During much of the 19th century, most of Red Hook east of Dwight Street was basically underwater. Even while they built up the criss-crossing grid of streets, the lots between graded roads were dominated by marshes and tidal pools. To fill it in, the owner, William Beard, leased it out to “carters,” who would pick up people’s garbage and the ashes from furnaces, stoves and fireplaces, and dump them in the low lots between streets. It was swampy, full of garbage, and could not be developed until it was higher and dryer.This kept the value of the land very low.

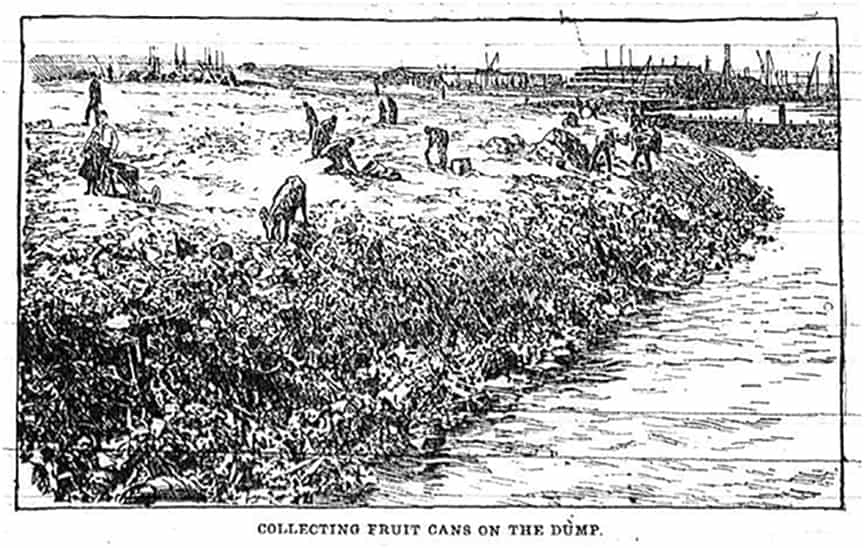

However, the very thing that made it unappealing to developers, made it very appealing to another population. They were junkmen and their families, and by the end of the 1860s, their shantytowns came to define Red Hook’s landscape east of Dwight Street. Junkmen made a living off the dumps, salvaging and reselling anything that had a value. Some focused on particular kinds of junk. Rag collectors sold their finds by the pound to paper makers. Bonemen had similar arrangements with soap factories, glue manufacturers, and rendering plants. Some would melt down tin cans in order to separate the solder from the iron, both of which could be sold to local foundries.\

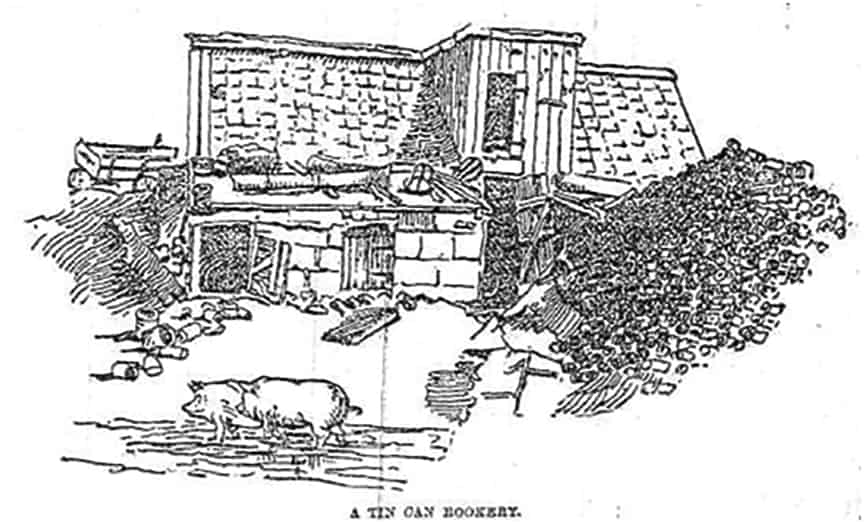

The junkmen made their homes right on the dumps, using materials they found there amid the trash or purchased from local lumber yards. In 1857, the shanties were so numerous at the foot of Columbia Street that the area was given its own village name – “Tinkerville” inhabited by about 160 families. By 1862, nearby communities had grown large enough to be given named identities as well: Dutchtown, Texas, and Pig Hollow. In 1865, there were 643 inhabited shanties in the twelfth ward.

