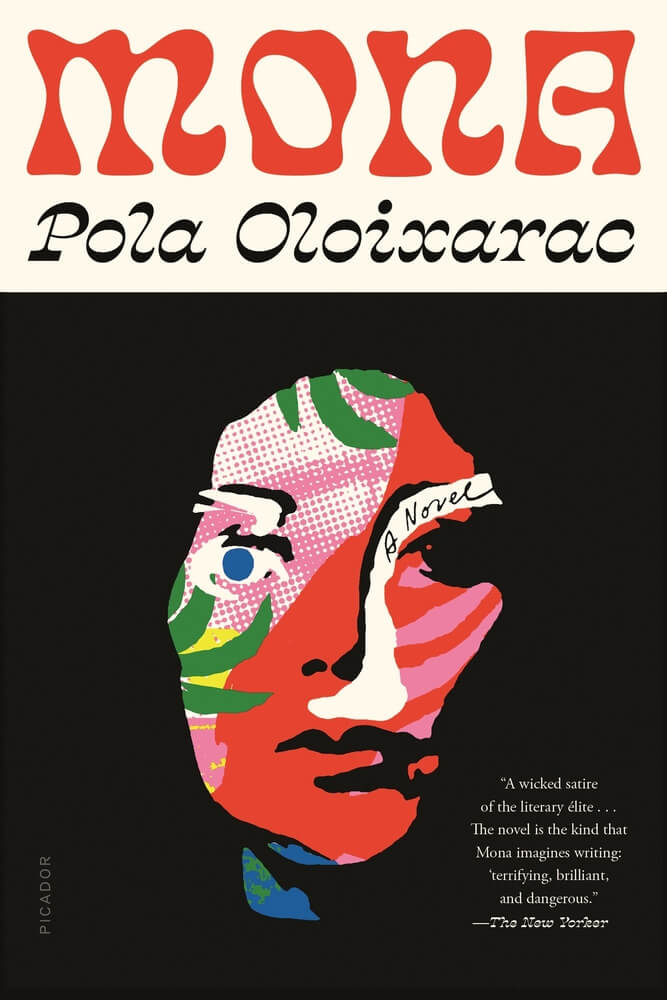

Review of Mona by Pola Oloixarac, Translated from the Spanish by Adam Morris

Review by Michael Quinn

Waking up on a Palo Alto train station platform, covered in blood, with no memory of what happened or how she got there, Mona, the title character of the third novel by Argentinian writer Pola Oloixarac (translated from the Spanish by Adam Morris), outpaces self-discovery by running away. Rather than try to sort out what’s happened to her, Mona, a gifted Peruvian writer, spontaneously accepts an invitation to attend a literary conference in Sweden, abandoning her doctoral work at Stanford along with text messages from a persistent, neglected lover. Before heading to the airport, Mona vapes, pops a Valium, and ties a scarf around her neck to cover the bruises.

So much for the great escape: As the old saying goes, wherever you go, there you are. While Sweden is bucolic and beautiful, Mona skulks around in her filthy prescription sunglasses and a trench coat, looking down on her fellow writers and eavesdropping on their conversations like an unhappy spy. Although her debut novel is up for Europe’s most prestigious literary award, Mona seems less like a promising ingénue than a bitter has-been, full of disdain for the literary world she inhabits. “The phony solidarity of having a ‘Latin’ culture in common with other writers was something that had always repulsed her,” Oloixarac writes. Yet Mona is aware of both the trappings and advantages of a persona; she describes herself (to herself) as “playing the part of an overeducated Latina adrift in Trump’s America.”

Though she doesn’t recognize it, Mona is not so different from the other 12 award finalists, who hail from countries all over the world, and who vacillate between feeling insignificant and like rock stars. Despite having opportunities to bond, Mona remains at a stoned remove, observant and privately critical, while the group attends panels, compares publishers, and gripes about things like TED Talks (“‘Everyone just goes around saying the same thing. Exactly the same thing!,’” one kvetches). An Iranian writer, having convinced himself he has no chance to win the big prize, uses his opportunity in front of the captive audience to make a pro-Muslim speech— “‘Europe is pregnant! Pregnant with our children!’”—much to Mona’s amusement. It’s not so much his ideas that excite her, but the disturbance he creates. Mona perks up in chaotic situations where others are made as unhappy as she is.

At heart, Mona’s an escapist: “it was the sensation of losing consciousness that Mona associated with pleasure.” Alone in her hotel room, she gets stoned, peels the Band-Aid off of her laptop’s camera (she’s paranoid about being spied on), and masturbates with a partner, Franco, on Skype. Rather than Franco, showing off is what turns Mona on. She’s hurt by his inattention—even when she’s the one with her eyes closed: “When she reopened them, Franco was staring intently at something else on his screen, focused on something that wasn’t her.”

Although Mona recognizes herself as “a total nympho for terror,” in her darker moments, alone, she doesn’t know what she’s really afraid of—or why. The bigger problem is, the author doesn’t know, either. Reading Mona is like reading a notebook full of Oloixarac’s undeveloped ideas: a 12-year-old girl who goes missing in Lima; a group of strange men, wondering around Sweden like a wild tribe; a fox with its throat slit, along with another decapitated animal. These all feel like clues but they don’t add up to a satisfying mystery.

Mona’s superiority complex would’ve been narratively satisfying had it been exposed (like in the children’s classic Harriet the Spy, when the 11-year-old would-be writer loses her notebook with harsh criticisms of her classmates, and is then confronted by them when they discover it). But Mona never gets her comeuppance. She doesn’t get much of anything at all. Oloixarac isn’t sure what to do with this prickly, unlikable character she’s created. A tidal wave of magic realism at the novel’s end does them both in. Even when we find out what happened to Mona at the train station, it feels like a cheap play for sympathy—Oloixarac’s, not Mona’s. That Oloixarac would turn Mona into such a paint-by-numbers victim is the biggest mystery of all.

Quinn on Books: Unsolved Mysteries

READ OUR FULL PRINT EDITION

Our Sister Publication

a word from our sponsors!

Latest Media Guide!

Where to find the Star-Revue

How many have visited our site?

Social Media

Most Popular

Big donors taking an interest in our City Council races

Wraptor celebrates the start of spring

Related Posts

Special birthday issue – information for advertisers

Author George Fiala George Fiala has worked in radio, newspapers and direct marketing his whole life, except for when he was a vendor at Shea Stadium, pizza and cheesesteak maker in Lancaster, PA, and an occasional comic book dealer. He studied English and drinking in college, international relations at the New School, and in his spare time plays drums and

PS 15’s ACES program a boon for students with special needs, by Laryn Kuchta

At P.S. 15 Patrick F. Daly in Red Hook, staff are reshaping the way elementary schoolers learn educationally and socially. They’ve put special emphasis on programs for students with intellectual disabilities and students who are learning or want to learn a second language, making sure those students have the same advantages and interactions any other child would. P.S. 15’s ACES

Big donors taking an interest in our City Council races

The New York City Council primary is less than three months away, and as campaigns are picking up steam, so are donations. In districts 38 and 39 in South Brooklyn, Incumbents Alexa Avilés (District 38) and Shahana Hanif (District 39) are being challenged by two moderate Democrats, and as we reported last month, big money is making its way into

Wraptor celebrates the start of spring

Red Hook’s Wraptor Restaurant, located at 358 Columbia St., marked the start of spring on March 30. Despite cool weather in the low 50s, more than 50 people showed up to enjoy the festivities. “We wanted to do something nice for everyone and celebrate the start of the spring so we got the permits to have everyone out in front,”