My last in person museum experience was at the MoMa in February. As the months have passed and the pandemic still rages on, I have been eager to engage with new art in an immersive way. UNTITLED’s (a contemporary art fair organizer) inaugural VR art fair, UNTITLED Art Online (running from July 29th through August 9th), looked like a promising way to engage with works outside of the standard static online format of clicking through pages and images.

Longing for even a semblance of the experience of visiting a museum, art institutions are reinventing how to engage with their audiences. Methods range from the Met’s AR experiences allowing users to project ancient sculptures in their homes to the Getty Center using the popular Nintendo Switch game Animal Crossing to showcase work in a new and accessible context. Many art fairs have followed suite and pivoted to new ways to engage their audiences. Virtual tours have emerged as a popular way for fairs to continue showing artists’ works without the need for in person viewing. The new modality has helped fairs achieve a more global reach but simultaneously somewhat reduced the exclusive nature that is inherent with the prior format.

Touting itself as the “first-ever VR fair,” I was interested to see how the virtual edition of UNTITLED would be handled, having physically attended it last year. To recreate the in-person feel of an art fair, a company called Artland was used to allow users to point and click as a way to stroll through the exhibition hall. I opted for navigating the fair through clicking in a browser, though the option of experiencing the fair through VR equipment (a technology which has yet to see widespread adoption, likely meaning not the way most viewers would see the fair) would have surely made the experience more immersive. In addition to the exhibition space, UNTITLED Art Online also included a schedule of virtual programming, from video conversations with curators, gallery representatives, and artists themselves.

