Go to a mirror. Look into your eyes—the same ones you had as a child. When you look into them, whom do you see?

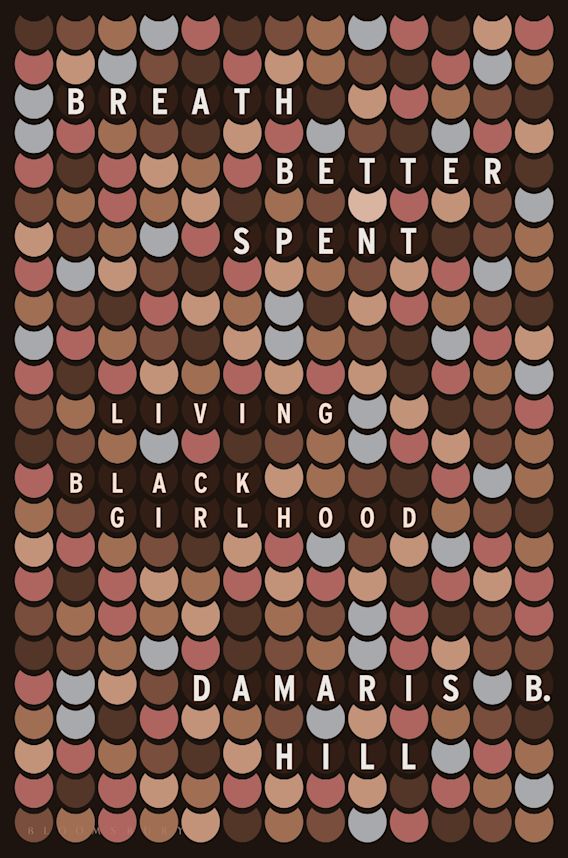

Breath Better Spent: Living Black Girlhood, DaMaris B. Hill’s new book of narrative poems, fulfills a pledge the author made to not only acknowledge the child within, but “to carry my girl self on my shoulders and celebrate her.” The book underscores the absolute need for love—especially self-love—and emphasizes, as the center of our lives, the importance of storytelling: sharing our own and passing down the ones we know.

The stories Hill shares locate her life on a continuum. There are tributes to the women whose shoulders she stands on—many of them enslaved. Then there are “semi-autobiographical” accounts of her American childhood in the 1980s and ’90s, where she looked up to women like Aretha Franklin and Whitney Houston. Finally, there are meditations on the grief of the present moment, where young Black girls disappear and people don’t seem to notice or care. Hill’s poems remind us that we are creating our future through the actions we take—or don’t take—now.

In a poem that serves as a kind of preface to the collection, Hill writes, “Your first grown-up job / is to keep a secret about /dead people among us.” In other words, don’t talk about slavery, don’t talk about the enslaved. But her girl self is fidgety and curious. Questions pop out. Who were these people? It’s obvious they forged paths for us to follow—and we may follow these paths, without ever thinking about who made them, without ever knowing their names. Hill teaches them to us. She celebrates women like Phillis Wheatley (an enslaved woman who became a well-known poet), Jarena Lee (a domestic servant who became the first female preacher in the African Methodist Episcopal Church), and Ma Rainey (known as the “Mother of the Blues”).

Hill teaches us her story as well. Born late, but underweight and ravenous, her hunger develops into an insatiable appetite for knowledge. It sets her apart from the other girls—“I am smart and have learned the rewards system that skirts beauty”—but everyone likes to feel attractive and feel like they fit in. Memories of Hill’s childhood conjure jelly bracelets and sandals, fruit-flavored lip gloss, and a “puffy ponytail that is always wiggling out of barrettes.” Her pre-teen body is awkward—belly like “an underripe watermelon,” developing breasts like “daisies”—and puberty is a swamp of conflicting, confusing feelings: “swaying / in Elmer’s glue between good girl and what you think is / grown.”

