On September 24, friends and neighbors gathered outside the Brooklyn Ice House at 318 Van Brunt Street to commemorate the life of William Robertson, a local musician who died suddently.

On September 24, friends and neighbors gathered outside the Brooklyn Ice House at 318 Van Brunt Street to commemorate the life of William Robertson, a local musician who died suddently.

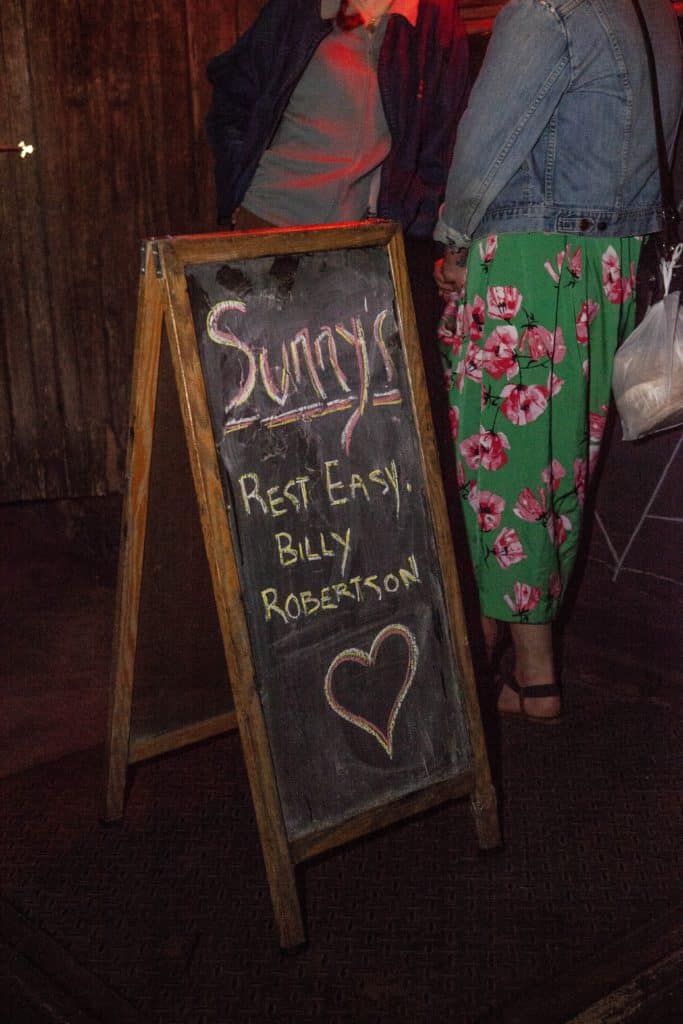

At 7:30 pm, bagpiper Christopher Rodriguez led the crowd of more than 70 past Bene

Coopersmith’s record shop, to Sunny’s Bar on Conover Street, for complimentary Budweisers.

Outside, a chalkboard on the sidewalk read: “Your friends and enemies love you, William!”

After lingering a while, the party – guided by another Scottish dirge – marched to Rocky

Sullivan’s on Beard Street, where they celebrated Robertson’s life by sharing memories over

drinks, a small buffet, and a stack of pies from Mark’s Red Hook Pizza. Several neighborhood

musicians, including Marty McDermott, Jaimie Branch, Kenny Mathieson, Scott Murchison, and

Steve Smithie (better known as “Smitty” or “Stevie from St. Lou”), performed on the bar’s stage,

some playing covers of Robertson’s songs, in front of two of his former bandmates.

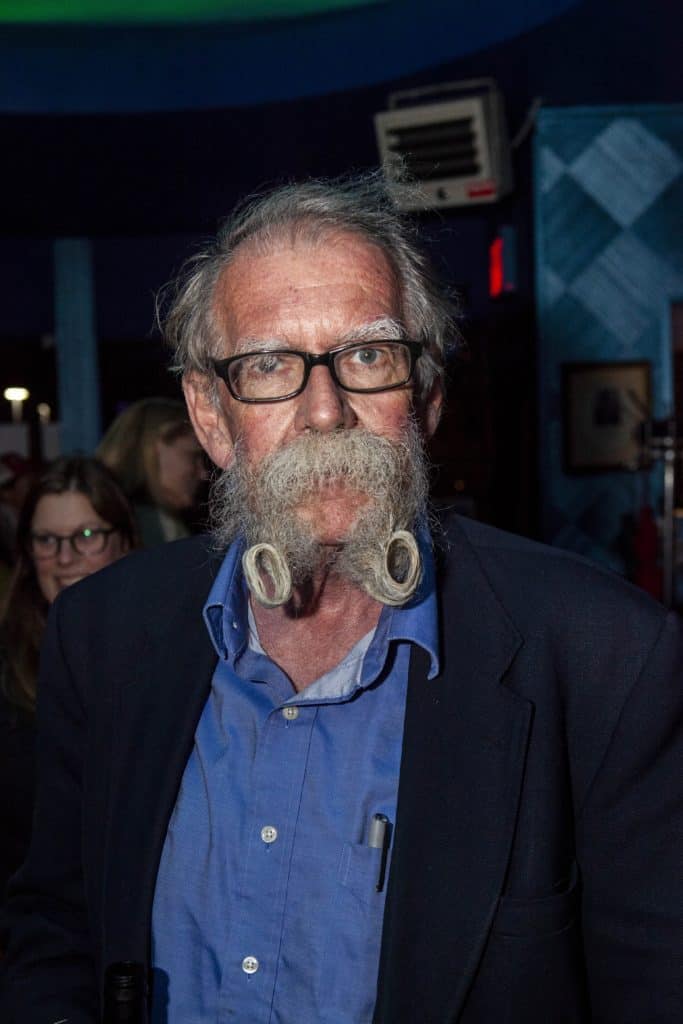

As a young man in the New York post-punk scene, Robertson, known then as Billy, made

