Among the most powerful recent exhibitions I’ve visited in the city, Shahidul Alam: Truth to Power at the Rubin Museum on West 17th Street chronicles the four-decade career of the prolific Bangladeshi photographer, writer, and activist Shahidul Alam. The first major U.S. museum retrospective of his work, the exhibition features both film and digital photography, Alam’s writing, contact sheets, and other media spanning the artist’s career. Alam, who has been jailed numerous times for his activism, shows Bangladesh and South Asia through impactful photography that seeks to combat the predominant Western categorization of the region as the “Third World” or “Global South.”

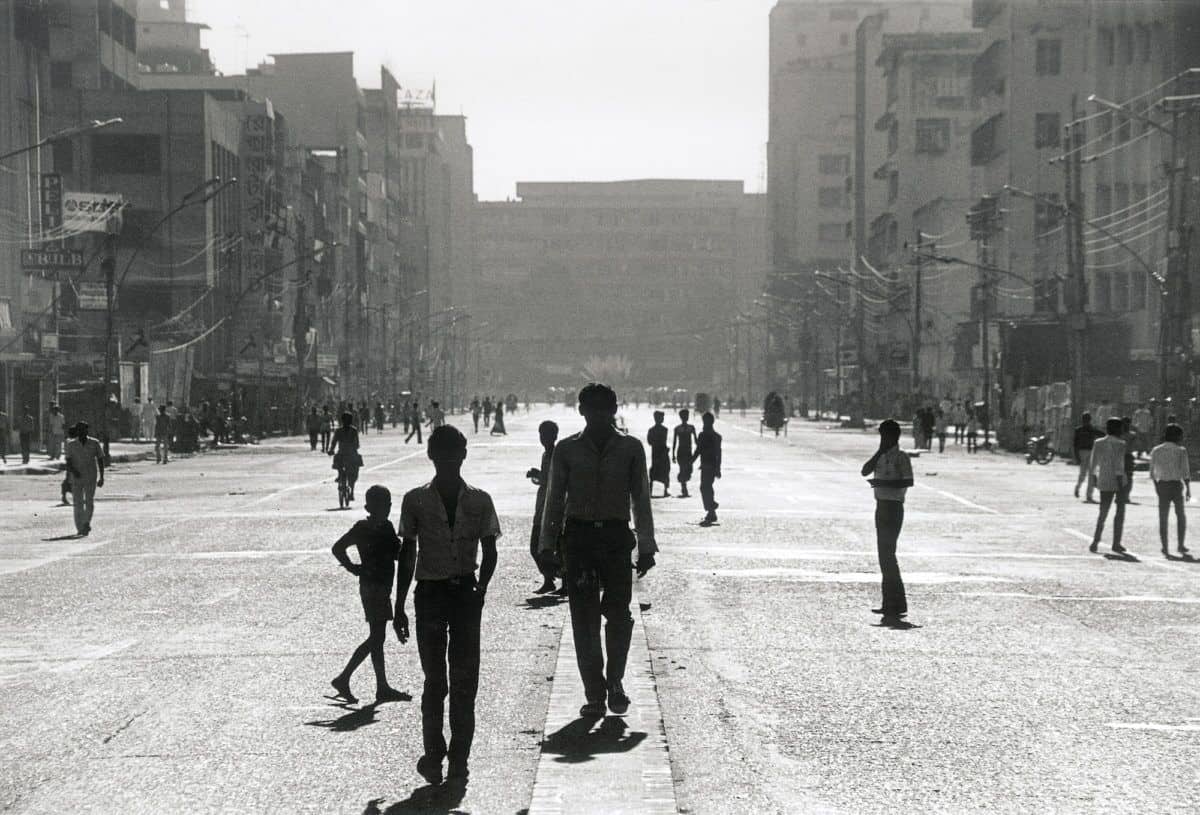

The exhibition starts with Alam’s work exploring Bangladesh’s political situation, especially within the context of the aftermath of the country’s independence from Pakistan in 1971. An example of his earlier work in black and white 35mm film (the medium for the vast majority of the work) from 1987, Protesters in Motijheel Break Section 44 on Dhaka Siege Day documents and frames the protests related the opposition parties uniting to oust President Ershad. The image shows the uncharacteristically empty commercial center of Dhaka, framing figures occupying the street and memorializing the momentous event with an image. This type of street photography and framing brings to mind the work of French photographers Henri Cartier-Bresson and Eugène Atget. However, Alam, through the scenes he chooses to depict, imbues the images with both cultural and political significance outside of a focus on their aesthetic compositions like the Western photographers’ work.

