In December, two public schools in Red Hook, PS 676 and South Brooklyn Community High School (SBCHS), received word that they’d advanced to the second round of the Imagine Schools NYC competition. Out of 231 applicants, 91 survived the first cut.

Imagine Schools NYC represents a public-private partnership between the New York City Department of Education (DOE) and two philanthropic funders: the Robin Hood Foundation, a Wall Street-backed charity with $431 million in total assets; and the XQ Institute, a school reform organization that operates as an arm of the “impact investment” firm Emerson Collective, founded in Palo Alto by Laurene Powell Jobs, the Apple co-founder’s widow. Together, XQ and Robin Hood will gift $16 million to the DOE, which will match the contribution, to seed 20 new schools and 20 “reimagined” schools in New York City.

Based on test scores and other factors such as attendance, New York State flagged both PS 676 and SBCHS as underperforming schools (or “Comprehensive Support and Improvement Schools,” requiring intervention) in 2019. Both serve primarily low-income, black and brown students.

XQ’s instruction manual encourages applicants to “turn school design on its head” and to “consider how the world is changing for young people, and how education can change to prepare them better for life.” In October, the DOE opened a call for submissions: any public school could pitch a redesign plan, and any individual or group of individuals – irrespective of qualifications – could send in a proposal for a new school.

“The whole concept behind Imagine Schools is to allow a school, in a collaborative way, to come up with a big idea, and this big idea is an idea that is something we can make a reality,” Priscilla Figueroa, the principal of PS 676, said. “It allows you this opportunity to think outside the box and not worry about funding or money. If you could think of a place where students would learn and be happy while learning, what would that place be like?”

The one-time donation by XQ and Robin Hood will amount to 0.0625 percent of the DOE’s annual budget of $25.6 billion (which comes to $13.7 million per school), and the program’s grants for individual schools will top out at $500,000. That sum, however, would mean a lot to PS 676.

Going out to sea

Last year, a partnership with the nonprofit PortSide New York at Atlantic Basin helped PS 676 introduced a “maritime STEAM” focus into its curriculum, and Figueroa now hopes to use the Imagine Schools initiative to facilitate its transformation into a full-fledged “harbor school” – a model used in different ways by the New York Harbor School on Governors Island, the Harbor View School on Staten Island, and SUNY Maritime College in Throggs Neck.

Since taking over in 2017, Figueroa has reconfigured PS 676’s relationship to its surrounding neighborhood, assessing Red Hook not as a hostile urban wasteland but as a resource-rich community whose proximity to water could, if properly utilized, offer a major opportunity to students for play, study, and exploration. “There are many advantages to living in Red Hook,” she noted.

Another significant resource is the abundance of community-based organizations and nonprofits in the area. Among its core principles, XQ emphasizes “powerful partnerships – with community and cultural institutions, business and industry, higher education, nonprofit organizations, and health and service providers – that provide support, real-world experiences, and networking opportunities for students.”

For its Imagine Schools proposal, PS 676 has teamed up with the Billion Oyster Project, Redemption Red Hook, the Red Hook Initiative, and others. SBCHS’s team includes Hook Arts Media, the Red Hook Community Justice Center, and Kingsborough Community College.

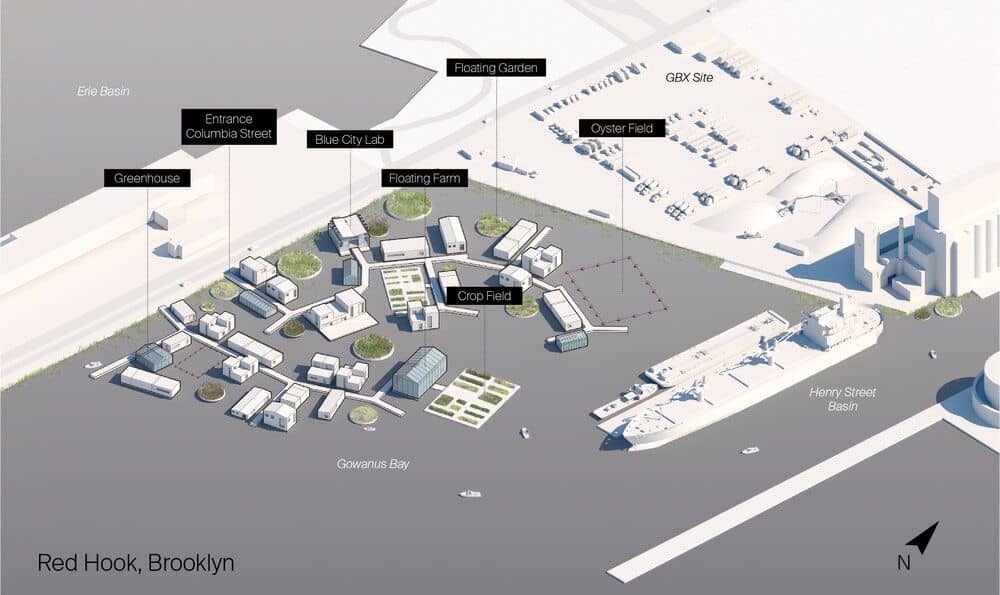

The RETI Center, which advocates for climate-focused economic development in Brooklyn, plays an especially important role in both schools’ efforts. Its ambitious “Blue City” project – a proposed floating village just beyond the shoreline of the Gowanus Bay Terminal – could someday provide a new waterborne campus for PS 676. Meanwhile, the RETI Center’s expertise in green workforce training has helped guide SBCHS’s Imagine Schools vision, which centers a theme of resiliency.

