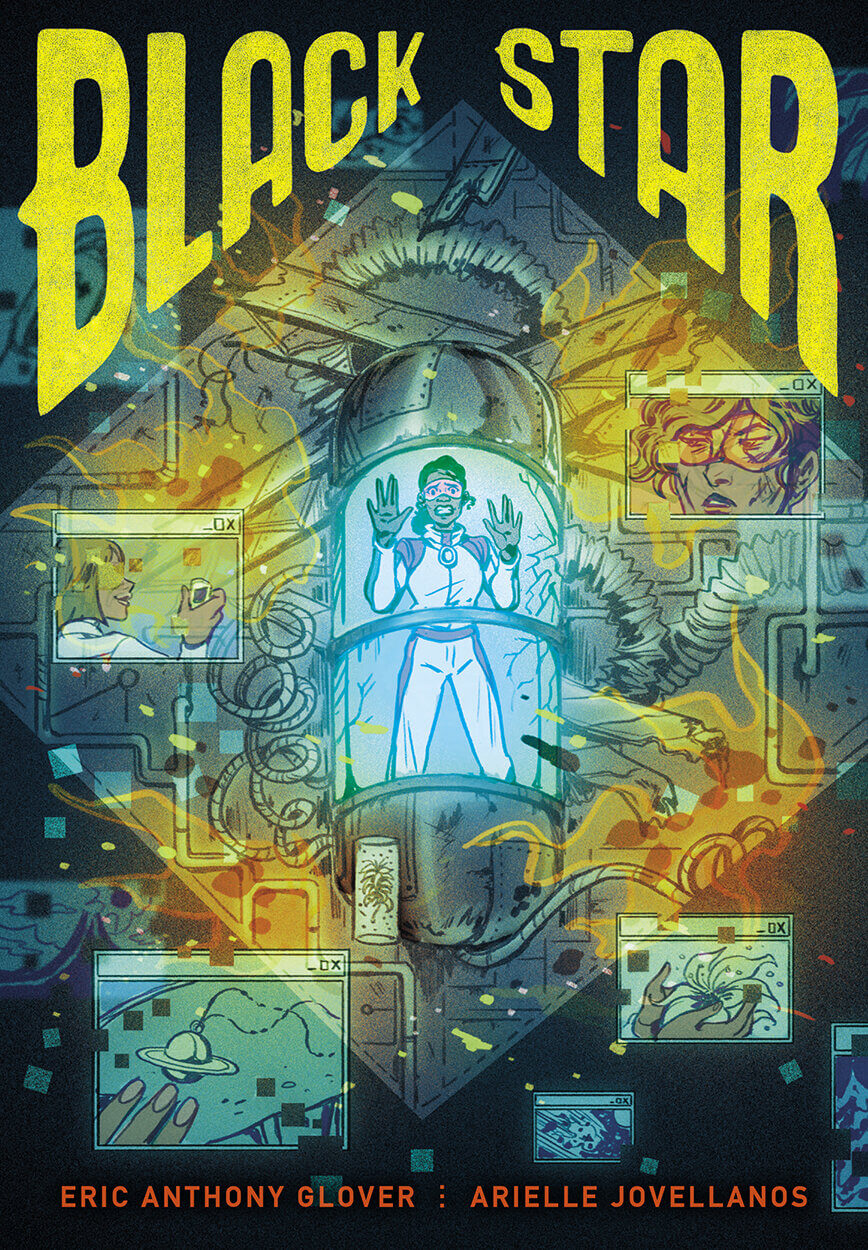

Review of Black Star by Eric Anthony Glover, illustrated by Arielle Jovellanos

Extreme temperatures. Flash flood alerts. Wildfires. Sounds like this past summer, no? These conditions are also found on the fictional planet Eleos, the setting for Eric Anthony Glover’s debut graphic novel, Black Star. Brilliantly illustrated by Arielle Jovellanos, the story follows an all-female team of scientists dispatched on a mission into deep space to retrieve a rare flower needed to generate a vital medicine to save human lives.

The mission hardly qualifies as a success. Caught in an asteroid storm shortly after takeoff, the spaceship crashes on Eleos. Most of the crew is killed on impact. Its two survivors—Dr. Harper North, the leader of the mission, and Samantha Parrish, the team’s wilderness expert—are soon pitted against each other in a game of life-or-death. Battered and bruised, they race each other to the ship’s detached escape shuttle: There’s only room for one of them onboard.