These photographs are quite different than the work of other well-known photographers from the subcontinent, such as Raghubir Singh. Singh’s usually vivid and colorful documentations of daily scenes and landscapes of India, such as New Delhi (1999), are largely apolitical in contrast to Alam’s fiercely and unapologetically politically-charged scenes of protest and dissent.

![]() Another set of images in this section frames Bangladesh in the ‘80s in a particularly powerful way, calling attention to a deep wealth divide in the nation. In Wedding Guests (1988) and Abahani Wedding (1988), Alam documented the opulent wedding of a powerful Bangladeshi minister, which took place as much of the nation was experiencing catastrophic flooding. The curation explores this duality with images to the right of the wedding photographs, including Woman Cooking on Rooftop (1988) and Woman Wading in Flood (1988), which starkly demonstrate this divide. Additionally, a recording of the Adhan, or Islamic call to prayer, emanates from the central museum atrium and acts as a sonic background to the exhibition which brings to mind the role of religion in rallying political favor in the country that is de facto an Islamic nation, though claims secularity in its constitution.

Another set of images in this section frames Bangladesh in the ‘80s in a particularly powerful way, calling attention to a deep wealth divide in the nation. In Wedding Guests (1988) and Abahani Wedding (1988), Alam documented the opulent wedding of a powerful Bangladeshi minister, which took place as much of the nation was experiencing catastrophic flooding. The curation explores this duality with images to the right of the wedding photographs, including Woman Cooking on Rooftop (1988) and Woman Wading in Flood (1988), which starkly demonstrate this divide. Additionally, a recording of the Adhan, or Islamic call to prayer, emanates from the central museum atrium and acts as a sonic background to the exhibition which brings to mind the role of religion in rallying political favor in the country that is de facto an Islamic nation, though claims secularity in its constitution.

Closing off this section of the exhibition was a particularly powerful image entitled Woman in Ballot Booth (1991), which shows a woman voting in a makeshift ballot booth consisting of a translucent veil following the resignation of President Ershad. Next to the image is both the text and a spoken word recording of Alam reading a letter decrying the proliferation of propaganda through state media at this time, even in the wake of the fall of the Ershad regime. In a table in the center of the room, there are contact sheets from the photographer, giving insight into his artistic process and production.

The next part of the show features a section of work Alam created in tribute and as an investigation into Kalpana Chakma, a human rights activist and feminist who has not been seen since her disappearance in June of 1996. This section starts with a selection of color photographs such as Red Orna (2013) that are close up abstract photos of Chakma’s garments and other personal ephemera. This photograph shows a close up depiction of her orna, a shawi-like cloth worn by Muslim women, but thoroughly abstracts the representational source material in stark contrast to the more documentational earlier photography. Other, less abstract works include Sole of Mud-Caked Shoe of Kalpana Chakma (2014), which was taken on the 18th anniversary of the disappearance of the activist.