Transforming a school to transform a neighborhood

SBCHS, as a “transfer high school” for “over-age and under-accredited students,” already employs a novel education model. The DOE operates the school in conjunction with a nonprofit, Good Shepherd Services. “The Department of Ed is bringing all their instructional knowledge, and what Good Shepherd brings is deep connections in youth development and community resources,” Good Shepherd Services director Rachel Forsyth explained.

“We exist to serve students who have had difficulty in their previous schools for many, many reasons. When the Imagine Schools opportunity came along, we’d already been talking about how to push to the next level of thinking for our school,” she recounted. Conversations with alumni, who’ve since joined her redesign team, led Forsyth to conclude that SBCHS had to do more “to prepare its students for their next steps” after graduation.

At the same time, Forsyth had become aware that Red Hook itself also needed to prepare for an uncertain future in the age of climate change. To survive rising sea levels, the neighborhood would require a transformation of its built environment. In Forsyth’s view, this process could serve as a source of employment – “Green New Deal jobs” – for its young residents.

“We survived Hurricane Sandy and saw a lot of people from the outside come in here and try to talk to the neighborhood about how to deal with the fact that we’re in a floodplain and this is going to happen again,” she recalled. “When we learned about RETI being in the neighborhood, one of the thoughts was that we want our young people to be able to be trained and have the skills to be leaders in their community.”

Once SBCHS and PS 676 passed Imagine Schools’ initial screening, administrators began a three-month in-depth design process, attending workshops alongside parents, students, and partners. The applicant field will shrink again at the end of March. In late June, the winners will emerge and, after the summer, will use grants to implement their redesign plans, initially as pilot programs.

Forsyth acknowledged that the schedule has been “very fast,” with lots of deadlines. Both schools have devoted a great deal of resources to the challenge without any guarantee of reward.

The public weighs in

Not all of New York City’s educators approve of the Imagine Schools initiative. XQ and Robin Hood have both funded charter schools, whose opponents in New York have included groups like the Alliance for Quality Education and the New York Collective of Radical Educators, as well as Mayor de Blasio. The DOE will own and operate the new and redesigned schools yielded by Imagine Schools, but by giving philanthropists some say over the shape of these institutions, the program introduces a vector of private influence into otherwise straightforwardly public education.

The DOE hosted an Imagine Schools information session in Bay Ridge in February. In the audience, teachers and parents expressed their concerns.

“What’s the catch?” one man wondered. “Oftentimes, in public-private partnerships, it’s the public that ends up doing all the work, and the philanthropy wants something in return. In some cases, it’s more standardized testing or some kind of accountability practice.” DOE representatives quickly batted away the accusation.

A woman castigated the DOE for prioritizing “innovation” in select schools when it had not yet succeeded in providing “the very basic bare necessities” for all students. She spoke of the hot, overcrowded classroom where her daughter struggled to learn.

Another attendee observed that, while Imagine Schools advocated for forward-thinking methods (with a particular emphasis on culturally responsive pedagogy), it did so for the purpose of meeting a typical, uniform set of standards: “Overall, the push is to create a 21st-century, technologically literate citizenry, because that’s where the job market is.” It might be easy enough in “homogeneous” Finland, he said, to convince everyone to buy into the same academic goals, but it would be difficult to honor the diversity of New York without acknowledging that different students might seek different outcomes in their education.

At SBCHS, Forsyth judged the Imagine Schools initiative differently. “I don’t think they’re being prescriptive about what a school should look like. It’s more like, forget everything you know about what school is supposed to be, and what would make the most sense if you could recreate it?” she described.

While Forsyth and Figueroa credited Imagine Schools for helping to refine their plans for SBCHS and PS 676, the substance of their visions predate the initiative. Imagine Schools has offered the possibility of a means to achieve those visions, but PS 676, for instance, had begun to forge its new community partnerships “even before applying for Imagine Schools,” Figueroa clarified. “There are different ways to make your dream come true, even if you’re not part of the Imagine process.” She pointed out that, without winning a contest, PS 676 had managed recently to open a robotics laboratory (dubbed a “STEAM Room”) and an aquarium.

“It definitely would be helpful to have the funding,” Forsyth added. “If we didn’t get it, I feel like we’ll still push ourselves to do this.”

For her, “resiliency” is more than an environmentalist buzzword – it’s a part of SBCHS students’ lives. “There’s a deep piece of this that’s also about your interpersonal resilience. Our students found their way to [SBCHS] because they have a lot of strengths and they’re committed to their own development and growth, and we need to build off what brought them here.”

In Forsyth’s view, the Imagine Schools project to find new ways to usher young people from all walks of life into the dynamic and demanding economy of the future can align with SBCHS’s longstanding commitment to the safety and emotional well-being of its students. Her redesign team has relied on the voices of pupils and alumni to identify those intersections.

“Students are talking about basic needs,” she reported. “We need a safe place to live. We need regular food. Some students don’t eat on a regular basis when they’re at home. Some students don’t have access to laundry. Those aren’t fancy, sexy STEM or STEAM career things – those are some basics that also will be at play in our application, because we can’t get to that other stuff if we’re not taking care of the fundamental needs of human beings.”