American journalism is on the ropes. The nation has lost one in four newspapers — 2,100 publications — since 2019. (That number has surely grown during the pandemic.) Half of what’s left is owned by vulture capitalists, private equity firms and hedge funds that have perverted local media ownership into cynical resource extraction. Newsrooms are gutted, and what’s left is consolidated for maximum short-term profit. These VC-run specters debase themselves at the altars of algorithms, sullying their communities by chasing cheap clickbait traffic. And that’s if you’re lucky enough to still have a paper. Some 65 million Americans live in news deserts.

How did this happen? How could the shining newsroom on the hill fall into such disrepair? Art Cullen, the nobody’s-fool editor of the Storm Lake Times in Storm Lake, Iowa, has some thoughts.

“Rural communities are a lot weaker now than they used to be, and that makes rural newspapers weaker,” Cullen says in the new documentary Storm Lake. “Without strong local journalism to tell the community’s story, the fabric of the place becomes frayed.”

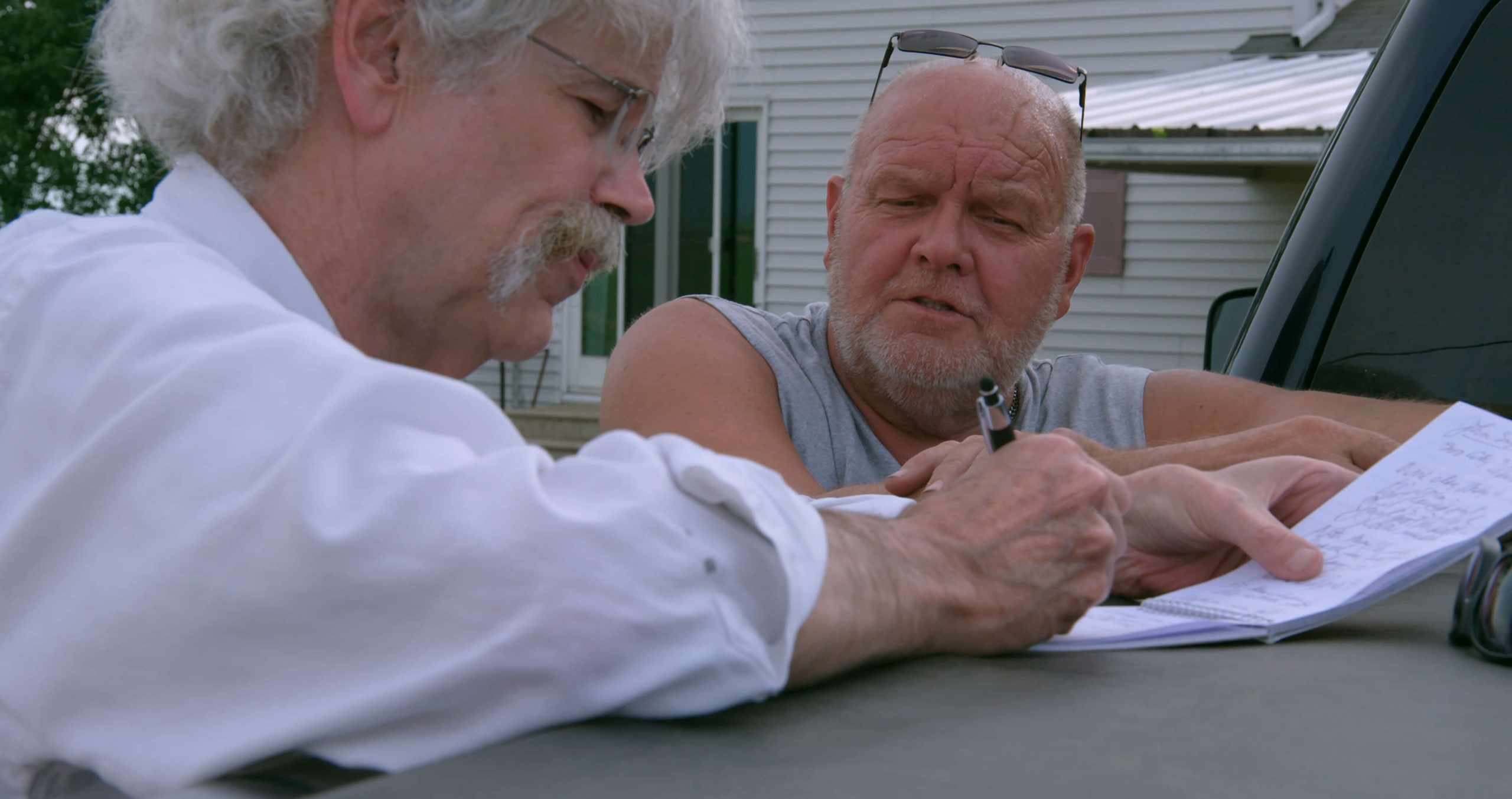

Art and his brother John, the paper’s publisher, founded the Times in 1990, and they’ve seen up close the forces reducing that fabric to shreds: bitterly-divided politics, vertically-integrated conglomerates killing small businesses that form the bedrock of local advertising, social media. “Without readers you’ve got nothing,” Cullen says in the film. “But now people want to get their news for free because apparently looking at their breakfast on Facebook is all the information they need to live as an informed voter in America. That’s not how you sustain a democracy.”

Storm Lake, directed by Beth Levison and Jerry Risius and currently on the festival circuit and playing a limited theatrical run ahead of a premiere on PBS’ Independent Lens on November 15, is about a newspaper and the family that owns it, powers it, and ensures it remains on newsstands. It’s also a documentary about the community that sustains the twice-weekly paper, the neighbors and citizens who make up the readership and whose stories the paper tells. “When it comes to news,” Cullen says in the film, “our motto is, ‘If it didn’t happen in Buena Vista County, it didn’t happen.’”

