While the African American impact on jazz is recognized and well established, the contribution of Italian immigrants on jazz is not. Italians arrived in America playing mandolin, violin, guitar and piano. They brought traditions of Southern-Italian marching bands, opera and folk histories. Whether Neapolitan, Sicilian or Calabrese, they understood passion and romanticism in music. And the Italian propensity for humor and style contributed to the theater of early jazz. In addition to outstanding musicianship, Italian performers were also entertaining.

So why do these facts go unmentioned in many mainstream jazz documentaries and literature? Ken Burns, for example, neglects to mention the impact of Italians on jazz in his popular “Jazz” documentary. He makes one mention of Nick LaRocca suggesting that LaRocca was one of the white musicians who got on the jazz bandwagon only when jazz became popular. However, Burns doesn’t mention that LaRocca wrote “Tiger Rag” and that he was one of the many influential New Orleans Sicilian musicians who forged jazz history. Even Louis Prima doesn’t get a mention. Although Burns features Benny Goodman’s version of “Sing, Sing, Sing,” he never tells us that Prima wrote it. Burns disregards the great fount of Sicilian jazz musicians that came from New Orleans and never explores conditions that put them in the creative center of the development of jazz. Consequently, people like Wingy Manone, Sharkey Bonano, Leon Rappolo, John Signorelli, Ted Fiorito, Eddie Lang, Adrian Rollini, Sam Butera and countless other Italian American artists who shaped the soul and direction of jazz in America remain obscure.

My intention here is not to provide a comprehensive history about each artist or to enumerate a list of facts and dates. My objective is to offer my personal experience with their art and acknowledge the Italian contribution to American Jazz.

Ted Fiorito

I have a special place for Ted Fiorito because of the namesake I share with him. I’m not going to lie and say that I searched him out because my dad talked about him when I was a kid. Surprisingly, the only time in my life people recognized the Fiorito name was when I worked on a retail floor in Berkeley, California just after college. WW2 retirees would look at my name tag and ask me if I was related to Ted Fiorito, the bandleader whose music piped out on the Army Broadcasts across the world. I went out to Berkeley to discover myself, to escape the world I grew up in, and there I was running smack into the old New York of my father’s childhood.

I have a special place for Ted Fiorito because of the namesake I share with him. I’m not going to lie and say that I searched him out because my dad talked about him when I was a kid. Surprisingly, the only time in my life people recognized the Fiorito name was when I worked on a retail floor in Berkeley, California just after college. WW2 retirees would look at my name tag and ask me if I was related to Ted Fiorito, the bandleader whose music piped out on the Army Broadcasts across the world. I went out to Berkeley to discover myself, to escape the world I grew up in, and there I was running smack into the old New York of my father’s childhood.

Only many years later, at about 40 years old, I found a collection of Ted Fiorito music, “Spotlight on Ted Fiorito,” on CD. I then later found another collection, “Never Been Blue.” Here and there I’ve picked up singles like “When The Lights Go On Again,” a song about soldiers returning from war, about life returning to normal after WW2.

From Ted Fiorito I became more interested in 20s music. I discovered other big bands of that era like Paul Whiteman, Ted Weems and Ben Pollack. I began to love the stylized pre-Sinatra falsetto voices of Russ Columbo and Nick Lucas. I became fascinated by the arrangements, bands playing without drums, using horseshoe clucks for percussion and tubas to hold down a bass line. I also fell in love with the vibraphone. You’ll hear the vibraphone sometimes coming in at the end of a musical stop, capping off the stop with a bell tone ring.

Fiorito played in numerous big bands and other configurations. He joined Nick Lucas in a group called The Kentucky Five in about 1915, a band consisting mainly of New Jersey Italian-Americans.

Although Al Jolson became synonymous with “Toot Tootsie,” it was written by Ted Fiorito. Some sources even show Jolson as having written it. But the fame Ted Fiorito gained from the success of “Tootsie” coincided with his co-leading a band with Dan Russo, who was already an established bandleader. From there he played in numerous incarnations with Dan Russo until he formed his own orchestra. He then recorded songs like “Simple and Sweet,” “I’ll Take an Option on You,” “Soothing,” “I’ll String Along with You,” and countless others.