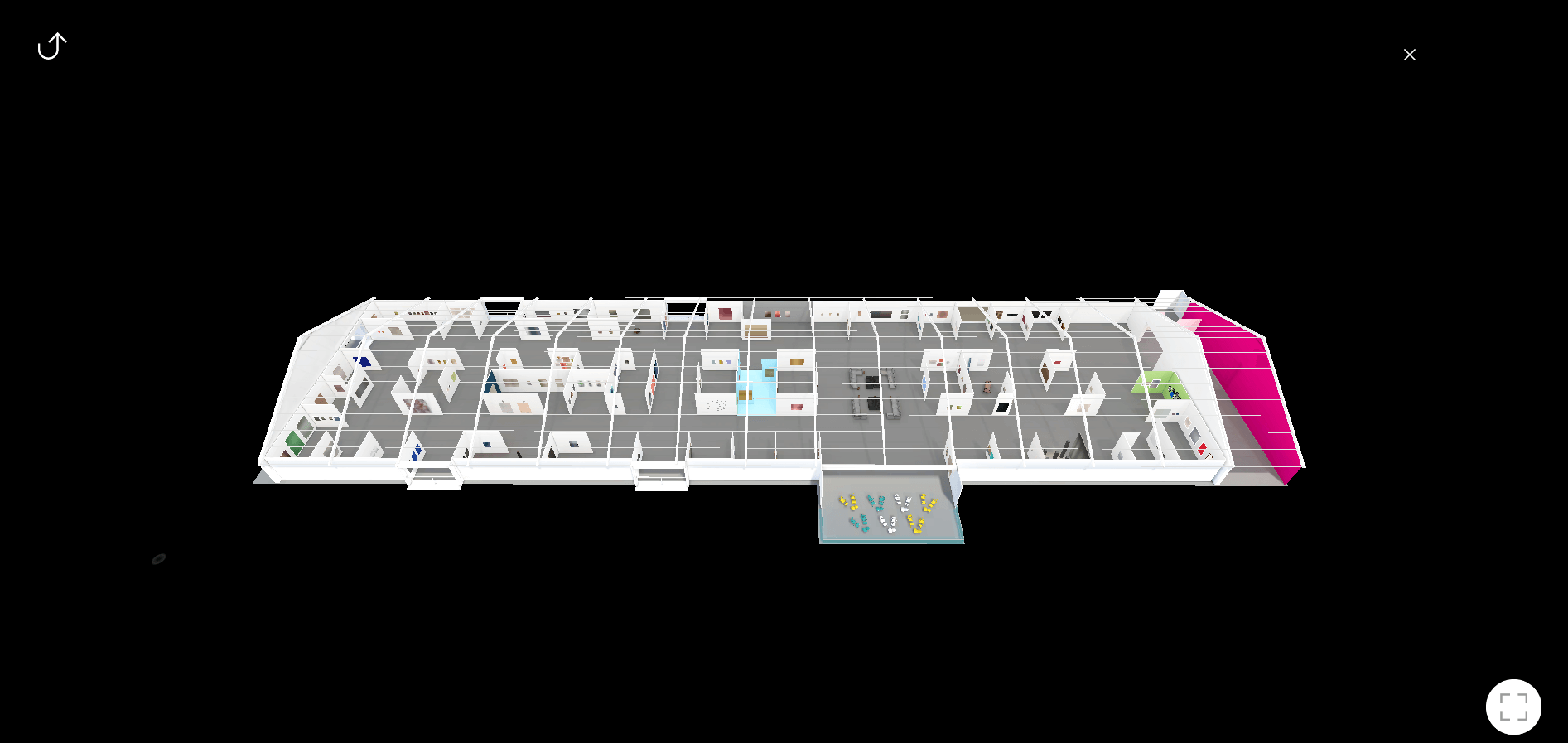

The format succeeded in some ways, such as the fairly easy to navigate video game-like way to traverse the virtual exhibition hall. Users explored the fair through pointing and clicking on where they would like to go, which would then move the view in a somewhat fluid human-like walking pace. For those wishing to quickly navigate to a particular booth, the dollhouse view allowed for getting a birds-eye view of the entire exhibition hall and clicking on the booth one would like to visit and getting transported there instantly.