a name for himself first with the band Model Citizens (whose sole record, “Shift the Blame,” was

produced by John Cale of the Velvet Underground) and then, most famously, as the lead singer

of Polyrock, an art rock group whose self-titled debut LP – for which Robertson wrote or co-

wrote all 11 tracks – was released by RCA in 1980. The minimalist composer Philip Glass

produced the album and played the keyboard and piano. “I see him as another member of the

band,” Robertson said of Glass in a 1981 interview. John Picarella, a critic for the Village Voice,

compared Polyrock’s avant-garde sound to the geometric paintings of Piet Mondrian.

The following year, Glass produced another album for Polyrock, “Changing Hearts,” and

Robertson took over production duties for an EP, “Above the Fruited Plains,” in 1982, just

before the group’s breakup. A cassette compilation of previously unreleased tracks arrived in

1986. In the liner notes, Robertson wrote, “If there was anything Polyrock set out to do, it was to abandon R&B and traditional rock influences and embrace the likes of Philip Glass and Brian Eno.” He subsequently formed the band Nine Ways to Sunday, whose lone album came out in 1990, and continued to work as a professional songwriter thereafter.

At Rocky’s, Beth Irvin observed that Robertson “had incredible talent, which often

comes with incredible self-questioning and burden.” But “he was a really lovely guy that I liked

to talk to and hang out with, and he always had interesting thoughts about things, and he was

artistically inspired in a million directions.”

In 2014, Robertson appeared in a Star-Revue theater review of “Up for Anything,” a

comedy by Marc Spitz that ran for four sold-out performances at the Jalopy Theatre. “William

Robertson, who many of us know from chatting outside of Bait and Tackle, is an unexpected hit

as a misanthropic piano teacher. He is a composer and claims to have never acted before,” wrote

Kimberly G. Price.

In fact, Robertson lived in an apartment above Bait & Tackle, the Van Brunt Street bar

that shut down in January, and a significant portion of the mourners on the evening of September

24 noted that that was where they’d first met him.

According to Anthony Fatato, Robertson was “a generous man with his time and

creativity.” Jaq Andre described him as “very genuine, very real,” which also made him “hard to

get along with sometimes. He was easy to be upset with, but it never lasted for long.”

Tyler Miller – who believed Robertson was “an amazing character” who “made people

feel like they were part of the same community” and “appreciated you for who you were” –

elaborated by relating an occasion when Robertson attempted to compliment him: “He said, ‘One

thing I like about you is that you always have a smile.’ And then he also said, ‘Maybe you’re just

simple.’ He would pull you in by insulting you a little bit.”

Helped local band

Andrew Amendola recalled how Robertson helped out his own metal band after he lost

his bass player just before a series of shows: “The reason I went to him was because I knew how

proficient he was with music, and there was nobody else who would be able to learn the songs in

such a short period of time, without proper rehearsal. He came in and listened to us do the set

one time – he had that skillset to be able to listen to the song and get 80 percent of the gist of it.”

Amid the rush leading up to the first show, Amendola forgot to warn Robertson about the intense

fog machines that his band liked to use. “When we were on stage and I knew the fog was going

to hit, I looked to the left and he was right underneath, and it caught him in the face and blew

him back. He came up to me after the show and said, ‘Mate, you could have told me about the

machines.’ He got through it like a professional. It was a great couple of shows.”

Robertson had been especially active musically in Red Hook this year, with a regular

Thursday night jam session at the Record Shop. Emily Craven, who wandered in one night after

dinner at Fort Defiance to find Robertson on guitar and the actor Michael Cera playing the

drums, called it “the most live scene I’ve ever seen.” In the view of fellow musician Gibby

Haynes, Robertson’s style had over the years become “more organic, more singer-songwriter-y,

which I think is what every electronic-style musician comes back to.”

Haynes happened to encounter Robertson shortly before his death after a late Friday

night. At 2:30 a.m., “I was in front of my house, and he came zigzagging up the block, and he

said, ‘Come with us down to the pier – we’re gonna go for a swim!’ And I said, ‘Dude, whatever

you do, stay out of the water.’ The next morning, at seven o’clock, I was in front of his

apartment waiting for a coffee shop to open up, and I saw the emergency vehicles, and when you

see emergency vehicles and all the attendants are walking really slowly . . .”

Haynes trailed off, and then added, “He was just a sweet curmudgeon. When I told him

not to endanger himself, he paused a second and said, ‘Thanks, man.’”

Last June, Robertson acknowledged his troubles in a Facebook post. “I’ve fallen into

many of dark places especially lately mostly due to over drinking,” he shared. “I say choose life

drink much less I say choose life.”