There’s lots to love when it comes to Blue Note records, not the least of which is that the combination of the consistently fine music they recorded and released and the distinctive and influential graphic design of the record albums were some of the most important elements of creating what “cool” meant in American culture, before it was coopted and perverted by the idea that making money and buying things—rather than standing askance to square, consumerist society—is somehow cool.

Put on a Blue Note disc and you’ll be digging the music. Pull back into the mountain-top view, and survey the landscape of recorded music, and you’ll see that every record is a document of some historical moment, which can be as fine grained as an afternoon in Rudy Van Gelder’s studio or as complex as the personal and social circumstances that inform the moment when a musician steps up to the mike and their human experience pours out through an improvised solo. Then take all those Blue Note discs and put them into a quilt, and you’ve got one of the most important and informative aesthetic narratives in 20th century music and culture. Now open up that quilt for two more new archival issues from major voices in that story, and relive both the moments and see the panorama with greater detail, depth, and clarity.

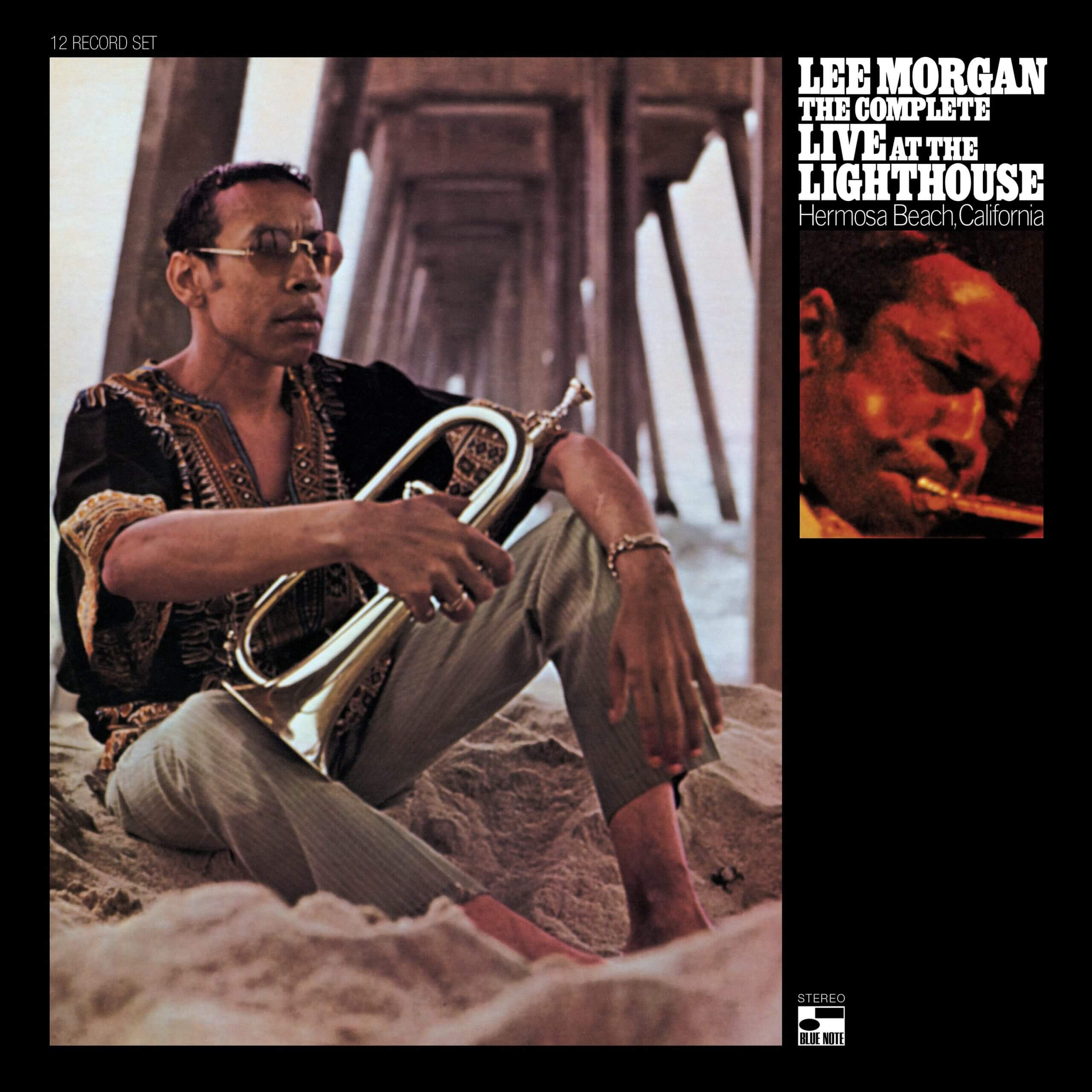

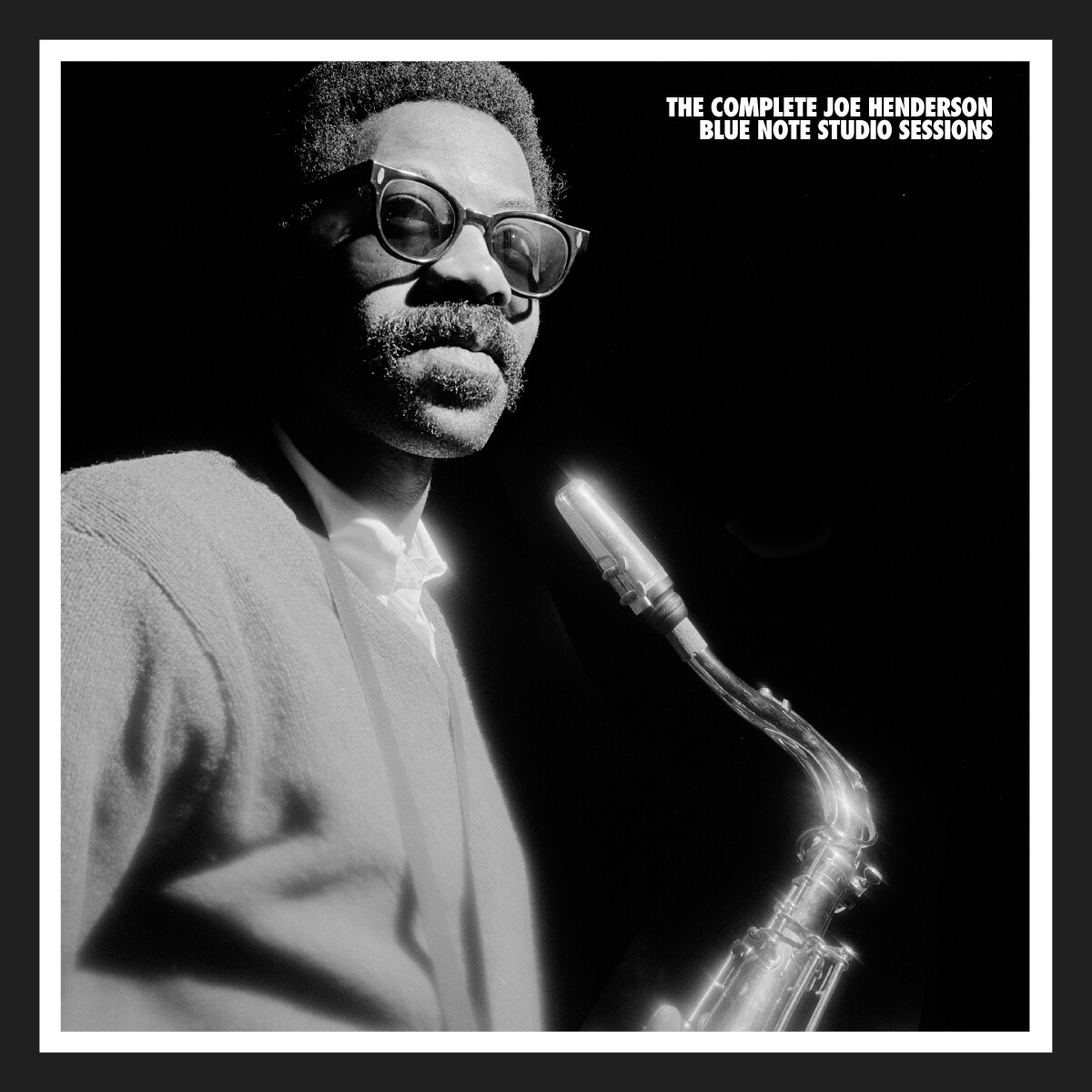

Out as of this late summer are, on Blue Note, The Complete Live at the Lighthouse, from trumpeter Lee Morgan, and The Complete Blue Note Joe Henderson Studio Sessions, in limited release, licensed from Blue Note, on the specialty Mosaic Records label (www.mosaicrecords.com). Mosaic producies deep-dive, limited edition box sets with excellent remastering and large-scale, comprehensive booklets full of essays, analysis, beautiful photographs and detailed discographical information. The Henderson set is up there with their usual standards and is full of one great track after another, across five CDs. But there’s one major caveat to this collection: this is nowhere near the complete Blue Note studio sessions from Henderson, and I have no idea why it’s titled as such.