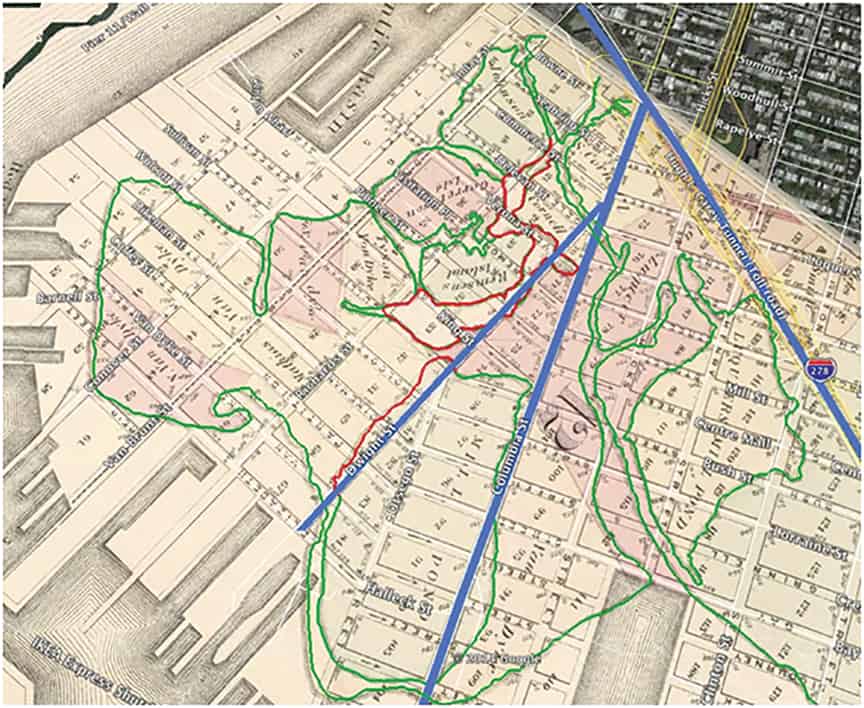

The dividing line between the dumps and the developed area was a tidal creek that ran along the first five or six blocks of Dwight Street. Just after the creek turned away from Dwight Street, it (Dwight Street) ran along the edge of the old Van Dyke mill pond, the western shore of which had been split from the rest of it, giving the appearance of the stream’s continuation over the next several blocks (outlined in red on map).

1874 Brooklyn Farmland overlay map. Composite created by the author.

The residents on the west side of Dwight Street, did not see the shanties as a welcome addition to the neighborhood. Because the dumping grounds and shanties were located almost entirely on the eastern side of Dwight Street (and hence on the eastern side of the “creek”), the people who lived West of Dwight Street on Red Hook Point called the shanty dwellers Creekers. The Creekers, in turn, had a name for those who lived on Red Hook Point – Pointers. It was never recorded why the “Pointers” and the “Creekers” disliked each other, but a number of theories have been put forward.

Some have speculated that the Pointers saw the Creekers as a transient, shadowy, anonymous population, drifting in and out with the tide or change of seasons, because the Erie Basin area was used by canalers to tie up and dock during winter. Canalers owned canal barges and engaged in commerce up and down the Erie Canal. Frequently entire families would live on the boat together. Wherever they found themselves when the canal froze over, making it impossible to conduct their livelihood, they would tie up for winter and live there until the spring thaw. Many of the canalers wintered in Brooklyn, using the Erie Basin because of its protected position at the southern inlet of Gowanus Bay. The breakwater protected them from the winds and waves of storms coming either up or down the coast. Pointers called the canalers “harbor gypsies” and felt they were fly by night out-of-towners who didn’t belong in their community.

Another supposition is that Pointers may have simply been embarrassed of being associated with these strange, uncivilized, garbage dump dwellers. New York newspapers lumped all of Red Hook in together. In 1859, The Tribune called Red Hook the “fag end of a forgotten creation – a ruined town gone to seed, a dilapidated, out-of-the-way, forsaken, forgotten, benighted district of sin and misery, good for nothing under heaven” and claimed that the population was five parts adults, fifty-five parts children, and the remaining forty per cent about equally divided between goats, pigs and dogs.

There may also have been a hint of jealousy in the Pointers’ derision of the Creekers. While the shanty dwellers did live in apparent filth, they had their own homes, were their own masters and had room to move around. Most Pointers were crammed into tenements that could easily match any of their more famous Manhattan counterparts for crowding, filth, or poor ventilation. Of the 57 dwellings listed on Church (now West 9th), Garnet, Center, and Bush Streets in the 100th Electoral District in the census of 1880, only three of them housed more than one family. That’s 60 families in 57 dwellings, all of which were located in the Erie Basin section. Compare this number with the first 57 dwellings listed in the 97th Electoral District, situated on Conover and Partition (now Coffey) Streets, on “the Point” that same year. Those 57 dwellings contained 179 families, sometimes with as many as 7 families and up to 30 people in a single building.

This feud however, was largely a cold war. Pointers tended to stay on their side of Dwight Street, and Creekers on theirs. There was a tension between them though, that usually manifested itself in schoolyard fights between children from either side. Large groups of boys, approximately age 8 to 13 would wage war on each other, throwing rocks and other projectiles, usually over the small piece of marsh that was a kind of no-man’s land between the two group’s turfs. So heavy did the battles become, it was once reported that between 300 and 400 children had been engaged in a single fight, resulting in the arrests of 30 to 60 boys.

By the 1920s, the Pointer/Creeker feud had become a thing of nostalgic storytelling for those boys, now grown up, who once pelted each other with stones. The Creek was gone and nearly all of Red Hook, east and west of Dwight Street had been filled in. Most of the shanties had been swept away with the waves of progress and those few that remained had been converted into more permanent domiciles.

Whatever differences the Pointers and Creekers had perceived of each other during those years of animosity were probably in fact just that – perceptions. The truth was that they had a whole lot more in common than they realized. The problems that were caused by the garbage dumps and smoke-spewing factories affected everyone in the neighborhood. Focusing on their differences prevented them from being able to work together toward goals that would have benefited both communities. Regardless of what side of Dwight Street they were on, they all lived in the same Red Hook.

One Comment

Good story. Historically interesting. J