Review of Walking through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black, by Cookie Mueller

Review by Michael Quinn

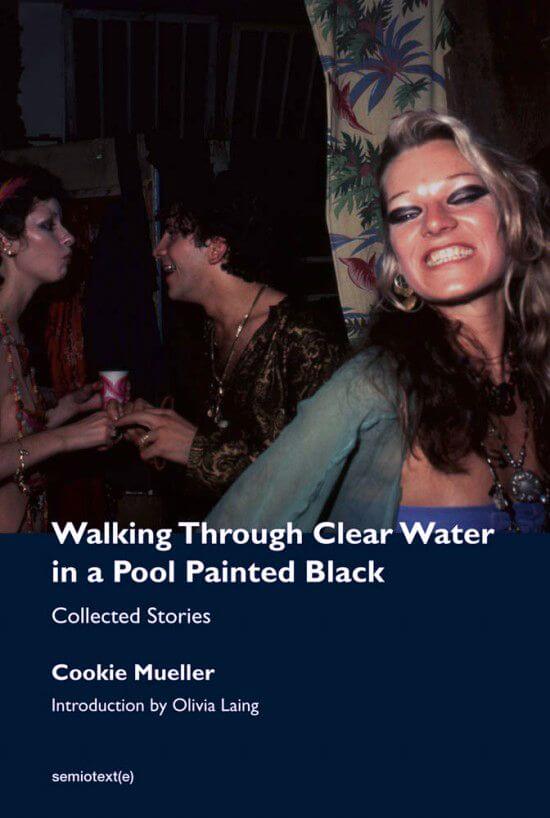

Among the arty crowd, there might be two kinds of people: those who never heard of Cookie Mueller and those who are obsessed with her. She was the ultimate free spirit. Born in Baltimore in 1949, she was, by her own account, an advice columnist, art critic, playwright, actress, drug dealer, go-go dancer, clothing designer, sailor, and “unwed welfare mother,” among many other things. Like many artists of her generation, she lost her life to AIDS. She’s most often remembered as a smoky-eyed, tousled-haired muse to filmmaker John Waters and photographer Nan Goldin. Whatever she did, she did well, because she put her unique stamp on it. But writing seems to be where her most consistent focus lay.

“I started writing when I was six and have never stopped completely,” Mueller confesses in Walking through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black, a new collection edited by Hedi El Kholti, Chris Kraus, and Amy Scholder that rounds up both previously published work and things never before seen. The day before her eleventh birthday, Mueller finished her first magnum opus, a 321-page book on Clara Barton (“the American version of Florence Nightingale”), which she bound in cardboard and shelved in the appropriate section of her local library…never to see it again. Perhaps it’s for this reason she turned to writing short stories, which Mueller calls “novels for people with short attention spans.”

Whether you’re new to the Cookie oeuvre or a longtime fan, Walking through Clear Water holds something for you: either an introduction to this singular talent or a reminder of why she’s so great. Seeing all of her work together in one place doesn’t just give you a sense of her as a writer, but as a person: many of the stories contain autobiographical threads. Hers is a messy, memorable life informed by an absurdist sense of humor, a love of adventure, and a deep attraction to unusual people. Authenticity like Mueller’s is both rare and irresistible.

The work is divided into sections (anchored by where Mueller’s living at any given time) and presented chronologically. Baltimore (1964-1969) draws from Mueller’s formative years. Teenage rebellion is marked by big hair, tight skirts, and high heels. Parents are squares. The typical adult is “an asshole, a rude bigot stomping through life squashing everything to his level.” Romantic relationships, from the get go, are unconventional. While her boyfriend’s hospitalized with hepatitis, Mueller’s narrator spends the night at a friend’s house. The girl begins to feel her up: “‘Just pretend I’m Jack. Just pretend I’m Jack,’” she pleads. After a few weeks, there’s no longer a need to pretend.

Several of the stories recount Mueller’s start as an actress in Waters’ underground films: at a screening, she wins a raffle, scoring dinner with Waters and a screen test. “He was the writer, producer, director, cameraman, soundman, lighting expert, editor, even the distributor,” Mueller explains. In her first role in Multiple Maniacs, Mueller has trouble remembering her lines, but remembers that everyone had to shout, partly because of the crappy sound equipment, partly as “a matter of style.”

She soon develops a close friendship with the actor Divine and other Waters luminaries. They live on welfare and share a poorly-insulated house in Provincetown in the winter, scavenging the dump for things to sell. Come Christmas, they chop down a neighbor’s tree and decorate it with jewelry and fabric flowers fashioned from a cut-up bedspread.

Shortly after her son Max is born, he’s given a part in Pink Flamingos, Waters’ legendary film in which Divine eats dog shit and Mueller is penetrated by a headless chicken. Mueller describes Waters’ films as “cagey, fast-paced…scored with wild music and wilder action.”