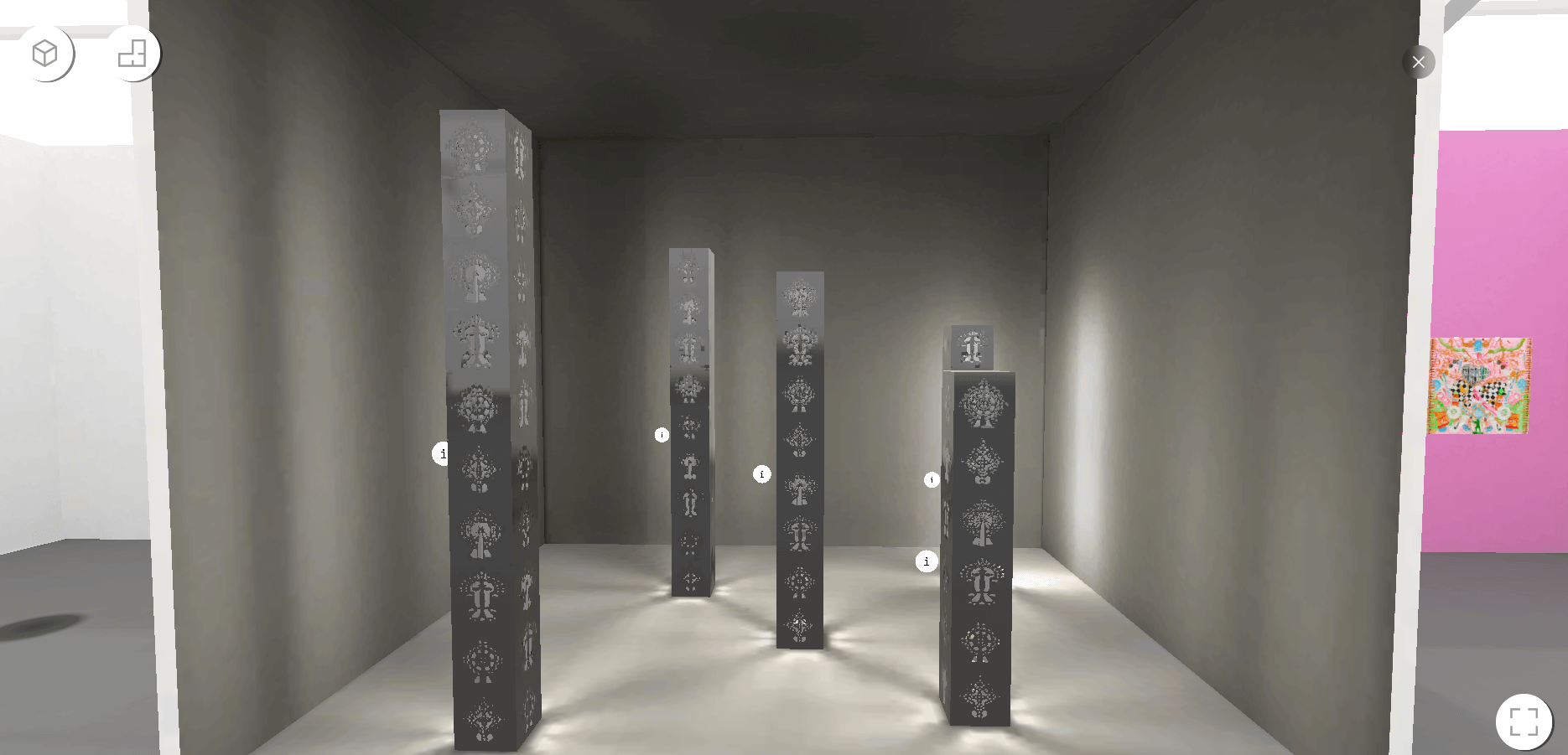

Certain pieces worked especially well in the virtual immersive format, namely Tsedaye Makonnen’s sculptures Senait & Nahom | The Peacemaker & The Comforter (2019), a series of seven engraved mirrored towers illuminated through internal lighting elements. The pieces explore themes related to migration and transnational Black experiences, with each of the individual cubes of the sculptures memorializing the name of a Black woman whose life was cut short due to institutionalized racism. As a powerful and meditative work reminiscent of a candle lit vigil, which is as relevant now as it was in 2019, the sculptures read in a life-like way within the virtual space, allowing the viewer to be immersed in the reflective nature of the pieces.

