At the start of Lola Quivoron’s debut feature, Rodeo, a shaky camera follows Julia (Julie Ledru, exceptional in her first film) through a chaotic scene in the cold, echoing halls of a French housing project. Men shout at her, harass her, follow her, try to stop her — all the way outside, where she climbs into a truck and implores the driver to take her away. Only when the rail-thin young woman, dressed masculinely in a baggy t-shirt and shorts and calling everyone bro, promises to calm down and stop insulting these guys (one of whom is her brother) is she allowed to be on her way. When Julia gets to where she’s going, she pretends to be an interested buyer of some bougie suburban dude’s motorbike, convincing him to let her test drive it before gunning the bike and claiming it as hers, throwing the owner a middle finger as she rides off.

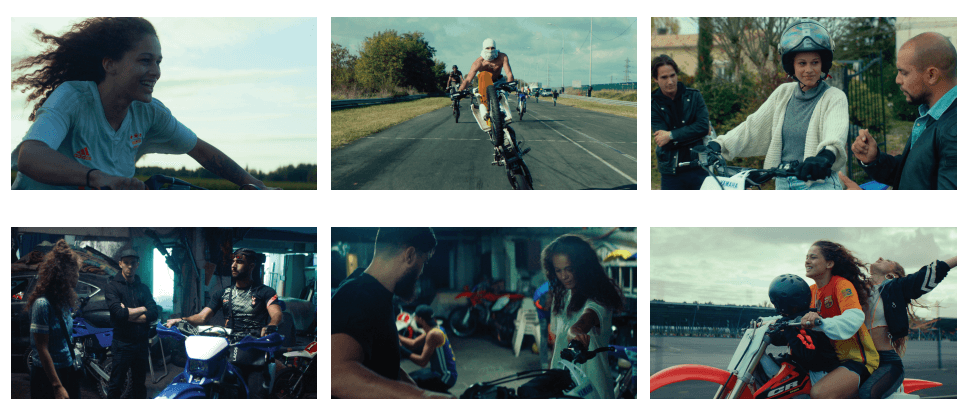

This could easily have been the start of an exploitative indie about underclass resentment and payback. But it quickly shifts gears into something more mature and complex. This is a film about people on the margins eking out a gray-market (at best) existence, confronting prejudices (sexism, racism, classism) that perpetuate ruling elite power structures, and groping for community. That this all takes place against the backdrop of bike culture, with its illegal street “rodeos” of stunts, tricks, and speed and garages full of parts, fuel, and testosterone — with a female protagonist at the center — makes the film audacious, and, more often than not, terrific.

It succeeds, in no small way, by rejecting expectations. Some have described Rodeo, which won the Un Certain Regard Coup de Coeur Prize at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival, in ways that make it sound like a fuel-injected low-budget American thriller. After all, there are bikes, heists, death. But Fast and the Furious this is not. The material stakes are extraordinarily low: Julia and the crew hijack a truck to steal three top-of-the-line bikes, not some trillion-dollar score or a world-changing thingamajig. This is low-rent crime that feels anathema to American filmmaking today.

The spiritual stakes, however, are steep and feel appropriate for a certain kind of European film. Indeed, while watching Rodeo it’s hard to imagine how it could be any more French. With its scenes inside and around hulking, dystopian, dehumanizing housing projects and focus on undesirable outsiders, it’s impossible not to see the influence of Mathieu Kassovitz’s 1995 film La haine. Similarly, like Jacques Audiard’s 2005 film The Beat That My Heart Skipped, there’s an undeniable thrum of early New Wave, particularly in how Quivoron captures Julia smoking blunts, for instance, or referring to her crew’s seen-on-video-only boss, Domino, as being in “the clink.” It’s the kind of film noir throwback style that would have been irresistible to Godard, Truffaut, and Melville.

That’s not to say Rodeo is a backward-looking, early-Tarantino-esque pastiche. It’s an achingly contemporary, bold statement on individuality and the power — and limits — of connection. Quivoron, a photojournalist, accomplishes this, in part, by shooting most of her film in a verité style, from those first chaotic moments in the projects to ecstatic scenes of guys pulling tricks on their bikes (a film unto itself) to a series of thefts building toward a final, more daring high-speed heist.

Just as important is how she conceives Julia, the axis on which the film turns. Over the film’s slim, 107-minute runtime, we’re never far from Julia or her experience of day-to-day uncertainty and precarity. Sometimes her life is grimy, others exhilarating, but it’s almost always lonely. Even after she falls in with a bike crew bankrolled by a mysterious, imprisoned criminal, Julia is a universe unto herself. She never compromises who she is or makes accommodations to others’ needs to feel powerful, especially the men of the crew. They feel emasculated because she ripped off a sweet ride? Their problem. Someone jumps her as payback for her clowning them? She’ll come at that dude with a knife. She wears what she wants, says what she wants, lives how she wants. When Kais (Yanis Lafki), the closest thing she has to a friend in the crew, asks what she’ll do with her share of the big job, she shrugs and says she doesn’t need money, she steals “all I got.”

There’s a samurai quality to Julia, living spartanly and intentionally. Even when she finds her tribe with the crew (notably after finally getting booted from her family’s apartment), she’s at a remove. One beautifully shot scene of a nighttime raver around a bonfire finds the crew blasting tunes and losing themselves totally in the experience. All the guys, and the few women that tagged along, are bunched together here and there; Julia is on her own, buffered between groups, solitarily and independently feeling the music and celebrating her way. She is with them but not of them, and probably never could be.

Her self-imposed isolation finally cracks after spending time with Ophélie (Antonia Buresi, who co-wrote the film with Quivoron) and her young son Kylian (Cody Schroeder). They also happen to be the wife and child of Domino, who controls their moves and lives from prison, dooming the nascent friendship before it really begins. Ophélie knows this, but her need for human interaction is so great that she and Kylian ride with Julia on her bike. The experience has such a profound impact that, when it comes time for Julia to leave, Ophélie bashfully and awkwardly tries to keep the moment going. She knows when Julia walks out the door, this dream will end and be replaced by the nightmarish subsistence existence Domino allows for her and Kylian.

Julia, however, is more naive and believes she and Ophélie can form a deeper relationship. Something softens within her after that bike ride. She feels a protective instinct toward Kylian and Ophélie and believes, if they could just break free of the shackles society, and Domino, have imposed, they could be themselves. And happy. And when she learns this can never be, her heartbreak is gutting — all the more so because we know that, like innumerable cinematic samurai before her, her lapse in judgment has sealed Julia’s fate.

Julia and Ophélie have a few scenes together, but the film would have benefited from a deeper exploration of their dynamic. But what we miss there Quivoron makes up for in the final moments of Rodeo, after the heist, which are some of the most confident, beautiful, and painful of the film. (There’s a scene that follows, but it feels more like a coda than a conclusion.) They’re earned by the confidence and power both Quivoron and Ledru bring to the entire film. This never feels like a first feature for either director or star. It does, however, feel like a film for the moment, fully tapped into systemic issues and contemporary struggles with a now all-too-rare rawness and honesty.

Rodeo might disappoint adrenaline junkies lured in by the promise of high-octane thrills. (Don’t worry, Fast X is on the horizon.) And anyone annoyed by the sights and sounds of motorbikes might want to stay home. (Looking at you, Mayor Adams.) But it’s firmly in the wheelhouse of those of us desperate for fresh filmmaking voices tackling tough material with style, guts, and intelligence.

Rodeo opens at Angelika Film Center, 18 W. Houston Street, on March 17.