Yet Mueller resists this reputation of wildness herself. “I happen to stumble onto wildness,” she explains. “It gets in my path”—this from the woman who accidently burns down a friend’s house in British Columbia.

In her defense, Mueller is a go-with-the-flow Pisces (she was a serious practitioner of astrology), the kind of person who randomly opens an atlas and travels to whatever far flung place her finger happens to land on (this brings her to Rome, and eventually, to her husband, the artist Vittorio Scarpati). Whatever happens—hanging out with Charles Manson’s groupies in San Francisco, attending an LSD party, unwittingly participating in a Satanic ritual, evading multiple rapists—Mueller just seems to roll with it. Only occasionally do her sometimes very dire circumstances seem to hit her with the full weight of hopelessness. With a young son to care for and no place to live, “I didn’t have any money, and there really wasn’t anybody to ask for some to borrow,” she writes. There isn’t a trace of self-pity anywhere in here.

In “Ask Dr. Mueller,” her highly entertaining advice column from the magazine East Village Eye, she answers reader-submitted questions about skin problems, aphrodisiacs, leg cramps, quitting smoking, psychic surgery, and impotence (“I make house calls for this one”) with both levity and a refreshing matter-of-factness. Her reputation as a druggie (pot makes her paranoid so she sticks with “the harder stuff”) seems well-known; elsewhere she calls this assignment her “‘health in the face of drug use’ column.” Mueller advocates for a holistic approach and espouses the benefits of herbal supplements and dietary adjustments—no matter what you’re snorting, shooting, or smoking. Worried about AIDS? “Keep your body very strong and don’t forget your sense of humor,” she advises.

Some of Mueller’s writing seems eerily prescient. In her December/January 1987 “Art and About” column for Details magazine, she reflects on “the age of fleeting media stars”: “Never have so many with so little become so big for a duration of time so short. Never before has such a shiftless bunch of life’s lightweights hewn such formidable nests for themselves in so many people’s minds.” She also touches on deforestation, the destruction of the ozone layer, and “new environmental diseases [which] are a byproduct of toxic water, poisoned air, and nuclear fallout. Mutated viruses, weird pollution, and cell degeneration have finally weakened the race.” Uhm, what year was this written?

In “A Last Letter,” Mueller mourns the friends she’s lost to AIDS, the “kinds of people who lifted the quality of all our lives, their war was against ignorance, the bankruptcy of beauty, and the truancy of culture. They were people who hated and scorned pettiness, intolerance, bigotry, mediocrity, ugliness, and spiritual myopia; the blindness that makes life hollow and insipid was unacceptable. They tried to make us see.” Mueller doesn’t disclose her own condition here or elsewhere; it’s unclear if she ever found words for that experience. But Walking through Clear Water puts her squarely in the company of those she most admired: a fitting legacy for this one-of-a-kind visionary.

Quinn on Books: Stumbling Onto Wildness

READ OUR FULL PRINT EDITION

Our Sister Publication

a word from our sponsors!

Latest Media Guide!

Where to find the Star-Revue

How many have visited our site?

Social Media

Most Popular

Big donors taking an interest in our City Council races

Wraptor celebrates the start of spring

Related Posts

Special birthday issue – information for advertisers

Author George Fiala George Fiala has worked in radio, newspapers and direct marketing his whole life, except for when he was a vendor at Shea Stadium, pizza and cheesesteak maker in Lancaster, PA, and an occasional comic book dealer. He studied English and drinking in college, international relations at the New School, and in his spare time plays drums and

PS 15’s ACES program a boon for students with special needs, by Laryn Kuchta

At P.S. 15 Patrick F. Daly in Red Hook, staff are reshaping the way elementary schoolers learn educationally and socially. They’ve put special emphasis on programs for students with intellectual disabilities and students who are learning or want to learn a second language, making sure those students have the same advantages and interactions any other child would. P.S. 15’s ACES

Big donors taking an interest in our City Council races

The New York City Council primary is less than three months away, and as campaigns are picking up steam, so are donations. In districts 38 and 39 in South Brooklyn, Incumbents Alexa Avilés (District 38) and Shahana Hanif (District 39) are being challenged by two moderate Democrats, and as we reported last month, big money is making its way into

Wraptor celebrates the start of spring

Red Hook’s Wraptor Restaurant, located at 358 Columbia St., marked the start of spring on March 30. Despite cool weather in the low 50s, more than 50 people showed up to enjoy the festivities. “We wanted to do something nice for everyone and celebrate the start of the spring so we got the permits to have everyone out in front,”

One Comment

Pingback: Quinn on Books: Stumbling Onto Wildness - The Headline Update