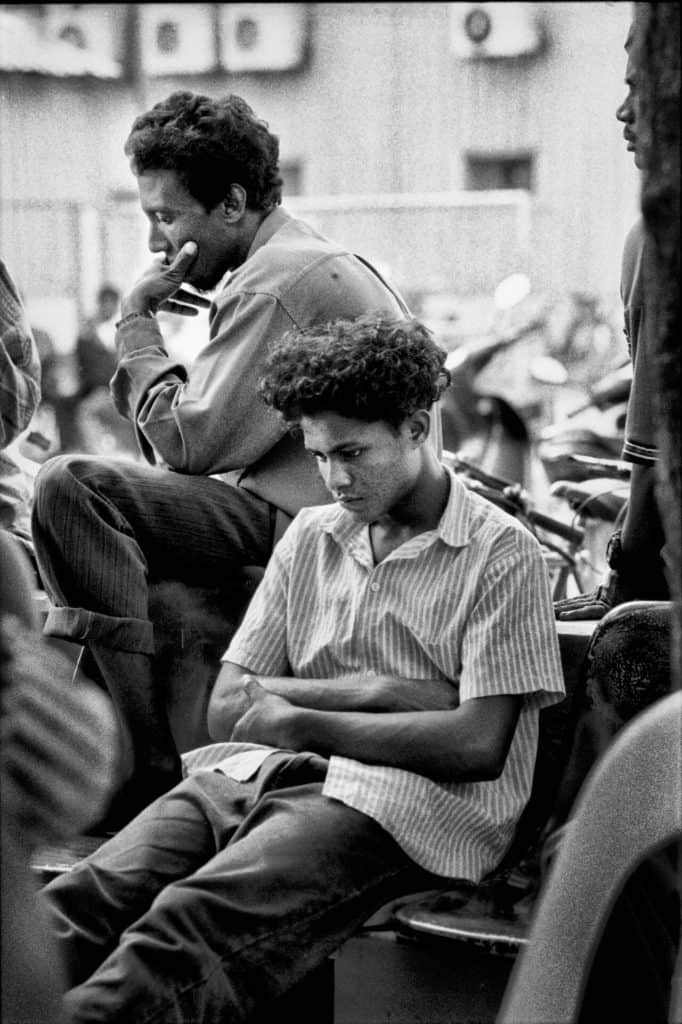

The exhibition continues with a series exploring the role of migrant workers in Bangladeshi society, who often must travel past the nation’s borders to work in order to send money back to their families from places such as Abu Dhabi and the Maldives. A poignant portrait from this series was Bangladeshi Migrant Workers in Maldives (1994), showing workers at the docks in Male, the capital of the Maldives. The photograph thoroughly captures the individual’s sense of tedium resulting from the work, with one man shown almost facing the lens and the other shown in profile. The photograph simultaneously captures the opportunity for a better life that this labor presents and the toll of the labor itself. Another work in this section explores the death of Nurjahan Begum and suggests a tragic narrative among the largely documentational work. The 1993 series of black and white photographs tells the story of Begum, who was abandoned by her husband and wished to remarry but needed to receive the approval of the village imam. The imam originally approved the decision but later revoked it, ultimately resulting in Begum being publicly stoned and later dying by alleged suicide, highlighting the struggles for women’s rights in the country.

The penultimate section of the show features Alam’s newer color photography, which explores topics from refugee resettlement by the ethnic and religious minority Rohingya people from Myanmar. Images such as Densely Packed Homes in Balukhali Camp (2017) and Signaling on River Naf at Nightfall (2017) help shed light on the conditions experienced by the refugees fleeing persecution. Other images in this section explore the effect of the climate crisis on Bangladesh, a nation extremely susceptible to rising sea levels.

In an interesting turn, the exhibition ends with an iPad showing some of Alam’s most recent photographic works shot on an iPhone. These photographs, mostly apolitical depictions of daily life and more in line with the works of Singh, show scenes both from Alam’s life in Dhaka and from his travels abroad. As well framed and composed as Alam’s film photographs, these digital images, such as one showing men and women praying at a mosque in Kuala Lumpur and a beautiful image of changing leaves in Auckland, further point to Alam’s masterful use of the camera. The exhibition will be on view at the Rubin Museum on West 17th Street through May 4, 2020.

Author

-

Piotr Pillardy is an arts/music writer for the Red Hook Star-Revue. He received a BA in History of Art and History from Cornell University and lives in Brooklyn

View all posts

Piotr Pillardy is an arts/music writer for the Red Hook Star-Revue. He received a BA in History of Art and History from Cornell University and lives in Brooklyn

One Comment

Pingback: 'Shahidul Alam: Fact to Energy' on the Rubin Museum - fooshya.com