With rents increasing and condos popping up like mushrooms all around us, Red Hook seems to be changing more and more rapidly. It probably feels this way because we have become accustomed to the landscape around us, the neighborhood that we know and love. But Red Hook has always been susceptible to change, and just as decisions and events are now influencing what the neighborhood will look like in the future, those that shaped it as we know it today were just as flexible and malleable, and anything but predetermined.

Ground broke for the construction of the Red Hook Houses on July 17, 1938, and the first residents moved into their new homes less than one year later. This was one of the earliest public housing projects in New York City, the New York City Housing Authority having only been established in 1934. However, even before NYCHA came into existence, Red Hook had been the suggested location for a public housing community proposed by Louis H. Pink, a member of the New York State Housing Board. Pink’s plan never came to fruition. But if it had, Red Hook would look much different today.

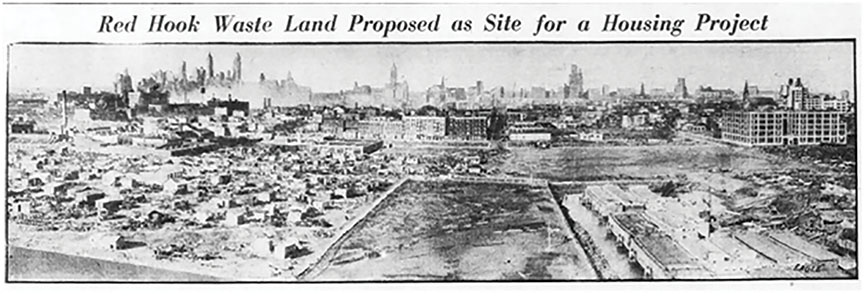

In February of 1933, Pink wrote an op-ed piece for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, pointing out that there was a 40-acre tract of land in the southern part of Red Hook that could easily be developed into a modern public housing neighborhood.

The parcel Pink was referring to had been purchased by the city between 1913 and 1918 with the plans of creating a railroad depot that would act as a linkage between the various ports of manufacture and storage from Bay Ridge to the Wallabout.

Railroad depot never built

By 1933, the land wasn’t really vacant. Over the years, it had become the site of an unofficial dumping ground, referred to by locals as Tin Can Mountain. With the onset of the Great Depression, it also became a Hooverville, similar to those popping up all over the country at that time, with about 400 squatters in residence. The press referred to the area with terms such as “wasteland,” “auto morgue,” and “hobo jungle.”

Pink thought of the area somewhat differently. Where some saw nothing but corrugated shacks and rusted out cars, Pink saw fountains, parks, and brownstones.

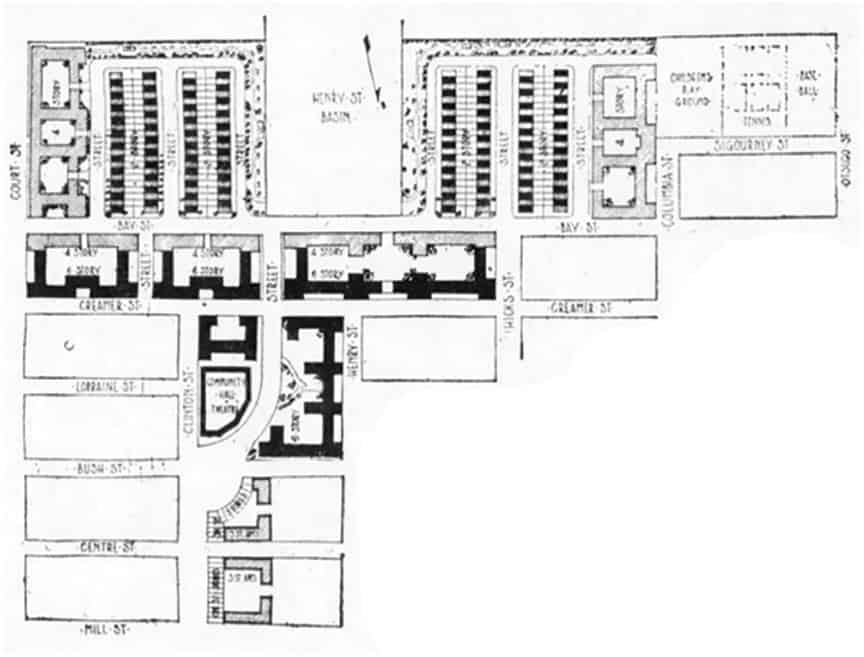

Rather than the cookie cutter style of most public housing projects, Pink envisioned a more diverse style of architecture, mixing one and two family homes with apartment buildings of varying heights – some as high as nine or twelve stories and others as small as three or four. In the middle of it all would have been a public square and Main Street-type area with stores, a movie theater and a meeting hall/recreation center. Topping off his utopic vision was a fountain and sculpture garden, with statues made by local artists.

Of course, this was all just an unofficial suggestion before the New York City Housing Authority was even created. It must have hit a nerve however, because one year later when NYCHA was established, Red Hook was one of the first spots on Chairman Langdon Post’s list of possible development sites. At the same moment, however, New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses was also eyeballing Tin Can Mountain for a large scale recreation area.

An interesting tug of war ensued, but in the end, Moses won the battle for the land. The shanties were destroyed, the 400 residents told to find homes elsewhere, and in 1936 the Red Hook Pool and Ballfields opened on the very spot Pink had suggested for his unique housing community. While Post set his sights elsewhere in the city, a strip of the land was saved and set aside for the possibility of future use as a public housing site. Two years later, it would become a part of the location of the Red Hook Houses.

Had Pink’s initial proposal been put into action as it was first presented, the Red Hook we know today would be a very different place to walk around. Of course, if it had been put into action, we would probably now be wondering what Red Hook would have been like if Robert Moses had been able to put in those proposed ballfields and public pool.

Our modern landscape is the cumulative result of many people’s past actions and we live with the legacy of decisions made by men and women who have long since passed from our midst. As Red Hook continues to transform and evolve with growing rapidity, let us try to consider what our legacy will be and how our actions will be reflected in the neighborhood, the city, and the world we will inevitably leave behind.