In the 30s, Fiorito teamed with the “Debutantes” vocal trio and brought in guitarist Muzzy Marcellino and bassist Candy Candido, both of whom would become equally known for their vocals. Marcellino had an unusually clear and melodious whistle. His whistling was featured on Mickey Mouse and Lassie, and even The Good, The Bad and The Ugly soundtracks. Marcellino was also the uncle of Vincent Guarldi, the pianist and songwriter associated with the music of “Peanuts.” Candy Candido, born in New Orleans, provided unusual voices in films like Abbot and Costello in the Foreign Legion and others. Even Betty Grable briefly joined Fiorito’s band. Though she didn’t make any recordings with Fiorito, she appeared as a vocalist in the 1933 film “The Sweetheart of Sigma Chi.”

At the peak of his popularity, Fiorito managed to succeed as a composer and bandleader and performed his songs in film.

Towards the end of his career, Fiorito moved to Scottsdale, Arizona, where he opened the Black Sheep Club. He continued to play in California and Nevada in different band incarnations until his death in 1971.

Adrian Rollini

Ask the first ten people you know who consider themselves music experts if they’ve ever heard of Adrian Rollini.

Ask the first ten people you know who consider themselves music experts if they’ve ever heard of Adrian Rollini.

Rollini was a hub for music in the 20s and 30s, playing with Annette Hanshaw, Cliff Edwards (Ukelele Ike), Frank Signorelli, Joe Venuti and his Blue Four, Miff Mole, Red Nichols, Bix Beiderbecke, Frank Trumbauer and many others. Read the personnel listings on recordings from the 20s and 30s; you’ll see Rollini’s name often appearing. In fact, Rollini, Lang, Signorelli, Venuti, Trumbauer, and Bix played in many of the same configurations.

Born in Larchmont, New York in 1903, Rollini was considered a child prodigy. He was dubbed Professor Adrian Rollini at age 4, playing Chopin‘s Minute Waltz at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel. He played piano, bass saxophone, chimes and vibraphone, all extremely well. I don’t see him credited for playing piano on recordings. He was credited for bass saxophone and vibraphone. The bass saxophone is an unusual instrument; I’m not exactly sure why anyone would want to learn it, except for the fact that it’s so novel. It’s difficult to even hold, much less play. The bass saxophone was more commonly used in orchestral music giving richness and depth to brass harmony arrangements.

Rollini also became an early master of the vibraphone, where he played behind many prominent jazz musicians, some already mentioned. Initially recognized for its novelty effects, vibraphone was then added to the arsenal of percussion sounds used by vaudeville orchestras. The vibraphone soon became a jazz instrument standardly employed for its dreamy percussive ring. Unlike its cousin the xylophone, the vibraphone is not a solo instrument. As only he could, Rollini wrote “Vibrolinni,” a completely untypical composition for the instrument. The vibraphone provides atmosphere and color but doesn’t stand out as a featured jazz instrument. Despite this, Rollini pushed his playing of the vibraphone into exciting new directions.

In addition to playing as a sideman on notable artists’ records, I have a collection of Rollini 1934-1938 recordings that has songs like “Davenport Blues,” “Bouncin’ In Rhythm,” “Honeysuckle Rose,” and others. It’s a good collection but doesn’t give you the depth and breadth of the man’s great career. Rollini is the gem hidden in the songs of the 20s and 30s.

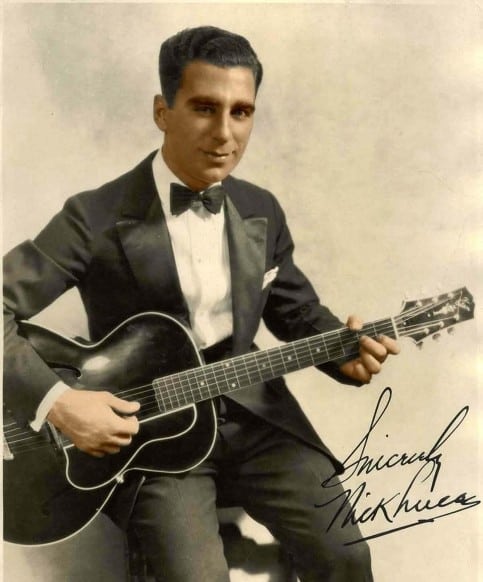

Nick Lucas

When I play Nick Lucas for people, often their first reaction is a chuckle. His choice of songs, though once standards, now sound corny and old fashioned. Also, he sings in a stylized falsetto like many pre-Sinatra popular vocalists of his time. The Nick Lucas collection I have is mainly solo works on guitar and vocals with songs like “Tiptoe Through the Tulips.” Accompanying himself on guitar he can stand in front of the audience, making the guitar more intimate than the piano. His chord progressions are innovative and dynamic, giving the guitar the power to front an orchestra. Using the jump rhythms of jazz guitar, he also picks out the melodies to compliment his vocals. A guitar player can tell that he learned banjo before the guitar by the way he alternates his index and forefinger while using his thumb to maintain tempo. This ragtime style would be one of the branches of guitar evolution which would further develop in the hands of guitarists like Merle Travis and Chet Atkins.

