath it, to say this is absolutely people’s words.” As it turned out, the word verbatim captured readers’ imagination. It’s a nice lively punchy word and it became very much attached to the whole idea of Real Life Funnies.

JE: That’s a fascinating origin story.

SM: Since these were word balloons, I might have to cut a word or two to fit the space-as long as I felt it didn’t change the meaning. but that was as far as I ever went. People’s words were holy.

JE: Did you use a tape recorder?

SM: No. I started with a couple of little pads and two ballpoint pens for backup. I needed a way to carry them that was easy to get at. In those days men didn’t carry bags, there weren’t even belly bags. So I bought a grenade bag at an Army & Navy store, which I could wear on my belt, perfect for my pads and pens.

JE: Perfect for an ex-GI! I saw your video on C-SPAN and you were drawing with what looked to me like just a traditional fountain pen.

SM: It wasn’t a fountain pen, it was a dip pen. It was a little black thing with a metal point which you bought separately. it was crude in a way but also brilliantly sophisticated. Think about Edward Gorey’s drawings [Gorey did the cartoon for PBS’s Masterpiece Mystery]. I went to the Gorey museum on Cape Cod where they displayed some of his tools. Same pens I used. For me, there was something special about the metal point on paper. I’d dip my pen into India ink and the line lasted as long as the ink in the pen point did, and then you had to dip it again, over and over, which is probably why my arm hurts so much now.

JE: Did you carry around the ink?

SM: The ink bottle sat next to my drawing board. And since I was left-handed, I had a tube of white paint to paint over my mistakes because I kept smudging the black ink which was still wet, because I was always in such a mad rush to deliver the drawing to the Voice. It was always last minute. I don’t know how to work except on deadline. I used to think of it as a pizza that I was delivering while it was still hot.

JE: How big were the strips you drew?

SM: 14 by 17 inches. That’s why I thought of it as a pizza, it was the same size as the box.

JE: How would you put the strip together?

SM: At first it was like I collected all the words in a dump truck, backed up to the drawing paper, and dumped ‘em. And whichever ones survived was the strip for that week. After a while I began to look for a story with some sort of beginning, middle, and ending. I had a lot of newspaper background at that point. I knew I needed a lede, a first panel that would tell the reader where they were, which was someplace different every week. I’d often draw a funny little guy with a square nose and mustache, the only ongoing character, he was an onlooker whom the reader could identify with. Basically it was me as a cartoon character.

JE: Did you ever follow a politician around?

SM: I covered three national conventions. Some strips from them are in the book. I’ve been complimented on my caricatures of say, Jimmy Carter. But I’m not a traditional editorial cartoonist commenting on politics. My strips are about people, essentially a bottom-up history. I remember a city public hearing where city council members were meeting to put forward the motion to vote themselves a raise. I just sat among the people watching the politicians on the stage knock down their morning coffees and bagels and doughnuts. Fat cats talking about how they really needed money and not understanding how many in the audience who made far less could even survive in New York. It was a puzzle to them, but it wasn’t going to stop them from voting their own raise, which they went ahead and did. It was political satire from the cheap seats.

JE: Is there any strip in the book that you would pick if you had to be remembered for just one? Or a Top 10 maybe?

SM: No, but there are some which are for me at least great stories and I like them for that reason because they’re more than just that one week. These are strips that have affected the people in them and me, sometimes over the years. Then again, some weeks I’d have a tough time finding any story. I’d have to go to two or three places looking for a story.

JE: So tell me about the UFO group.

SM: In terms of my kind of humor, some strips were easy, like hanging out with believers in visitors from outer space who had great truths to pass on to earthlings. There were pictures of a UFO that might have been peanut butter on the camera lens. As I was leaving, I heard one attendee say to another, “You know. it’s not your usual bunch of kooks here tonight.” And the other said, “These guys are talking the truth.”

JE: Talking about the process of how you actually worked, it seems you were out there with a pen looking for an interesting story you could report.

SM: I was learning as I went. Today they teach visual journalism in art school. Eventually I got a press pass from the Voice that would allow me to go on the floor of a national convention. But even then I was kind of faking it because there were legitimate reporters seriously interviewing important politicians. I was looking for an angle and sometimes that angle was the press themselves, a notoriously thin-skinned bunch.

JE: Well, I guess you could say in some ways you were after the human interest story, the kind they would run for big events, like a delegate from Queens at her first convention.

SM: I remember I was outside the 1992 Democratic Convention in midtown doing a story on the crazies on the periphery when this guy pedals up on his bike towing a portable confessional for delegates to go to Confession.

JE: Joey Skaggs, the satirist! Porto-Fess he called it!

SM: Yeah, exactly. You nailed it: I was doing human interest sidebars – getting stories from people who weren’t important enough to be inside Madison Square Garden.

JE: Did you get along with Jules Feiffer, the Voice’s senior cartoonist?

SM: I knew Feiffer slightly. He didn’t go into the office regularly. I didn’t either. Feiffer was an essential part of the Village Voice just like the logo itself. He was unique and his voice was amazing. I started what you might call the second wave of cartoon strips. Mark Stamaty followed me and then there were some others. Ben Katchor briefly. In my mind Feiffer’s voice was absolutely true, but he was talking about a segment of society he knew very well, a little bit older than me. Mine ranged across such a wide variety of backgrounds and peoples that it really became something different, and it was also more a documentary. Feiffer’s voice, which so captured the people he was writing about and had such perfect pitch, was still coming out of his head. None of my stuff was, except for choosing the place, like the UFO fanatics, Plato’s Retreat, or you name it, that was where my editorial instinct kicked in. But once there, it was those people providing the story.

JE: What did you think of R. Crumb and his ilk?

SM: I was fascinated by them, like the Beatles, like Bob Dylan, like a lot of the illustrator cartoonists I knew of in the ’60s who were overturning the values of the ’50s and setting new pathways. We were all going through a revolution of one kind or another in the ’60s and the idea that Crumb took the comics of my childhood and riffed on them from the underground with the attitudes of the revolution was wonderful. But I was already ensconced in New York as an art director and illustrator, so I was more mainstream—I’d even been in the army. Still, my approach was really off-beat.

Stan Mack will be appearing at the 394th meeting of the NY Comics & Picture-story Symposium in the fall. His new book is available for pre-order on Amazon https://bit.ly/3Uc7ylJ

2 Comments

The NY Comics & Picture Book Symposium has been postponed to the Fall.

Pingback: Stan Mack’s Real Life Funnies, New Book - The Art of the Prank