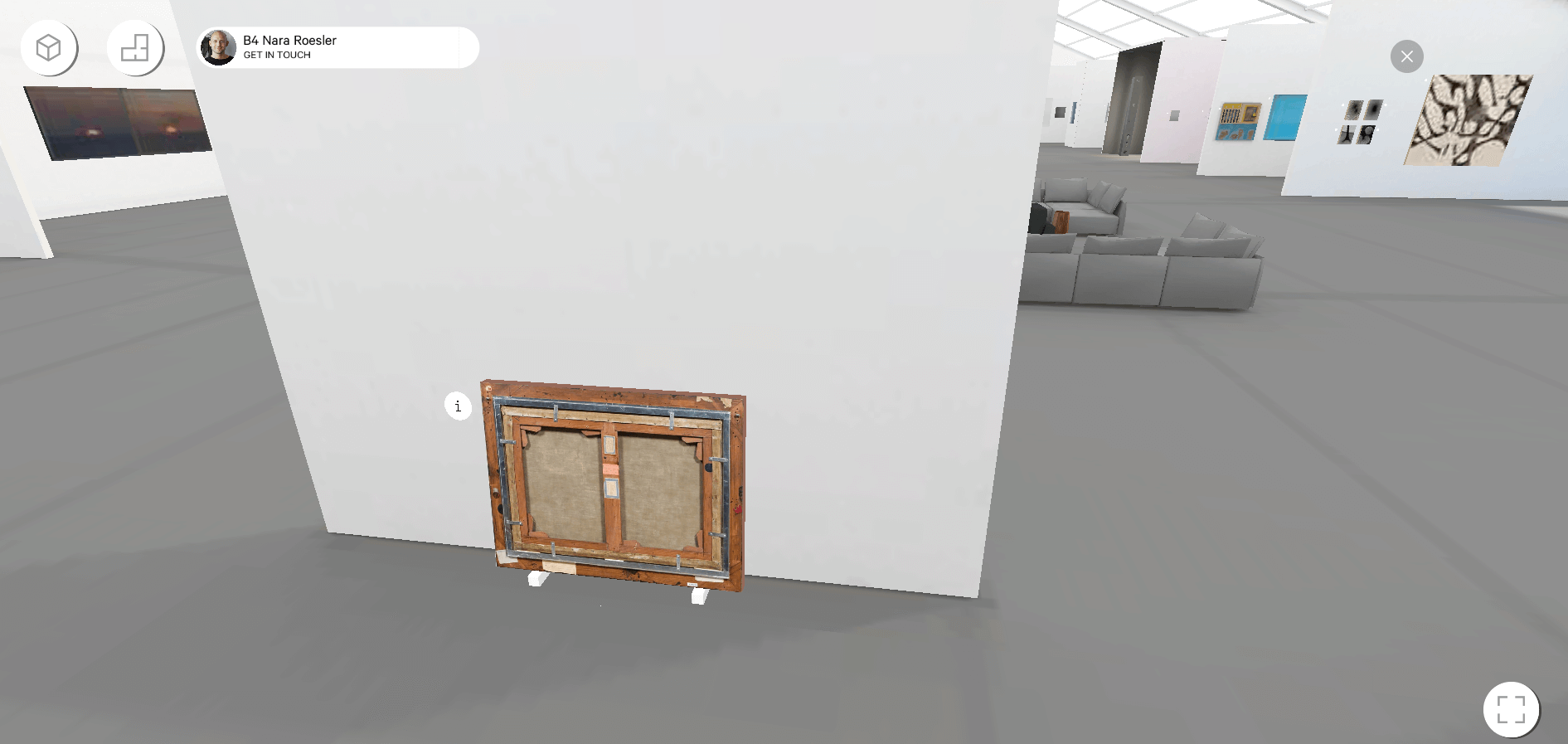

Other works in the fair which deviated from the standard format of canvas on a wall included Vik Muniz’s Verso (Back of the Painting): Ilha de Itamaraca (2016). The art object exists as an interesting study in subverting reality through an extracting detailed recreation of the back of Frans Post’s seventeenth century painting of the same name. In the virtual gallery booth, the painting is displayed on the floor, leaning against the wall in stark contrast to the mainly traditionally displayed paintings around it. This deliberate recreation of the curatorial details for this work helped further the immersive quality of the fair overall.