When I play Nick Lucas for people, often their first reaction is a chuckle. His choice of songs, though once standards, now sound corny and old fashioned. Also, he sings in a stylized falsetto like many pre-Sinatra popular vocalists of his time. The Nick Lucas collection I have is mainly solo works on guitar and vocals with songs like “Tiptoe Through the Tulips.” Accompanying himself on guitar he can stand in front of the audience, making the guitar more intimate than the piano. His chord progressions are innovative and dynamic, giving the guitar the power to front an orchestra. Using the jump rhythms of jazz guitar, he also picks out the melodies to compliment his vocals. A guitar player can tell that he learned banjo before the guitar by the way he alternates his index and forefinger while using his thumb to maintain tempo. This ragtime style would be one of the branches of guitar evolution which would further develop in the hands of guitarists like Merle Travis and Chet Atkins.

Born Dominic Nicholas Anthony Lucanese in 1897 in New Jersey, he later changed his name legally to Nick Lucas. Nick’s older brother Frank taught him music without any instrument using the solfeggio system. The idea behind solfeggio is that you first learn to sing a song before you play it on an instrument. This very Italian form of musical education has had a tremendous impact on Italians in music, particularly Italian-Americans. By never forgetting the melody, a musician can express the story of a song in instrumentation. A violin can weep, a guitar can gurgle like a brook, and a banjo can dance. Once Lucas mastered the solfeggio system, he then learned how to play the guitar, mandolin and banjo all while still very young.

According to Lucas, his brother Frank dragged him along to play at Italian christenings and weddings. “We even played on street corners and in saloons and I’d pass the hat around. I was getting a lot of experience because the Italian people, when they get to feeling good, like to dance all night long, especially the tarantella. We played for hours and hours, and my wrists got very tired, but I was getting great practical experience that paid off years later.”

Lucas switched from tenor banjo to guitar after playing with his brother. He even played in The Kentucky Five and in the Russo-Fiorito Orchestra in the early 20s. He became known as “The Crooning Troubadour.”

After cutting a string of hits on the Brunswick Label, he was then signed by Warner Brothers to sing “Gold Diggers of Broadway.” In this film he sang, “Painting the Clouds with Sunshine” and “Tiptoe Through the Tulips with Me.” During “Tiptoe” the dancers actually weaved through red and yellow tulips as Nick sang. “Tiptoe Through the Tulips with Me” sold three million copies in its initial pressing as a record and has since sold five million copies.

Lucas has had a lasting impact on the guitar. Listening to it today, his guitar playing still sounds inventive. Lucas developed a whole new vocabulary for guitar accompaniment; his ideas are still being assimilated by guitarists.

