On November 28, Studio 153 on Coffey Street held the opening of the exhibition “Blue City,” which inaugurated the conceptual phase of a long-term plan by the nonprofit RETI Center to build a cluster of “sustainable floating structures” at the Gowanus Bay Terminal (GBX). The development will be “the first of its kind in New York City.”

Based in Red Hook, the RETI (Resilience, Education, Training, and Innovation) Center aims to steer economic development in New York toward projects that will help the city withstand rising sea levels and extreme weather while also ameliorating the social disparities that render some communities particularly vulnerable to the impact of climate change. According to executive director Tim Gilman-Ševčík, a professor at NYU’s Stern School of Business, the RETI Center was “started out of interest by Pratt Institute to replicate a place that they’d found in Rotterdam called the RDM Campus,” a former shipbuilding facility in the Netherlands that now hosts cutting-edge private industry, education programs, and environmental research initiatives.

Founded in 2015 by architect Gita Nandan, RETI earned its first grant from the Governor’s Office of Storm Recovery to provide solar panel installation training for unemployed and underemployed youth from the Red Hook Houses. The training was completed last summer, but RETI has yet to find a permanent home for its operations.

To that end, RETI has formed a partnership with GBX. “Essentially, they called us out of the blue,” Gilman-Ševčík recalled. GBX owner John Quadrozzi Jr., whose father bought and rebranded the Port Authority’s long-abandoned Red Hook Grain Terminal in 1997, rents out portions of the land to industrial and maritime tenants (as well as film production crews), but the property also encompasses 33 acres of water.

Per Gilman-Ševčík, Quadrozzi “wanted to do something that combines social justice and sustainability and would actually activate their site more in terms of their ability to bring in the public.” RETI suggested putting a “climate change lab” directly on Gowanus Bay, which, owing to its remove from GBX’s heavier land-based industry, would allow for a safe, separate point of entry for visitors.

In 2012-2013, the Red Hook community rejected Quadrozzi’s bid to extend the Gowanus Bay Terminal seaward by the addition of cement encasements of toxic sludge from the Gowanus Canal cleanup. The Blue City plan offers a new and perhaps more agreeable means for GBX to take advantage of its unused acreage beyond land’s end.

“Because GBX is a concrete manufacturing company, our intention is to use concrete as the primary floating mechanism,” Gilman-Ševčík said. “The plan is to build it with community involvement, in that we’d actually be running training courses, like we have in the past, for the construction of it, so we’d be teaching people to build it while building it.” He believes that this on-site assembly process, if successful, could ultimately yield a separate construction business, specializing in the fabrication of similar modular floating structures and employing Red Hook Houses residents.

The EPA has cited concerns regarding the effects that permanent offshore structures — and the shadows that they cast on the water — can have on the health of seafloor ecosystems, which means that acquiring permits will be a challenge for Blue City as RETI seeks out an environmentally friendly design. Due to additional questions of funding, no firm timeline has emerged thus far for the completion of the project. A small RETI Center structure may appear at GBX before the larger Blue City vision is realized, possibly within 18 months.

Once completed, the RETI Center’s permanent headquarters will provide job training, educational workshops, lectures, and art exhibitions, in addition to conducting climate change research and sustainable technology development, for which manufacturing will occur largely on shore to avoid problems posed by waves. The offshore structure, however, will allow for specifically aquatic activities such as mussel growing; water testing; and phytoremediation, a process that uses living plants to purify contaminated water.

“Definitely the uniqueness of it is very important in order to attract people to it and get attention and funding, because it would be very innovative,” Gilman-Ševčík commented. The project may also serve as a blueprint for a living-with-water approach to flood management, a concept whose popularity has grown as the possibility of keeping storm surge out of coastal cities diminishes.

The RETI Center expects other tenants to come to Blue City, believing that the waterborne development could be attractive for the purposes of recreation and urban farming. And since the RETI Center will be off-grid, using solar energy, Gilman-Ševčík hopes that the prospect of “cross-fertilization” may draw green energy companies to the site.

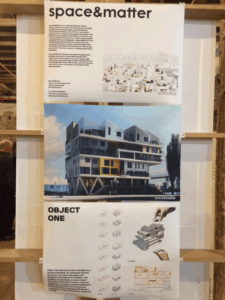

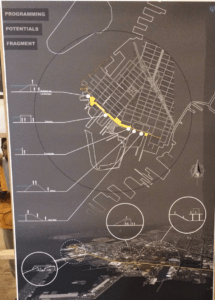

The exhibition at Studio 153 showcased possible designs for the RETI Center by Pratt undergrads, alongside diagrams and architectural renderings by the Dutch firms Space&Matter and One Architecture & Urbanism, which will join Oasis Design Lab, Nandan’s thread collective, and Persak & Wurmfeld in the design of Blue City. The show also hinted at the sorts of research and public outreach initiatives promised by the RETI Center within its new facility by making room for presentations focused on potential infrastructural improvements in Red Hook’s parks and sewers, as well as a table dedicated to 3D-printed building models by preteen and teenage architects under the tutelage of AE Superlab at the Red Hook Art Project.

A private conference of architects, entrepreneurs, and community organizers followed the opening of the exhibition on November 29. As of this writing, the show at 153 Coffey Street has no set end date, and interested parties can contact reticenterbrooklyn@gmail.com to arrange a visit.