Review of Invisible Ink by Patrick Modiano, translated from the French by Mark Polizzotti

Review by Michael Quinn

What constitutes a life is not only our experiences, but our feelings about them. Especially as we grow older, our memories play a role here, too. We lean into some, and are unexpectedly overcome by others, triggered by a smell, the name of a long-lost love, or a forgotten song whose refrain suddenly springs to our lips.

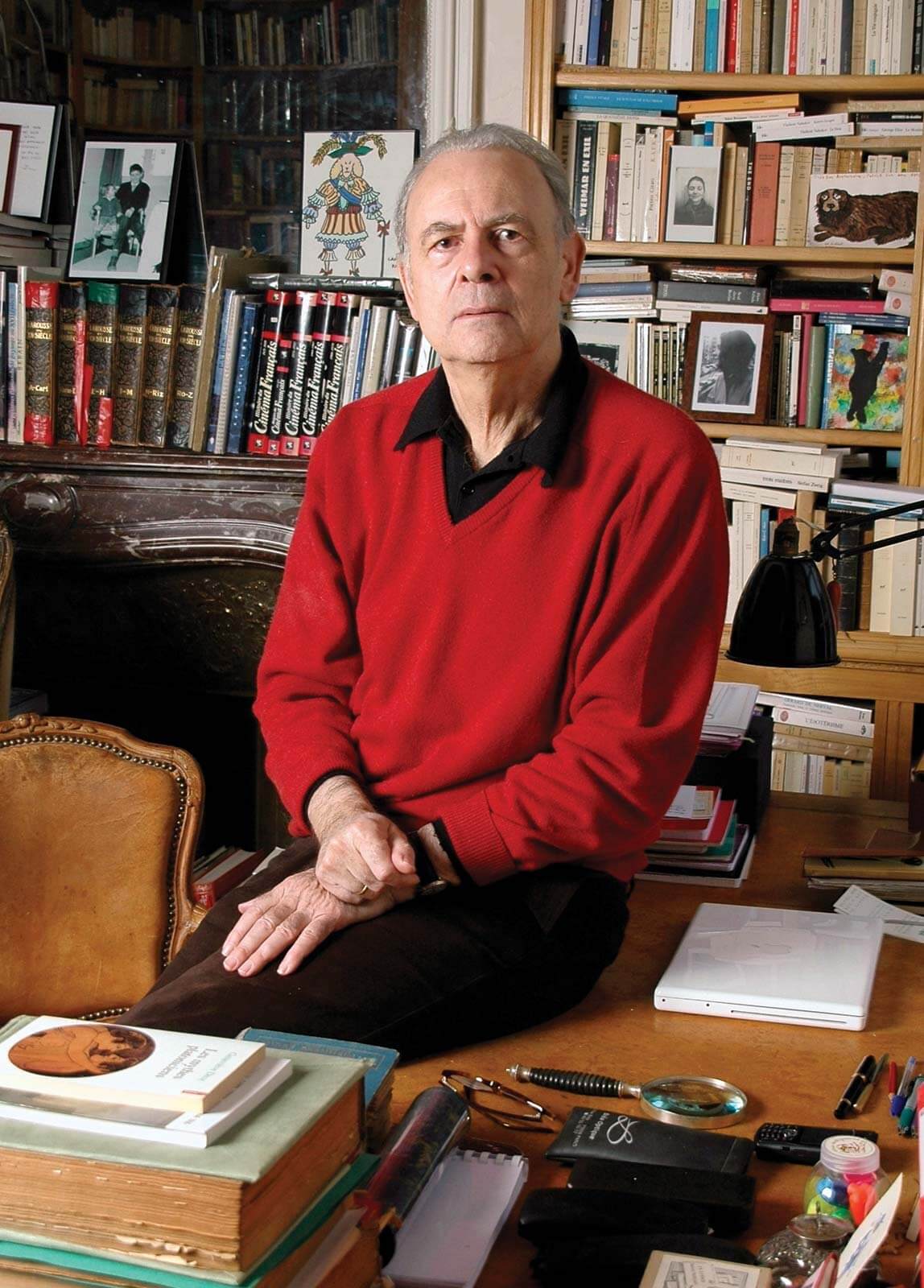

The Nobel Prize-winning French writer Patrick Modiano has written volumes on this subject. His slender, enigmatic novels often involve a missing woman and a man in search of her. The clues the man amasses don’t much help him with his pursuit, yet they seem to lead him into some deeper understanding of himself, if only by his recognition that they mean something to him, although it’s often hard for him to say what, or why.