The novel opens with North shortly after the crash and much of the action is seen from her perspective, so it makes sense we’d root for her. But through a series of flashbacks, another picture of her character forms that makes us question our allegiance. Turns out, not so many people died on impact as we initially thought. Trapped in the wreckage, Parrish pleads with North to save the ship’s medic, Fletcher, whom we later learn is her lover. North wastes so time leaving them both behind. Freeing herself, Parrish cradles Fletcher’s lifeless body in her arms after failing to resuccitate her. For Parrish, it’s now no longer simply a question of survival. It’s a matter of revenge.

North, making her way across the inhospitable planet to the escape shuttle, is aided by her tablet, the Guardian—sort of like a super-sophisticated, talking Apple watch. It gives her weather updates, acts as a GPS, and provides detailed information on Parrish’s whereabouts. It’s also able to recall conversations, and provide scenes from the past in which North is able to zoom in on details she might have missed while they were happening—for example, Parrish and Fletcher playing footsie under the table. The Guardian is neutral, yet benevolent, vested in the survival of all of the crew members. North, we realize, is subtly manipulating it by the information she feeds it and the questions she asks—an unusual twist on the old man-versus-machine angle.

The longer we spend time with North, the more we wonder, Is this the person we want to survive? Parrish is hostile, unlikable, but clearly wronged—and somehow, therefore, in the right. The action becomes unexpectedly nail-biting as the two get closer to their target—and their inevitable confrontation.

Glover is a screenwriter and he’s conceived this work cinematically; in fact, it’s based on an unproduced screenplay. The scenes are vividly brought to life by Jovellanos’ fantastic illustrations. North is depicted as a beautiful person of color; Parrish, as a scowling, short-haired Caucasian. They often appear in a tight palette of reds (for North) and blues (for Parrish). Their fights, fittingly, are purple-hued. Sort of functioning as a DVD special feature, Jovellanos gives a little background on her process at the novel’s end, discussing some of her inspirations (including Ripley from Alien), her process (using depictions of North’s hair as signals “dramatizing how she goes from a reclusive scientist on a mission to someone just desperately trying to survive”), and how she conceived the action and landscape. Not all of the ideas made it to the finished book, but it’s an interesting look at an artist’s process.

Graphic novels, like film, are a visual medium, but films are aided by what actors bring to their roles. While none of Glovers’ characters fall flat, they sometimes come up a little short for a reader. We’re plunged onto the planet and we’re plunged into the characters’ lives without any idea of what brought them here as people. We’re not given too much to go on about what motivates them (other than the broad strokes of survival and revenge) or what makes them unique. They say and do the things you’d expect characters in a space comic book to do. The real novelty here isn’t the characters, though; it’s Glover’s skillful manipulation of how we feel about them. This is not a place many novelists have found a way to go, and that alone makes Black Star’s trip to space worth the ride.

Survival Mission, Review by Michael Quinn

READ OUR FULL PRINT EDITION

Our Sister Publication

a word from our sponsors!

Latest Media Guide!

Where to find the Star-Revue

How many have visited our site?

Social Media

Most Popular

Big donors taking an interest in our City Council races

Wraptor celebrates the start of spring

Related Posts

Special birthday issue – information for advertisers

Author George Fiala George Fiala has worked in radio, newspapers and direct marketing his whole life, except for when he was a vendor at Shea Stadium, pizza and cheesesteak maker in Lancaster, PA, and an occasional comic book dealer. He studied English and drinking in college, international relations at the New School, and in his spare time plays drums and

PS 15’s ACES program a boon for students with special needs, by Laryn Kuchta

At P.S. 15 Patrick F. Daly in Red Hook, staff are reshaping the way elementary schoolers learn educationally and socially. They’ve put special emphasis on programs for students with intellectual disabilities and students who are learning or want to learn a second language, making sure those students have the same advantages and interactions any other child would. P.S. 15’s ACES

Big donors taking an interest in our City Council races

The New York City Council primary is less than three months away, and as campaigns are picking up steam, so are donations. In districts 38 and 39 in South Brooklyn, Incumbents Alexa Avilés (District 38) and Shahana Hanif (District 39) are being challenged by two moderate Democrats, and as we reported last month, big money is making its way into

Wraptor celebrates the start of spring

Red Hook’s Wraptor Restaurant, located at 358 Columbia St., marked the start of spring on March 30. Despite cool weather in the low 50s, more than 50 people showed up to enjoy the festivities. “We wanted to do something nice for everyone and celebrate the start of the spring so we got the permits to have everyone out in front,”