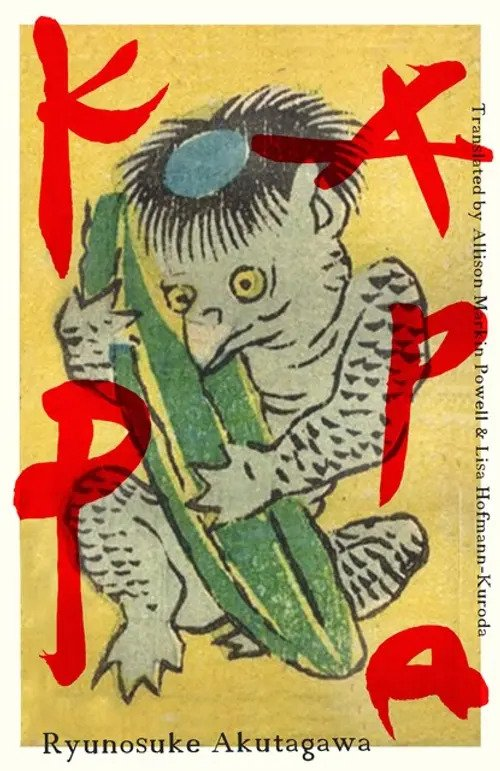

Review of “Kappa,” by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, translated from the Japanese by Allison Markin Powell and Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda

Did you go on any trips this summer? Traveling has many benefits. You might interact with different people, learn a new language, and discover things about another culture’s values. Whenever you go someplace new, you see the world with fresh eyes—and sometimes the home you return to with a critical one.

Patient No. 23 came back from his trip worse for the wear. He is recuperating in a psychiatric hospital outside of Tokyo. An unnamed narrator introduces us to the “youthful-looking madman” and relays his tale in “Kappa” by Ryunosuke Akutagawa (1892–1927). Allison Markin Powell and Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda recently collaborated on a modern translation of one of the prolific short-story writer’s final works.

Before the patient’s mental breakdown, he had set out for a summer mountain hike. He gets disoriented by a rising fog. Suddenly, he catches a glimpse of a strange creature and gives chase, falling into a hole and waking up in a strange (yet strangely familiar) world.

Kappa Land looks a lot like Tokyo, only on a smaller (more miniature) scale; for Kappa, slimy things with chameleon-like skin, beaky mouths, and webbed hands and feet stand only three feet tall. They have pouches in their stomachs and oval-shaped plates on their heads. These creatures view the man as a curiosity, nurse him to health, and invite him to live among them.

At first, the man has a hard time with their language, which sounds like squawking. “Qua,” says one. “Quax, quax!” says another. As the man acclimates, he befriends different Kappas. Each has something different to teach him, whether about love (the females do the pursuing), birth (a Kappa child decides whether or not to be born), or religion (the Kappas practice Lifeism, which is devoted to eating, drinking, and copulating, and takes as its saints such luminaries as the Swedish playwright Strindberg, the German philosopher Nietzsche, and the Russian writer Tolstoy: each a freethinker who clashed with the conventions of his day).

Yet the man struggles to come to terms with the Kappas’ absurdist ways: “They find amusing the things humans take seriously, while at the same time, they take seriously things that we are amused by,” he realizes. For example, regarding politics, Geyl, a factory owner, explains that “every speech is a complete lie. But everyone knows that, so in the end, it might as well be the truth.”

While the man is sometimes horrified by the Kappas’ amorality (workers, displaced by machines, are eaten), what finally pushes him over the edge is the hypocrisy of human culture: pretending to be something that we’re not, pretending to care about things that we don’t. The Kappas don’t love this two-faced existence of ours either. “We Kappas, unlike you—ugh, never mind,” one begins, abandoning the unfavorable comparison.

“Kappa” takes many shots at “modern” society. While written almost 100 years ago, readers will recognize in its pages that we’re still living in the same kind of capitalist world it takes issue with. The novel’s 17 short chapters also tackle such heavy topics as war (including the one between the sexes) and the burdens of family life. Yet “Kappa” is not a straight-up satire. It’s more complex and existential. It’s amusing, disturbing, and strange, haunted by recurring images of bare branches against an empty sky—the ramblings of an alleged madman, imprisoned presumably for his good against his own will for speaking out about obvious truths the collective would prefer to deny.

In his book “Words of a Fool,” the Kappa philosopher Magg advises, “The wisest way to live is to scorn the customs of one’s age while still abiding by them.” Isn’t any philosophy of life a kind of survival guide? Perhaps this was one by which Akutagawa could not abide. Shortly after he wrote this story, he killed himself. “Kappa” could be read as a kind of suicide note. It’s a quick read that will leave a long-lasting impression.