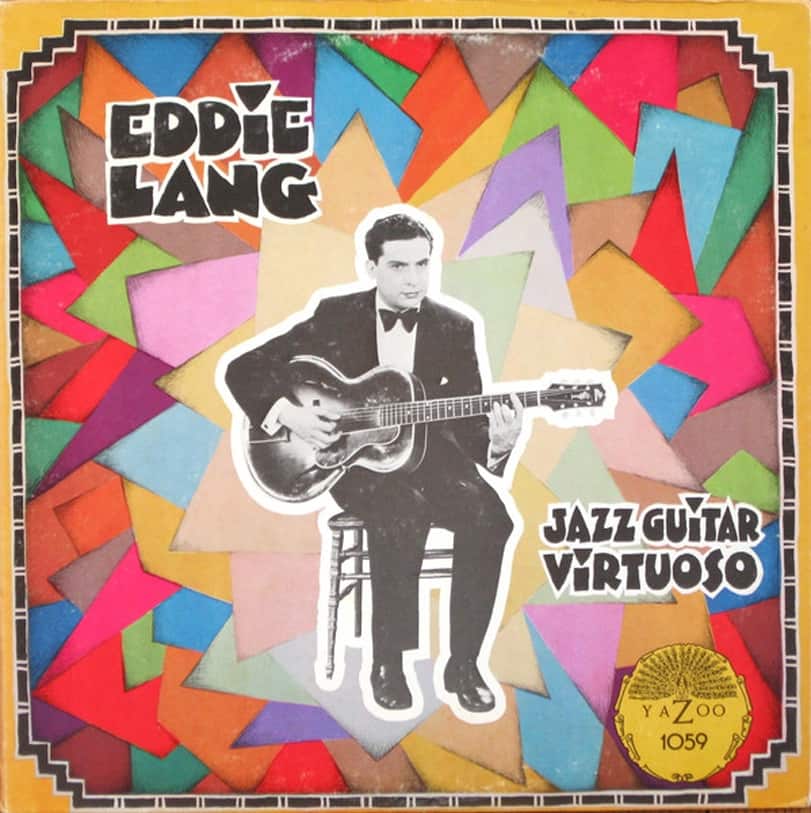

Eddie Lang

Among those listening to Nick Lucas was Eddie Lang. Born Salvatore Massaro in 1902 in Philadelphia, PA, he is considered the Father of Jazz Guitar, though he may not be well known today except among specialists. You can see a performance of Eddie Lang and Ruth Etting on YouTube from their 1932 film “A Regular Trouper.” His guitar playing is subtle and dancelike; he never gets in the way of a vocalist. He could offer a light touch, or dazzle with a thumping rhythm, moving with the changing dynamics of a vocalist. As such, vocalists often worked with Lang. In addition to Etting, Lang played with Bing Crosby, Bessie Smith and countless others. He was a vocalist’s guitar player.

I have a collection of Eddie Lang’s solo guitar works called “Jazz Guitar Virtuoso.” As it comes through on my shuffle, hearing individual songs out of context, it can be hard to identify a song I haven’t memorized. There are elements of jazz, Delta blues and even bluegrass in Lang’s playing. In the mix of all of these American styles, Lang added perhaps a bit of Neapolitan romanticism. Lang could play anything.

You might say that Lang killed the banjo. After Lang demonstrated that the guitar could be sophisticated, the banjo slowly disappeared from jazz orchestras. The advent of the electric recording for the guitar allowed it to develop a wide range of guitar sounds, from honking brass tones to rounder, softer accompaniment. Lang set the direction for what jazz guitar could be. Django Reinhardt, Les Paul and Charlie Christianson all benefited from Lang’s trailblazing chording techniques.

Unsurprisingly, Lang initially played violin, taking lessons for 11 years. In school he became friends with Joe Venuti, who was a lifelong collaborator. By 1918, he was playing violin, banjo, and guitar professionally. He worked with various bands in the US, briefly played in London, then settled in New York City.

On February 4, 1927, Lang was featured in the recording of “Singin’ the Blues” by Frankie Trumbauer and His Orchestra with Bix Beiderbecke on cornet. He was in the center of the storm.

In 1929, while with the Paul Whiteman Orchestra, Lang was introduced to Bing Crosby who was then an up-and-coming vocalist. They developed a close personal relationship which would propel Lang’s career.

When Crosby signed a five-picture deal with Paramount Studios, he insisted Lang share the experience with him. Lang, playing guitar accompaniment, appeared with Crosby in their 1932 Hollywood feature film “The Big Broadcast.”

Like Rollini, Lang played with numerous artists through his brief career. He is the quintessential jazz guitar player of the 20s and 30s.

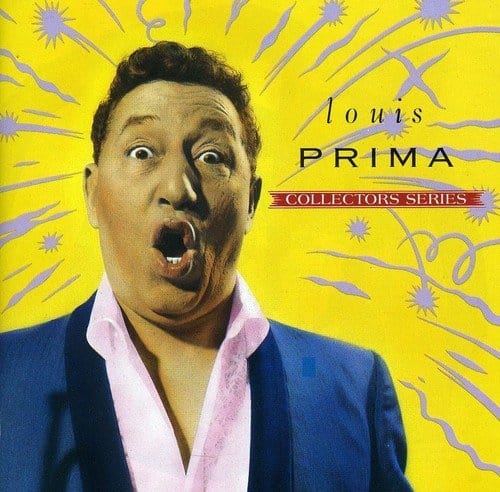

Louis Prima

I remember as a kid dancing to “Buona Sera,” “Please Don’t Squeeze the Banana,” and “Just A Gigolo.” My mom had a Prima Greatest Hits record that we would go crazy listening to when all of the company left after Christmas.