But perhaps most importantly, Levison and Risius weave those narratives into “a treatise on civic engagement,” as Cullen describes it to the Star-Revue, and the primacy of local media in our national conversation. “That’s the role newspapers fundamentally play, and people take that for granted,” he continues. “I hope people [watching the film] can see the connection between a functioning democracy and an informed electorate.”

That reality, so vital to the American experiment, had been obfuscated by more than a decade of the Facebook and Twitter outrage-hate-read machines. It was further eroded in the wake of Donald Trump’s election in 2016, when fact and truth somehow became up for grabs. Americans’ trust in media cratered during this time, which coincided with an acceleration of shuttering newsrooms. It was also in this environment that the Storm Lake Times and Art Cullen won a 2017 Pulitzer Prize for a series of editorials “that successfully challenged powerful corporate agricultural interests in Iowa.” Suddenly, this little paper in northwest Iowa — and the Mark Twain lookalike at the top of the masthead — gained national attention. Publishers came calling; cable news and internationally read papers, too. “Small Town Paper Makes Good” is a clicky headline when all other news about small town newspapers is calamitous.

Risius, a cinematographer and native Iowan, also came to town. He lives in Brooklyn now but originally hails from Buffalo Center, about an hour from Storm Lake. Like so many others, he noticed Cullen and the Times’ Pulitzer win and, intrigued, paid the paper a visit. Risius, spent half a day with Cullen, shot some material, and soon reached out to Levison — both teach at the School of Visual Arts — about making a feature documentary. Levison was working on another project and couldn’t take it on. A bit later, in August 2018, Risius sent Levison a column Cullen wrote for the New York Times, “In My Iowa Town, We Need Immigrants.”

“It made me cry,” Levison says. “I’ve never really heard a voice like that before. His perspective was fascinating, and I thought, ‘Wow, if these 800 words are so powerful, I wonder if there’s something here.’” She looked at what Risius shot on that half-day scout, she got on board, and soon they began raising money to make the film.

Storm Lake begins in March 2019, taking us inside the Times newsroom as it covers everything from the Democratic presidential primary to climate change’s impact on crop growth to the Iowa Pork Queen’s visit to an elementary school (with a diapered piglet in tow). It also captures the ethic that earned the paper that Pulitzer. Its concluding section chronicles the paper in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic taking to task the state government and Tyson Foods for misinformation and obfuscation about the true toll of the virus — especially on meatpacking plant employees, who are overwhelmingly immigrant and, often, undocumented.

When the filmmakers came to Storm Lake, Levison says “we were really open to what we saw on the ground. We really went with open hearts, open minds, and I think that made a big difference.” The filmmakers encountered some folks who didn’t want to appear in a film about the Storm Lake Times and the Cullens, such was their opposition to the staunchly progressive paper and family. But they otherwise gained wide access to the community and the Cullens.

That includes witnessing up close the daily struggle to keep the Times’ lights on. The Cullens — Art’s son Tom, wife Dolores, and sister-in-law Mary are also on staff as reporters — always seem to be one dropped ad away from disaster. To help keep the enterprise afloat, Art and John are now on Social Security and volunteer their time to ensure the paper continues making payroll. The film is a necessary corrective to the myths that sprung up about the paper in the wake of its Pulitzer win, and the Cullens’ openness and candor is bracing.

“What’s good for the goose is good for the gander. If I can go nose into people’s business, why shouldn’t I have a film crew come in and nose in our business,” Cullen says. “They didn’t make us look like hicks or braggarts or whiners, and they easily could have.”

Levison says that while she and Risius thought they were making a documentary about Art, as they shot they “really started to see how this isn’t just a film about a newspaper. It’s also about a community. Those two are really deeply intertwined and interdependent.” And as the film makes clear, that interdependence is a microcosm of the larger story of the state of American journalism.

Local, fact-based journalism is in danger, imperiling a free and healthy press and a healthy and functioning America. Locally-owned papers like the Storm Lake Times, the Carroll Times Herald, and others in the Western Iowa Journalism Foundation are rightly heralded as success stories in an age of hedge fund dominance. But it’s all too tenuous when a paper’s fate can come down to external factors like a lost advertiser or onerous health insurance premium increases.

That’s the story Risius and Levison capture in Storm Lake. Its call to arms to defend journalism is rousing for those of us who love newspapers, but it’s also a snap-to-reality awakening for others who might not appreciate the precariousness of American journalism’s future. Newspapers continue to close. Vulture capitalists continue gobbling up and hollowing out newsrooms. Facebook and YouTube continue to hold outsized importance as platforms for news consumption. Hope could be on the way in the form of the bipartisan Local Journalism Sustainability Act. If it becomes law, its tax breaks and credits could staunch the bleeding and help resuscitate the industry. But if neglect remains the norm, the American experiment will teeter, dangerously.

One cause for optimism: Levison says the film has been received better than either she or Risius could have predicted. “I never thought we would sell out theatrical screenings or have the kinds of conversations we’ve had,” she adds. “There’s been a lot of demand for the film, and that’s having an impact.”

Another: Cullen says he thinks “people are recognizing the value of good journalism, good, honest reporting, informed opinions, and they’re willing to pay for it.”

“There’s something unique about a newspaper that tries to embrace the whole community and not just one funnel or silo,” he adds. “Weddings and engagements and babies and quarantine news and who got busted for drunk driving — that’s something that brings a community together in ways these silos of information don’t, and that’s worth preserving somehow.”

Storm Lake will screen at the Hamptons International Film Festival on October 13 and premier on PBS’ Independent Lens November 15. Additional screening information can be found online at stormlakemovie.com.