Are you intrigued or exasperated by this? That reaction will be a good indicator for what you’ll make of Modiano’s latest novel, Invisible Ink, beautifully translated from the French by Mark Polizzotti. All of the familiar Modiano elements are here: the man in pursuit, the missing woman, Paris in the 1960s. But there seems to be a new urgency, as well as bafflement about what it all means (if anything) that I can only guess reflects Modiano’s own grappling with mortality (he’s 75).

The story centers around Jean Eyben, a young man with literary ambitions. On a whim, he takes a job at a shabby detective agency, work that “clashed with my natural shyness.” Given few facts and an illegible photograph, Jean’s first (and only) assignment concerns a missing person, a young woman named Noëlle Lebebvre. The case bears no fruit, but thirty years later, despite having abandoned that line of work, Jean can’t stop thinking about random moments associated with it. He decides to write down the facts as he remembers them, and that’s what constitutes the novel.

At first, Jean sets down a rather straightforward account. He remembers scoping out a café in Noëlle’s old neighborhood. There he meets Gérard Mourade, an aspiring actor, who knew Noëlle, and might have had designs on her husband. Husband? Jean wonders. That wasn’t on the cheat sheet. Jean pretends to be an old friend of Noëlle’s, and convinces Gérard to join his search. They head to Noëlle’s apartment (Gérard has a key), and while Gérard interrogates the neighbors, Jean finds a datebook with Noëlle’s handwriting, which he steals. Many of the entries are empty, but years later, he continues to pour over them, as if he’ll uncover some new information. “‘If I had known…’” begins one abandoned entry.

Jean becomes infatuated with the vanished Noëlle, drawn to the “vagueness and uncertainty” surrounding her. Her absence becomes mixed up with the passage of time and the passing of his youth. “I felt like an amnesiac who has been handed a very detailed route that he has to follow in a place that was once familiar. The name of a village alone might suddenly call up his entire past,” Jean writes.

Fragments of memory seem to be invested with more detail and meaning the farther Jean moves away from them in time. Reflecting on that first conversation with Gérard decades earlier, Jean seems to locate himself in the memory, gradually becoming aware that there were “the shouts of children coming home from the school next door—children who by now would be middle-aged.” It “belonged to an eternal present,” Jean reflects.

The people remain strangers; the moments, fleeting. Yet they constitute the whole of the novel, and the recovered memories seem precious, and potent with meaning. By setting them down, Jean seems to be uncovering some mystery central to himself: “It’s as if all this was already written in invisible ink.”

Like a metaphysical detective novel, Invisible Ink is concerned with memory, time, forgetting, and remembering. Modiano is all about mood. There is no one more masterful at evoking vintage Paris, as if uncorking a bottle right under your nose that triggers the sensory picture of it: rainy days and uneven sidewalks, the sounds of mopeds, a cup being set in its saucer, flat leather shoes striking the pavement. His writing conveys a tremendous depth, and mystery. It demonstrates an obsession with the past, without eulogizing it—it conveys only the constant surprise of it slipping through our fingers. “And sometimes, on waking, or very late at night, the memory of a sentence returns from the past, but you don’t know who whispered it,” Jean writes, yet who is this “you” of whom he speaks? It’s the character Jean writing, yet it’s somehow Modiano I hear. And it’s like he’s addressing the two parts of ourselves: the one to whom things happen, and the one who observes them happening—our first and perhaps only lifelong companion. Modiano’s genius is connected to the way he suggests this deeper meaning of things in a way that forces readers to contend with the subject ourselves.

In the book’s final chapters, a different character takes over the narration. It’s a jarring tonal shift, like a piece of music suddenly played in a new key by a different instrument. Life, Modiano seems to say, is full of these twists. Drawn to mysteries, he demonstrates a constitutional aversion to open-and-shut cases. “I’m afraid that once you have all the answers, your life closes in on you like a trap, with the clank of the keys in a prison cell. Wouldn’t it be better to leave empty lots around you, into which you can escape?” By pressing these kinds of existential questions into our psyches, Invisible Ink leaves its indelible mark.