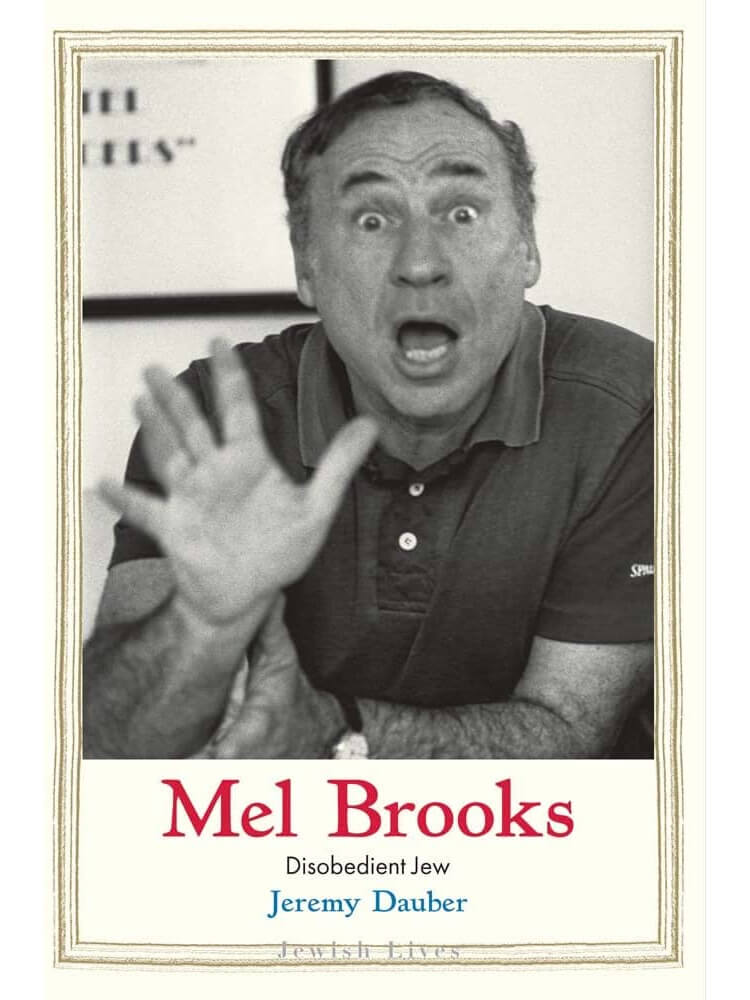

Review of Mel Brooks: Disobedient Jew, by Jeremy Dauber

Review by Michael Quinn

Born in Brooklyn in 1926, Melvin Kaminsky was the youngest of four boys whom the fatherless family doted on. “Until I was six, my feet didn’t touch the ground,” he remembers. He was quick with a smile, a natural mimic, and good at making people laugh. He honed his comedy chops on the stoops and streets of his Brownsville neighborhood.

As a teenager in Brighton Beach, he took up the drums, allegedly using a shortened version of his mother’s maiden name, Brookman, as his stage name because that’s what fit on the bass drum. Too young to enlist in World War II, he headed to the Catskills’ famed Borscht Belt for a summer gig, providing rim shots for the comedians. One night he did an act of his own. He was an instant hit.

“Mel Brooks: Disobedient Jew,” by Jeremy Dauber, a professor of Jewish literature and American studies at Colombia University, is not only a biography of the comedy genius but a smart, snappy, and insightful investigation into how Brooks can take any subject and “make it funny by making it Jewish.” In Brooks’ world, someone doesn’t just eat a fish. They eat a herring—in a Western.

By now, we’re so used to this kind of bonkers comedy it’s easy to overlook how much of a trailblazer the 96-year-old is. Neither antisemitism nor social norms can get him to be anything other than himself. He is always sincere, and he is always irreverent. (For example, he always referred to his movie star wife by both first and last name, Anne Bancroft.) Like the Trojan Horse of comedy, Brooks presents himself as an innocuous gift, worms his way into an impenetrable room, and launches a no-holds-barred attack from the inside, leaving his victims dying with laughter.

His goofy demeanor is completely disarming. He advertises himself as the bullseye when really, he is the one firing the shots. After all, how does comedy work? Someone observes something, captures what makes it unique, then turns it on its ear—you might have only been half-listening, but suddenly you burst out laughing. It’s like your body gets the joke before your mind does. Only later do you realize that the joke might have been made at your expense. By then, Brooks has homed in on someone new.

An early target was comedian Sid Caesar, whom Brooks worshipped and relentlessly perused. Brooks had a retort for each of Caesar’s rebuffs, which eventually wore him down and finally won him over. Brooks then charmed his way into the writers’ room, “popping Raisinets…pitching…ideas at a mile a minute.” While working on a television variety show, he befriended Carl Reiner. Together they developed Brooks’ most famous improvisational character, the 2,000-Year-Old Man, who recalls witnessing some of history’s most important events—with a Yiddish accent.

Dauber helps us see how the roots of Brooks’ comedy can be traced to vaudeville and burlesque comedy traditions. He helps us hear how Brooks has a musician’s ear for timing, perfectly punctuating his material with well-placed gags and zingers. And he helps us truly appreciate Brooks’ gift for parody: lampooning something familiar and doing something unexpected with it. As he points out, Brooks’ most successful films from the 1970s all follow the same winning formula: “The Producers” (spoof on show business), “Young Frankenstein” (spoof on Universal horror films), “Blazing Saddles” (spoof on Westerns). Brooks’ stamp on things is unmistakable. He brought his experience of being an American Jew to the mainstream—and made it mainstream. His humor is oppositional. It’s bold. It’s outsider. It’s fearless. And as Dauber points out, what’s most winning about it is that it “shines with love and affection for the community it mocks.”