You’re reading this right now, so you likely recognize the importance of the Red Hook Star-Revue. Do you know how lucky we are to have a neighborhood newspaper? It reports on local events, holds our elected officials accountable to their campaign promises and supports our neighborhood businesses through advertising. Who else looks out for us like this?

This paper is reminiscent of one of the all-time greats, The Village Voice. That might have been the place where you found your first apartment or the reason you moved to New York in the first place.

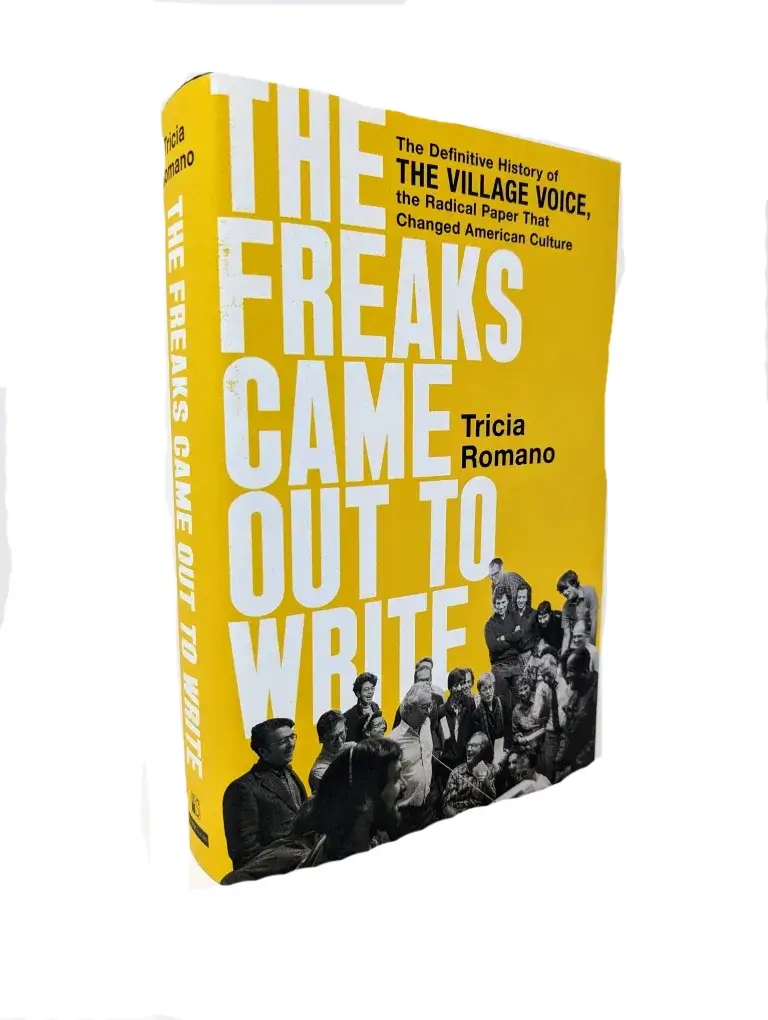

If you think you’re too young to remember it, know that The Voice still exists online and occasionally in print. “The Freaks Came Out to Write: The Definitive History of The Village Voice, the Radical Paper That Changed American Culture” is an oral history that relives the paper’s glory days. Author Tricia Romano (a former Voice writer) interviewed over 200 people connected to the paper to piece together its fascinating history. She does so brilliantly. The interviews are candid, passionate and insightful. Gossip and grievances make “Freaks” a big, juicy page-turner.

Dan Wolf (editor-in-chief), Ed Fancher (publisher) and Norman Mailer (writer) started The Voice as an independent community newspaper in 1955. It was devoted to downtown (below 14th Street), offering news, social commentary and ads for jobs, apartments and sex (among other things). It soon gained a reputation for taking seriously topics marginalized by mainstream media.

The Voice called out crummy landlords and corrupt politicians. It covered Black rights, women’s rights and gay rights. It also elevated cultural coverage, previously a low priority for mainstream papers, breaking stories on modern dance, experimental theater, independent film, contemporary art and rock, rap and hip-hop.

Wolf recalls his vision for the paper as “a living, breathing attempt to demolish the notion that one needs to be a professional to accomplish something…It was a philosophical position.” Instead of hiring “experts,” they recruited people who lived what their byline was about: people who weren’t necessarily writers but had urgent stories to tell. These people learned to write on the job.

This approach helped spawn new journalism, emphasizing storytelling, an exploration of social issues and the writer’s personal response. Readers not only learned about the world but also gained insight into the person writing about it.

“Freaks” celebrates The Voice’s influence while uncovering rivalries, hostilities and inequities. Just like everywhere else, women, gays and people of color bear the brunt of it. The rise of the internet, particularly Craigslist (which ate into classified ad sales), hastened the paper’s demise.

Romano’s collaged portrait captures what made the Voice great—it wasn’t about one voice with an agenda but about different voices, each with a unique perspective. Romano provides a brief breakdown of some of them in a 15-page cast of characters. Nevertheless, some of your favorites might not have made the cut (shout-out to Toni Schlesinger and her Shelter column!).

The Voice helped reshape our collective understanding of the world, subsequently transforming that world. Suddenly, there was no longer mainstream media and its alternative. There was only media, a spectrum, consuming everyone’s attention on our digital devices. Romano’s account is bittersweet. It might make you long for a more analog world.

Like the Voice before it, the Star-Revue fosters a sense of community among its readers. It reflects the issues that matter and provides a platform for writers (like me) to find and cultivate their voices.

Review by Michael Quinn