For most of my life, Prima was a clowning musician who made some funny music. I didn’t know how good a trumpet player he was or anything about his history.

Then I started to dig and learn more and more about his history and his music. I read a book called “Louis Prima” by Gary Boulard and learned Prima’s dirty little secret. Because Sicilians weren’t considered to be white, the white establishment wasn’t concerned if Sicilians lived and played among blacks in New Orleans. So, Prima and many other New Orleans Sicilians played in the homes, streets and bars of Storyville, learning the jazz idiom. The Italians in Storyville also brought their language and humor to the music. Prima combined his Sicilian dialect with rhythms and harmonies of jazz to make songs like “Please Don’t Squeeze the Banana,” “Angelina,” “Buona Sera,” and others. His music allowed for a private joke among the growing Italian American population in America. They knew the lyrics were slightly off-color. They understood that when Prima sang “Zooma, Zooma Baccala” he wasn’t referring to fishing. But most of all, the songs were entertaining. Prima had to change with the times, performing in smaller ensembles before the war, then playing in big bands, then playing in smaller ensembles again. The musicians and arrangements were tight, combining the dizzying rhythms and time signatures of New Orleans with comedy and theater.

Sharkey Bonano

Arturo Toscanini heard Sharkey in New York then hired him to come to a rehearsal of the New York Philharmonic to play a few solo numbers for his orchestra. After Sharkey played, Toscanini berated his trumpet section at length because they couldn’t blow tones out of their instruments like Bonano.

Also known as Sharkey Banana or Sharkey Bananas, he was a jazz trumpeter, band leader and vocalist.

Joseph “Sharkey” Bonano was born in the Milneberg section of New Orleans in 1904. Milneberg had scores of cabarets on the boardwalk overlooking the water. Here, white and black jazz musicians listened and stole each other’s performance styles and ideas.

Bonano played lefthanded like Nick LaRocca. He amused his audiences with his shimmy dances and comical routines. Out of the many white New Orleans jazz musicians like Leon Roppolo, Tony Parenti, and Santo Pecora, Sharkey distinguished himself with his terrific tone and entertaining style.

Riding out the Depression playing in small clubs around New Orleans, Bonano finally landed a residency at Prima’s Penthouse. When Prima’s Penthouse folded, he was lucky enough to attract the attention of a Greenwich Village tavern owner, Nick Rongetti.

Bonano wrote a number of classic tunes like “Yes She Do-No She Don’t,” “I’m Satisfied with My Gal,” and “Wash It Clean.” He also recorded popular songs of the day like “When You’re Smiling,” “Panama,” and countless others.

At the end of his career, Bonano returned to his hometown, New Orleans. He became a wildly successful tourist attraction. In some respects, he was at the height of his career at this point, well established in New Orleans jazz history. He never stopped his shimmying and strutting until the end.

Wingy Manone

“Rhythm is Our Business” is the quintessential statement for Italians in New Orleans. Rhythm, virtuosity, style and theater describe the Italian American contribution to jazz as typified by Wingy.

Wingy was born in New Orleans in 1900. Like Prima, he was a dazzling trumpet player, often interspersing patter with virtuosic trumpet leads. Unlike Prima, he frequently played as a sideman on recording sessions, though he also performed as a bandleader.

At the age of ten, he lost his arm in a streetcar accident. Afterwards, he was cruelly called “Wingy” by the people he knew. Playing the trumpet with one arm, Wingy broke his teeth playing on Mississippi River Boats. He then moved on, playing in New York, St. Louis and Chicago.

Like Prima and Bonano, Wingy was a highly skilled musician who entertained his audiences. Just listening to his recordings “Wingy Manone and His Orchestra 1935-1936,” and “Wingy Manone and His Orchestra 1944,” you hear the comic vocal style and humorous lyrics.

For many years, Joe Venuti sent Wingy a single cufflink on his birthday as a practical joke.

Leon Roppolo

When you listen to the early classic recordings of the New Orleans Rhythm Kings, you hear the searing melodic solos of Leon Roppolo’s clarinet emerging from the fray of Dixeland band sounds. I personally find it magical that you can connect with 100-year-old sounds recorded on poor quality technology, and without the benefit of modern recording techniques. Roppolo’s clarinet rises like heat from the records. An ear that is not listening will not hear the powerful artistic genius of his clarinet. Someone who is listening will hear the brilliant high notes and the sheer energy projected across time, pushed out with explosive urgency. You can imagine Roppolo standing in front of a microphone twisting and contorting, playing with all of the intensity of a live performance. Recording was a relatively new art. Who knew how to arrange instruments and solos in the recording industry? “Make it sound live, give energy and vibrancy,” is probably the direction the players were given.