In adolescence, we are often eager to abandon ourselves as children. Yet our adult bodies can warrant attention our child selves are unprepared for. Sometimes they make us feel powerful, as when Hill’s narrator discovers that other girls’ boyfriends desire her. Sometime they make us feel powerless: One minute Hill’s middle-school-aged narrator is laughing and walking down the street with her best friend, the next a stranger grabs and squeezes her breast and runs off. “Bestie tells me to ‘shake it off.’ Tells me ‘it is nothing.’ And that ‘it would happen all the time and over again.’ Twisting my head ‘no,’ I believe her and now I wonder how she knew.” Incidents like these become representative: “personal experiences within a collective Black girlhood,” Hill writes.

The center of this middle section is “Born Again and Again.” We know something different and important is happening here because we have to turn the book sideways, like a centerfold. It’s an epic poem that weaves together the story of Hill’s life, her father’s, their ancestors, as well as fictional characters and the writers who birthed them. At age three, Hill’s narrator is killed in a car crash. Her grandmother stands distraught over the little girl’s body in the hospital while “doctors tell her ‘breath is better spent on the living.’” Well, no thanks to them, the poem seems to say, the girl lives—resurrected and kept alive by the prayers of her grandmother.

Women keeping other women alive is another theme that emerges in Breath Better Spent. In the preface, Hill acknowledges three groups that have kept her going: Saving Our Lives, Hear Our Truths (SOLHOT), a collective that celebrates Black girlhood; Urban Bush Women (UBW), a dance theater ensemble that spotlights the African Diaspora; and Philadelphia’s Colored Girls Museum, which showcases donated objects that speak to their owners’ experiences of Black girlhood. Throughout the book are touching black-and-white photos of both famous women (Aretha, eyes closed, belting into a microphone) and unknown girls (one has her eyes and mouth wide open, as if happily surprised).

One of the museum’s exhibits inspired a series of laments by Hill for all the Black girls around the world who disappear without an outcry, as if it didn’t matter that they were ever here at all. These poems hold up a different kind of mirror. Beyond the self, they show us “America.” They show us “who we are as a nation.” And if we don’t turn away in self-disgust, we may look deeper and discover the things about ourselves truly worth loving.

Look in that mirror. Lean in close. Now exhale. “Breath is both individual and profoundly communal—particularly in the form of language,” Hill writes. “Breath is a type of life force. One that is both physical and spiritual.” Every one of us is dependent on the next one, and the one after that, just as our childhood selves are dependent on us seeing them and remembering: Everyone is deserving of love.

Quinn on Books: Review of Breath Better Spent by DaMaris B. Hill

READ OUR FULL PRINT EDITION

Our Sister Publication

a word from our sponsors!

Latest Media Guide!

Where to find the Star-Revue

How many have visited our site?

Social Media

Most Popular

Big donors taking an interest in our City Council races

Wraptor celebrates the start of spring

Related Posts

Special birthday issue – information for advertisers

Author George Fiala George Fiala has worked in radio, newspapers and direct marketing his whole life, except for when he was a vendor at Shea Stadium, pizza and cheesesteak maker in Lancaster, PA, and an occasional comic book dealer. He studied English and drinking in college, international relations at the New School, and in his spare time plays drums and

PS 15’s ACES program a boon for students with special needs, by Laryn Kuchta

At P.S. 15 Patrick F. Daly in Red Hook, staff are reshaping the way elementary schoolers learn educationally and socially. They’ve put special emphasis on programs for students with intellectual disabilities and students who are learning or want to learn a second language, making sure those students have the same advantages and interactions any other child would. P.S. 15’s ACES

Big donors taking an interest in our City Council races

The New York City Council primary is less than three months away, and as campaigns are picking up steam, so are donations. In districts 38 and 39 in South Brooklyn, Incumbents Alexa Avilés (District 38) and Shahana Hanif (District 39) are being challenged by two moderate Democrats, and as we reported last month, big money is making its way into

Wraptor celebrates the start of spring

Red Hook’s Wraptor Restaurant, located at 358 Columbia St., marked the start of spring on March 30. Despite cool weather in the low 50s, more than 50 people showed up to enjoy the festivities. “We wanted to do something nice for everyone and celebrate the start of the spring so we got the permits to have everyone out in front,”