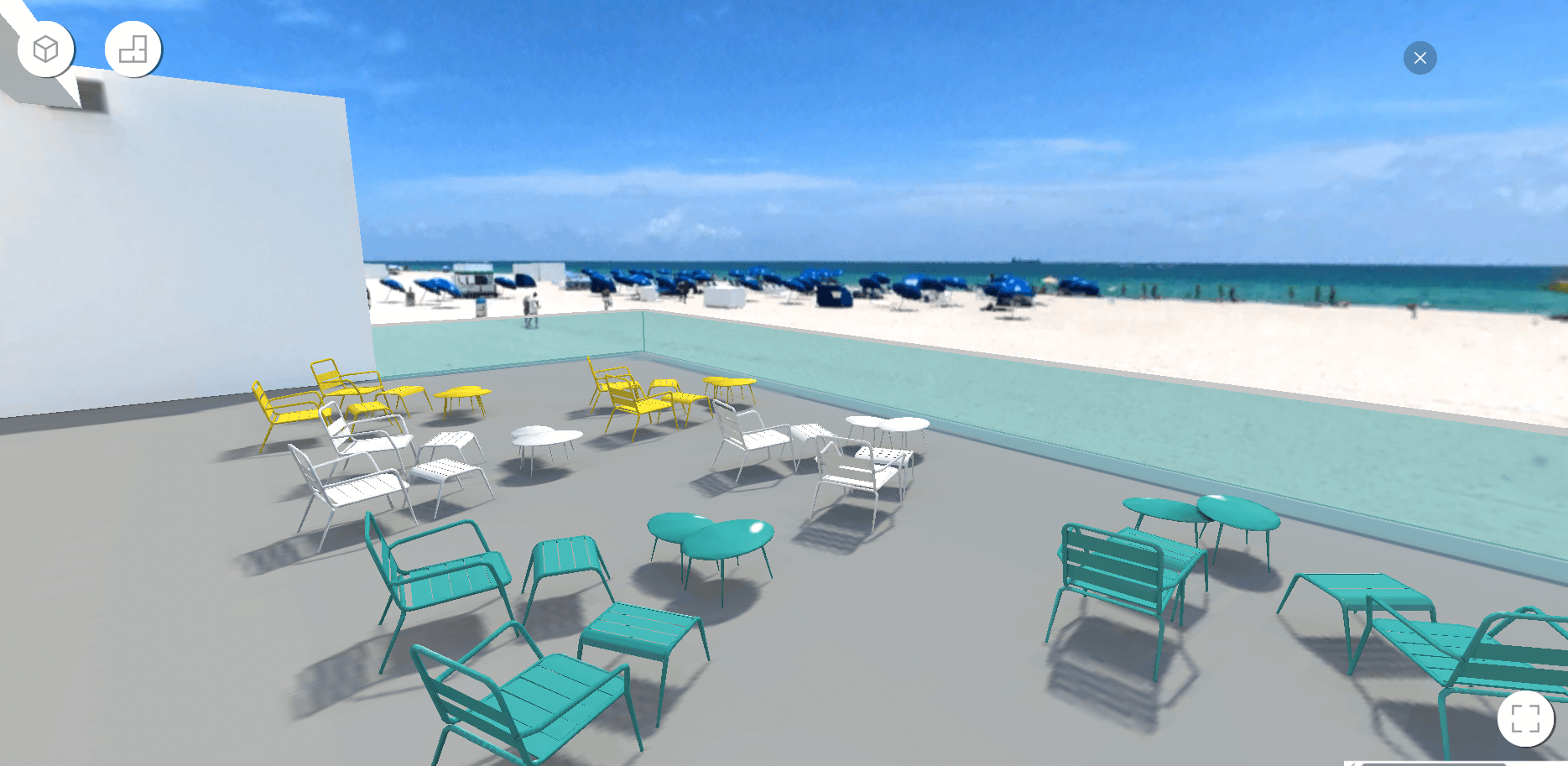

However, UNTITLED Art Online fell short in some respects, especially when the illusion behind the fair was disrupted through issues of scale and other inconsistencies. Areas such as the lounge were not to scale and allowed the visitor to walk atop them like a rampaging giant. Additionally, given the virtual nature of the fair, the exclusion of any multimedia works such as video or virtual works that took advantage of the VR setting (which do exist), was surprising and seemed like a missed opportunity by the galleries. Overall, the format worked well and helped breathe life into touring art fairs and exhibitions online during challenging times but fell flat of truly leveraging the VR itself to create a more unique art fair experience. On a personal note, even though the fair itself wasn’t revolutionary, it did help recreate some sense of normalcy of pre-pandemic life in a virtual setting.

Author

-

Piotr Pillardy is an arts/music writer for the Red Hook Star-Revue. He received a BA in History of Art and History from Cornell University and lives in Brooklyn

View all posts

Piotr Pillardy is an arts/music writer for the Red Hook Star-Revue. He received a BA in History of Art and History from Cornell University and lives in Brooklyn