Leon Roppolo was born March 16, 1901. Best known for his playing with the New Orleans Rhythm Kings, Roppolo also played saxophone and guitar.

Leon Joseph Roppolo was born in Lutcher, Louisiana near New Orleans. His family of Sicilian origin moved to the Uptown neighborhood of New Orleans about 1912. Roppolo first learned music playing the violin. This is a very common Italian American phenomenon: bringing classical training and tonality into jazz. He was a fan of the Italian and non-Italian marching bands he heard in the streets of New Orleans and, as such, identified strongly with the clarinet.

Bringing the knowledge of music, he developed from violin, Roppolo soon excelled at the clarinet. He played with his childhood friends Paul Mares and George Brunies for parades, parties, and at Milneburg on the shores of Lake Pontchartrain. In his teens Roppolo decided to leave home to travel with the band of Bee Palmer, which soon became the nucleus for the New Orleans Rhythm Kings. The Rhythm Kings became (along with King Oliver‘s band) one of the best regarded hot jazz bands in Chicago in the early 1920s. Many considered Roppolo to be the star. His style influenced many younger Chicago musicians, most famously Benny Goodman. Some critics have called Roppolo’s work on the Rhythm Kings Gennett Records, the first recorded jazz solos.

After the breakup of the Rhythm Kings in Chicago, Roppolo and Paul Mares headed east to try their luck on the New York City jazz scene. Contemporary musicians recalled Roppolo making some recordings with Original Memphis Five and California Ramblers musicians in New York in 1924. These sides were presumably unissued, or if issued, unidentified.

Roppolo and Mares then returned home to New Orleans where they briefly reformed the Rhythm Kings and made some more recordings. After this, Roppolo worked with other New Orleans bands such as the Halfway House Orchestra, with which he recorded on saxophone.

In his later life, Roppolo, looking old and feeble far beyond his age, would come home for periods when a relative or friend could look after him and he would sit in with local bands on saxophone or clarinet.

Frank Signorelli

Frank Sinatra sings a version of Frank Signorelli’s “I’ll Never Be the Same” that goes right into your soul. The melody hooks into your head. Eddie Lang recorded a guitar version of it capturing a different mood of the melody. In Lang’s hands it’s less melancholy and more playful. Signorelli also wrote “Stairway to the Stars,” and “A Blues Serenade” in the ‘30s. Sadly he was otherwise scarcely recorded.

Frank Signorelli was born in 1901 in New York City. Like many of the musicians in this review, Signorelli was an important player behind the scenes and an accompanying pianist with several notable bands. Many of these musicians played in the same ensembles and backed bigger named artists on countless records. Signorelli appeared on many classic records with Bix Beiderbecke, Frankie Trumbauer, Joe Venuti, and Eddie Lang during the era, plus on a countless number of recordings with dance bands and backing commercial singers. In 1917, with Phil Napoleon, he was a founding member of the Original Memphis Five. Signorelli was briefly a member of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band in 1921. In 1927, he was in Adrian Rollini’s legendary New Yorker group. He played with a newer version of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band (1936-1938), worked with Paul Whiteman for a few months in 1938, and played regularly during the ‘40s and ‘50s (including at Nick’s with Bobby Hackett) and helped organize the revived Original Memphis Five.

Mike Fiorito is currently an Associate Editor for Mad Swirl Magazine. His most recent book, Call Me Guido, published by Ovunque Siamo Press, explores three generations of an Italian-American family through the lens of the Italian song tradition. As poet Joey Nicoletti (Thundersnow) writes, these are “the stories of relatives, potato farmers, performers, imagined aristocrats, and the ballads they sing.” John Keahy (Seeking Sicily) says, “This collection, in quick bites, informs, entertains, and surprises—a masterpiece of storytelling.”

His short story collections, Hallucinating Huxley and Freud’s Haberdashery Habit, were published by Alien Buddha Press.

His writings have appeared in Ovunque Siamo, Narratively, Mad Swirl, Pif Magazine, The Honest Ulsterman, Chagrin River Review, The New Engagement and many other publications.

For more information, please visit: callmeguido.com Or email callmeguido2@gmail.com