The set runs from trumpeter Kenny Dorham’s Una Mas album, recorded April 1, 1963, through Henderson’s Mode for Joe, featuring Morgan in a group that sounds like a modernized version of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, though with Joe Chambers on drums and the addition of the great vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson. That session took place January 27, 1966. Bob Blumenthal writes in the booklet that, “This collection contains all of Henderson’s own Blue Note albums and the pair he made with Dorham, plus a sampling of the original compositions he contributed while recording with others.”

That last clause explains the absence of great albums like Grant Green’s Idle Moments and Andrew Hill’s Black Fire, and Morgan’s own The Sidewinder, one of the great jazz albums of all time. But it confuses things also, because Henderson doesn’t have any writing credits on Una Mas. The saxophonist also released two Blue Note albums, Page One and Our Thing, beforeInner Urge, from 1964, which is in this set and is a mid-‘60s classic and highly influential. This is far from complete and the explanation is frustrating in the way it obfuscates both the truth and its own logic.

That aside, there’s nothing but musical pleasure in here. Like Henderson, Dorham is perhaps in the second rank when it comes to name recognition but remains one of the all-time greats. The pleasure of hearing these two together is that they were both smart and tough-minded players, constructing sophisticated musical ideas on the fly with power and a respect for sensation, the epitome of great jazz playing. Henderson has one of the most distinctive sounds in jazz, punchy, warm, light and quick as a jab but with the weight of a haymaker.

The capsule journey from Inner Urge, and the elevated blues of the title track, to the whole of Mode for Joe, is one of the stories of modern jazz in the ‘60s, with hard bop expanding, through the influence of free playing on the one hand and composing that moves away from standard 12-bar blues and AABA song forms and assembles more complex rhythms, harmonies, and shapes (listen to Jackie McLean’s and Wayne Shorter’s Blue Notes from the same period for more of that story). The harmonies and forms on Mode for Joe are expansive, the players are willing to stretch outside linear phrases into musical gestures that reach into raw emotion, but the swing and swagger of hard bop are all there. There’s never a dull moment in this set, and while the gap between what the title promises and the contents deliver is too wide for it to tell us anything new about Henderson, the music is so good that it’s a major release.

Lee Morgan was a real star in the 1960s. He made his debut recording sessions the first week of November, 1956, when he was 18 years old, and two years later is a dazzling presence on John Coltrane’s Blue Train. He is all over the Blue Note catalogue in the decade, with giant hits like The Sidewinder and The Rumproller, tremendous artistic statements like Search for the New Land, on the frontline, with Shorter, in the Jazz Messengers, and as the kind of featured sideman who helped make albums from musicians like Clifford Jordan, McLean, Hank Mobley, Shorter, and Jimmy Smith part of the central story of jazz.

Morgan was fiery, fluid, absolutely on top of post-Charlie Parker idioms while also deep in the blues and funk. He didn’t experiment with the avant-garde, but he did move his own music forward as jazz incorporated rock, soul, funk, and other pop ideas as the ‘60s came to a close. Until now, there were only hints of that in his discography (his story ended February 19, 1972, when his common-law wife, Helen, shot him to death at Slug’s Saloon—the culmination of the 2017 documentary film I Called Him Morgan). He left behind a final session and a tantalizing live double-album, Live at the Lighthouse.

Blue Note has now put out the complete version of that, eight CDs with 12 sets across four days at Hermosa Beach, CA, club. It’s stupendous. Morgan was right there in the center of the music, in the summer of 1970, pulling together hard bop, latin jazz, pop ideas (he quotes “Eleanor Rigby”) and rock rhythms, and some gorgeous, rich harmonies. Some of the styles may sound dated, particularly the arrangement of “I Remember Britt,” but the intelligence, strength, and explosive excitement of the playing are timeless and eternal—the mainstream of modern jazz still sounds like this record, 50 years later.

Morgan plays exceptionally well, no surprise there, even when he was struggling with drugs he always played with energy and had meaningful things to say. The revelation is getting to hear so much of Bennie Maupin, who plays tenor sax, flute, and bass clarinet. Maupin is a central part of some of the most important jazz albums of the last half century, including Bitches Brew and Head Hunters, but outside of those records it’s hard to get to hear his playing. This release cements his status as a musician of substance. His muscular, leathery tenor sound is as distinctive in jazz as Henderson’s, and his sophistication and power are just as fine. He’s a great ensemble player on all his horns, and when it’s time to come to the fore, his soloing is probing and full of the propulsive excitement of the moment. This is a massive amount of tremendous live jazz, and Maupin is as responsible for that as Morgan.

Author

-

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/

View all posts

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/